Professor in Residence, Department of Architecture, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

In this paper, the outcomes of a two-year design research study that investigated the impacts of architectural design on the social, cultural, and economic factors influencing the revitalization of the urban marketplace are summarized. These two case studies in designing and building urban markets in Central Texas — one in the city of Austin, and the other in the town of Bryan — are presented and synthesized. Both cases were initiated, designed, and built by university students in the disciplines of architecture, construction science, and landscape architecture, in collaboration with a cross-disciplinary oversight team of experts, government officials, and professionals. Platforms for engaging in active and dynamic learning experiences in the specific areas of planning, budgeting, and scheduling, as well as design and construction, within the broad field of community development, were provided to the students in both cases.

Marketplaces —also known as market halls, market sheds, or market districts— have always played an important role in the history and development of cities around the world. While these markets are still present in many countries, they have all but disappeared in the United States, a casualty in an urban landscape that has changed quickly to accommodate growing populations and increasing urban density (Brown 2002).

Permanent farmers’ markets, for example, have mostly vanished from the scene as a building typology that carries a strong sense of place-making in towns and cities throughout the United States. Recent social changes, however, have spurred the gradual reappearance of the local marketplace, most commonly in the form of weekly or biweekly farmers’ markets (Johnson, Aussenberg, and Cowan 2014). Unique opportunities for integration, interaction, and expression along diverse urban contexts are provided by this uptrend in urban development across America. Opportunities to revitalize economically struggling communities, change consumer habits, educate consumers on nutrition and other topics, and celebrate diversity in places where it might otherwise be stifled, are inherent in such urban markets, which also provide a basis for improving public health, incubating small businesses, and promoting food safety.

Permanent markets existed long before the invention of the lightweight, collapsible tent that is quickly assembled over the bed of a pickup truck in open parking lots on weekends. Studies on the behavioral ecology of supermarkets and farmers’ markets shed light on their distinct social differences, the consumer response to each, and the values, both positive and negative, found in the shopping experiences at each. Cleanliness, friendliness, efficiency, price, sociability, and happiness resulting from the experience were among the topics surveyed. In almost every category, respondents placed the supermarket on the negative end of the spectrum, and the farmers’ market on the positive end. Face-to-face interactions with producers, whom customers consider trustworthy and who increase customers’ knowledge about the origins of the food they consume, are the preferred shopping experience (Gale 1997).

What has displaced the urban marketplace during the past century? What changes in modern societies have caused the gradual and sporadic reappearance of marketplaces in cities and towns? What is the role of architecture in reviving the contemporary urban market? Specifically, how do the evolving urban food initiatives in Central Texas determine the functions and relationships between a context of struggling communities and the modern urban marketplace? The published work about what constitutes the architecture of the market is surprisingly sparse. In fact, a collection of old postcards from David K. O’Neil’s private collection for the Projects for Public Spaces (PPS) effort was the only source that revealed the architectural beauty of markets in the United States. Unfortunately, most of the markets depicted have been demolished (O’Neil 2013).

Commercial Food Production and the Decline of the Traditional Marketplace

The decline and displacement of the marketplace in the United States is due in large part to the growth of commercial food production. The shift from local to global food distribution, which occurred with the rise of dependable highways and improved transportation systems after the Second World War, was noted by Monika Roth. The supply-demand chain became less dependent on local farming, and “big box” supermarket chains started utilizing central warehouses to distribute goods. Roth affirmed that small producers eventually “went out of business or turned to direct marketing” (Roth 1999).

High-demand, large-scale aggregation of products, as well as quality control protocols, were introduced with the advent of streamlined food production and distribution. The shopping habits of urban populations changed with the emergence of local supermarkets and grocery store chains. As cities and suburbs grew, consumer habits became more efficient and “pre-packaged.” According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), there currently are more than 8,100 farmers’ markets nationwide, an increase of almost 5,000 from the previous decade (Johnson, Aussenberg, and Cowan 2014).

Consumer Response to the Decline of the Traditional Marketplace

The increased interest in reviving the marketplace in recent years perhaps has been due to the public’s sense of social isolation and desire for more personal interactions (Roth 1999). The social dynamic of the grocery store or supermarket experience has given way to a desire for shopping as a “personal experience.” As Roth noted, consumers have “moved from a price/product orientation to a value/experience orientation,” and that farm direct marketers “have changed in response to changing consumer interests and lifestyle” (Roth 1999).

Consumers are not the only ones desiring this type of personal exchange. As Fred Gale reported, a survey of vendors at nine farmers’ markets in rural New York found that the primary reasons identified by vendors for selling in this venue related to social interactions. Gale, for example, quoted a farmer who said, “We enjoy visiting with customers and other vendors.” The social aspects of the venue were rated higher than “We want extra income,” or “Our other sources of revenue are limited.” It also is likely that many of the small, urban-fringe farms, that participate in direct selling are run by part-time farmers who depend primarily on off-farming income sources. For the operators of these farms, the motivation to farm is often non-economic (Gale 1997). In another study, conducted by James Kirwan, a respondent who was a producer from Wiltshire, U.K., stated that

I want to be dealing with people directly and to be producing the food that people want, rather than just producing some commodity that gets shipped off somewhere and processed. It’s making the farm more visible to the local population, bringing them back in touch with food production. (Kirwan 2006)

The traceability of food products, especially produce, also is becoming more important to consumers, who increasingly value products that are healthy and grown organically, with little to no pesticides. The perceived authenticity found in interacting directly with the producer has significant implications for the sudden popularity of the direct marketing of food products through farmers’ markets (Kirwan 2006).

THE ROLE OF THE MARKETPLACE IN CREATING A SENSE OF PLACE

Studies in urban design have highlighted that creating a sense of place is fundamental to the realization of the modern, public space (Salah Ouf 2001). The staff of Projects for Public Spaces, based in Austin, Texas, reflected on the growth of cities and noted that increased traffic and “greater road capacity are products of very deliberate choices to accommodate the private automobile,” and that city planners could instead “design our streets as comfortable and safe places for everyone” (PPS 2014).

In this manner, the marketplace helps public spaces thrive in cities and towns throughout the world. Designing the built environment around the market in a way that creates a sense of place is vital to the success of these public spaces (Watson 2009). In Melbourne, Australia, for example, City Council House 2 is a municipal office building, the staff of which seeks to increase the number and vitality of public interactions within the surrounding communities by being “connected to the surrounding neighborhood, fostering street life and creating a strong sense of place,” by using architectural design elements that result in “a comfortable place and an integral part of the community” (PPS 2014).

The market, in that sense, becomes both origin and destination, helping community residents recognize and value the public space as integral to their collective identity. The market is more than merely a location where one obtains food and other necessities, but also embodies the community’s unique sense of place. It becomes what Ray Oldenburg called a “third place” that forms the “core settings of informal public life” and is host to “the regular, voluntary, informal, and happily anticipated gatherings” of people “beyond the realms of home and work” (Oldenburg 1989).

THE ROLE OF DESIGN ASPECTS IN SUPERMARKETS AND FARMERS’ MARKETS

Consumers are provided bland, sterile, and anonymous shopping experiences at today’s supermarkets and large grocery stores, and the farmers’ market redefines this experience by leveraging interactions between the consumer, producer, and merchant that are inherently trustworthy and personal. Sommer et al. identified a self-serving culture as featuring “[t]he process of de-socialization ¾ that is, the elimination of opportunities for human interpersonal encounters in the marketplace is accelerating in retail settings in general, and in supermarkets in particular” (Sommer, Herrick, and Sommer 1981).

Sommer et al. explained the behavioral ecology of both supermarkets and farmers’ markets, of which architectural design is a part. Customers’ circulation through the store and exposure to products were the primary differences between the two. The supermarket design intentionally prioritizes traffic flow, thus eliminating spaces where shoppers could hold conversations. Similarly, store aisles are designed to maximize product display and shopper pass-through, and eliminate the possibility of easy communication between people on opposite sides. As Sommer et al. noted,

Shoppers at the farmers’ market, however, are free to talk across the low stands or boxes containing fresh produce. Physical objects at the farmers’ market serve more as bridges than barriers. Farmers’ market customers carry hand baskets and paper bags which don’t increase conversational distance or block interaction to the same degree as shopping carts. (Sommer, Herrick, and Sommer 1981)

An ease of communication and personal interactions in their shopping experiences are increasingly sought by customers. Farmers’ markets have become both a shopping destination and a preserver of such interactions. Opportunities to change the social habits of consumers, build on public spaces in urban communities, and provide a necessary and widely desired pleasant and humane experience for the buying of groceries, have resulted from this trend. As McGrath et al. explained:

Farmers’ markets belong to a class of marketplaces experienced by consumers in a very particular way. The structure of such markets unfolds along the dimension of a formal-informal dialectic, and the function along that of an economic-festive dialectic. (McGrath, Sherry, and Heisley 1993)

Such markets exhibit great semiotic intensity; that is, the tension of the marketplace structure and function is “palpable to participants and seems to energize them as well” (McGrath, Sherry, and Heisley 1993). Karen Franck, in her article “The City as a Dining Room,” gave profound insights on the importance of architecture in the revival of the marketplace. She noted that the city functions as “dining room, market, and farm,” and that Modernism’s “segmented and sterile” approach to dining and shopping should be replaced with “a correct mixing of land uses” that creates “places and ways for growing and selling local produce as well as for consuming it” (Franck 2005).

EXAMPLES OF A PERMANENT MARKET AND A FOOD HUB

Permanent Market: Pike Place, Seattle, Washington

One of the few successful examples of a permanent market in the United States today is Pike Place Market in Seattle, Washington. Factors such as strategic planning, an excellent site and location, an appropriately sized marketplace, and a diverse, culturally rich larger community helped it succeed after being renovated (Fig. 1). Factors that play a critical role in its ongoing success include the existence of the market as a well-known landmark before renovations, the gradual building up of vendors and tenants, and the shift toward social consumer habits at farmers’ markets in general. Operating since the early 1900s, Pike Place hosts ninety to one-hundred-twenty farmers and artisans in a central urban public market, while housing permanent restaurants and shops (including the original Starbucks coffee shop and Sur La Table kitchenware retailer), which collectively generate more than $100 million in annual sales. Approximately sixty percent of the ten million annual patrons are tourists including 900,000 from cruise ships (TXP 2013).

Organized as a redevelopment authority, Pike Place owns and manages fourteen buildings on nine acres, including three-hundred-fifty affordable apartments for the elderly, centers for children and the elderly, and a medical clinic. David O’Neil, an international market consultant and expert in the management and development of public markets, spoke of Pike Place’s relevance to the emergence of similar permanent markets across the United States, noting that “there’s been an enormous revival of interest in these markets,” and that these markets often begin in “some public open space but they can mature into covered market sheds” and other, more sophisticated and permanent physical structures (PPS 2014).

Food Hub: 21 Acres Center, Seattle, Washington

Operations on a larger scale than the marketplace are known as food hubs. The green-built 21 Acres Center for Local Food & Sustainable Living, just outside Seattle, Washington, is a comprehensive campus with a farm, school, food hub, commercial kitchen, and market. The site is the region’s first operating, community-oriented food hub, aggregating regionally produced food and delivering it across Seattle and Tacoma. It also helps local farms increase their profitability by providing a central point of purchase, thus reducing the logistics related to travel. The Puget Sound Food Network, which is associated with 21 Acres, supports increased production, distribution, and consumption of regionally produced foods (TXP 2013).

METHODOLOGY

In this section, case studies in the design and construction of two urban markets in Central Texas, one in the state capital of Austin (population 932,000), and the other about 100 miles to the northeast, in Bryan (population 76,000 and adjacent to College Station, population 106,000), are presented. Platforms for engaging university students in active and dynamic learning experiences in community development through project planning, budgeting, and scheduling, as well as facility design and construction, were offered by each project. The objective of this paper is not to compare the case studies, since one was designed and built, and the other was designed only. Instead, a contribution to architectural education through the power of design research, and an unconventional engagement with many entities outside academia in reviving the marketplace, are explored. Since post-occupancy evaluation was not possible, the author relied on the scholarly literature to measure design decisions and on experts to evaluate the proposals.

CASE STUDY ONE: AUSTIN PUBLIC MARKET (MASTER PLAN + DESIGN)

Recommendations for additional feasibility studies related to the creation of permanent food markets and food hubs, based on findings that highlighted the significant economic value of the food sector, were made in a recent report by the City of Austin on the economic impact of Austin’s food sector. The enhancement of Austin’s food sector and a projected increase in economic and social benefits to both visitors and residents were linked in the report (TXP 2013). Total sales activity in Austin MSA food-related sectors exceeded $10.6 billion in 2012, and provided about 100,000 jobs (TXP 2013). The study stated that the local marketplace is a valuable component in the revitalization of urban communities. Setting a precedent that is growing both in popularity and relevance, the farmers’ market (or direct marketing of food stuffs in general) can provide direct and tangible benefits socially, environmentally, and economically. These include retaining land for productive agricultural use, adding to the community’s economic diversity, providing meaningful employment, supporting local businesses, utilizing local resources, and adding to the tourism industry. According to Roth, farmers’ markets are “proven business incubators” that have “helped to revitalize urban centers and bring back a sense of community” (Roth 1999).

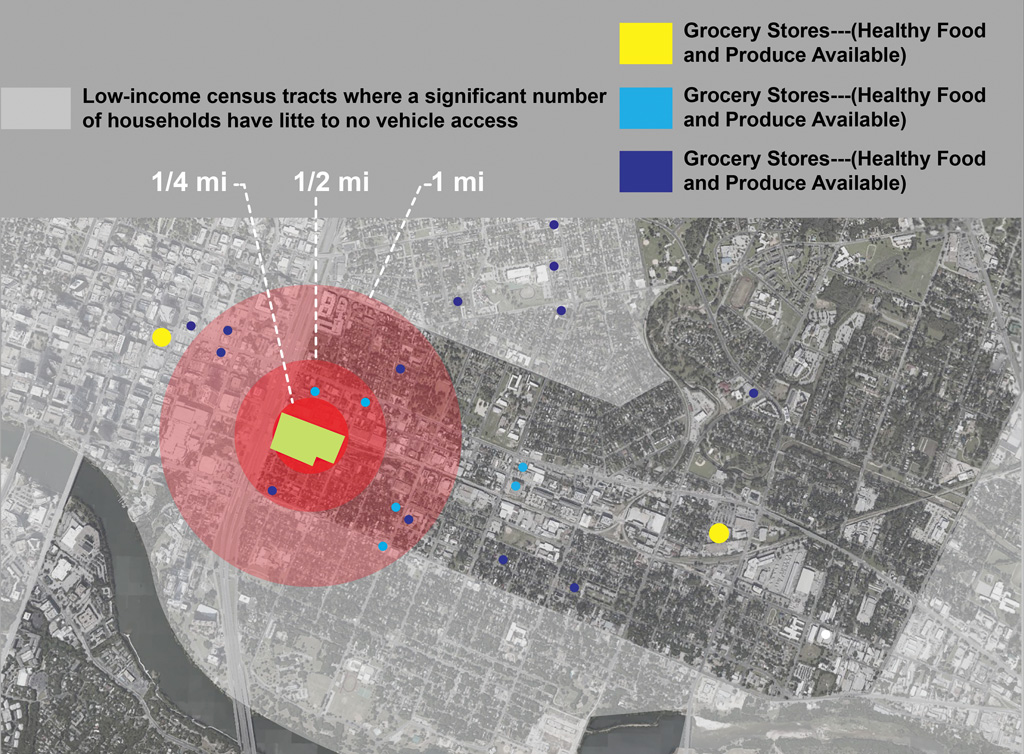

A design proposal for a major, permanent public market in Austin, which was initiated, researched, and designed by Zach Wise under the direction and mentorship of the author, was the first project. Establishing a sense of place within the East Austin community, reducing food deserts within the city, creating an attractive and vibrant public space, and building on Austin’s growing urban food and agriculture sector, were the project’s objectives. Through the design of buildings that supported a sense of place (in this case, in East Austin) the market could enhance the vitality of the community infrastructure and increase the connections among residents of the surrounding neighborhoods. Furthermore, through collaborative qualitative research conducted with respondents from the Sustainable Food Center (SFC) and the Projects for Public Spaces (PPS) in Austin, it became clear that the city was ready to take a leadership role in “food urbanism” and establish a permanent, public market similar to Seattle’s Pike Place Market. An area of approximately three and a half city blocks directly east of downtown Austin and Interstate 35, where access to healthy, fresh food is limited, was selected as the site (Fig. 2) .

Given that local markets are considered catalysts for urban vitality and economic growth, the proposal positioned the market as a place of commerce for local businesses, which could play a significant role in the area’s socio-economic revitalization. Successful markets in major cities generally are not broad, central markets, but rather are a network of strategically placed, small markets. Therefore, this project was intended to bring together the residents of a culturally isolated and diverse community. An understanding of urban regionalism and ecological design within the context of Austin gave insight into the potential role of an urban marketplace in creating social and economic vitality and cohesion in an otherwise divided community. The marketplace was envisioned as a social, public space with permanent and temporary market stalls to allow both ongoing and temporary market activities. Areas for community-supported agriculture and subsistence farming, as well as for educational programs, were preserved in the proposed site master plan. Providing these spaces, along with areas for small-scale agriculture and gardens, and variable, outdoor public spaces for both coordinated activities and leisure, was important (Figs. 4a, 4b).

Project Goals, Objectives, and Criteria

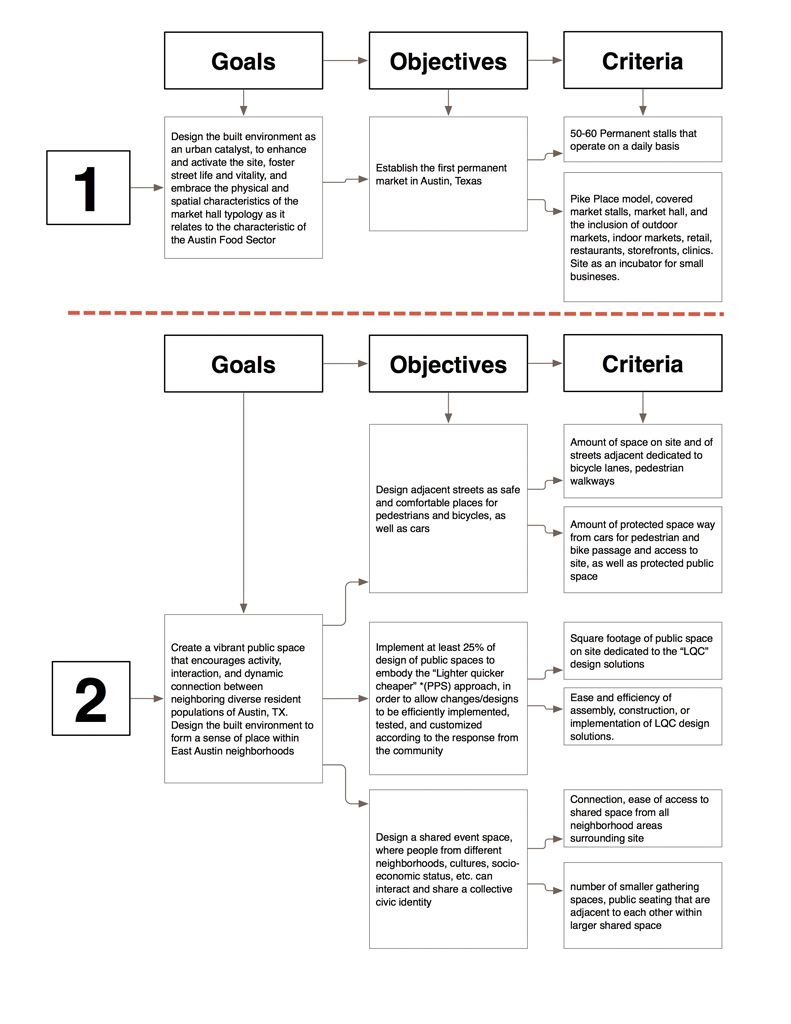

A review of the literature, as well as field studies and intensive engagement with the East Austin community and potential project stakeholders, resulted in the development of seven goals that formed the basis for master planning and site design. Strategic objectives that included measurable evaluative criteria were the basis for each goal (Figs. 4a, 4b). The seven goals were as follows:

- Design the new marketplace as an urban catalyst that would enhance activity at the site, foster street life, increase community vitality, and embrace the physical and spatial characteristics of the market hall as it relates to the Austin food sector.

- Create vibrant public spaces that encourage activities, social interactions, and dynamic connections between the diverse resident populations of East Austin. Create a sense of place within East Austin neighborhoods.

- Reduce the number of “food deserts” in East Austin and provide opportunities for easier access to healthy food in the surrounding communities.

- Facilitate the organization, development, cooperation, and implementation of the variety of urban food applied systems and research in cooperation with higher education institutions and research centers in Austin.

- Provide opportunities to celebrate and express cultural diversity, and cultivate community development, in these East Austin communities.

- Provide opportunities for community involvement and education in the areas of urban agriculture, nutrition, recycling and adaptive reuse, technology, and design for social impact.

- Create a practical and ecologically responsible facility within the master plan of the site.

Based on a site analysis and feedback from the community and industry experts, six strategies to achieve the desired goals were proposed (Fig. 5) . A permanent market, intended to be an urban catalyst, was designed for the north side of the site, and a food boulevard (where the original train tracks bifurcated the site) were added to connect the surrounding communities as a public space. A food hub, to be established at the southeast corner where a new train station is planned under the city master plan; an open space on both the north and west sides to celebrate diversity; and several Agri-Pods, the author’s unique solution to facilitate efficient urban agriculture and community gardens in Central Texas; and a recycling/composting facility to integrate natural systems, also were included.

These goals were addressed in the initial site master plan, which served as a foundation for discussion with community members and obtaining feedback from experts at the Austin Sustainable Food Center, Downtown Austin Alliance, and other organizations. Inputs from experts were addressed through several iterations until consensus was reached. Objectives and criteria were tied to the project goals in a diagrammatic matrix that was used in soliciting feedback, and that helped participants make design decisions.

Agri-Pods: A Unique Solution to Urban Agriculture

A raised-bed solution to small-scale agriculture was transformed into an architectural proposition. In contrast to big box grocery stores, the Austin Marketplace would consist of cast-in-place concrete boxes, ranging from 100 square feet to 300 square feet, called “Agri-Pods,” to be situated between linear, butterfly canopy roofs to harvest rainwater. The boxes had two parts: a rooftop agricultural bed and a vendor space below, connected with exterior stairs and a network of sky bridges. The Agri-Pods are the permanent individual vendor spaces and are linked for pedestrian access, while the adjoining timber butterfly pavilions serve as temporary stalls for suppliers, as well as an outdoor leisure area (Figs. 6, 7).

A passive cooling strategy is implemented through the walls of the Agri-Pods. The depth of the roof structure, along with multiple layers of soil and a drainage system, provide thick thermal insulation for the indoor area, as well as protection from direct sun exposure. The walls, designed in the “Trombe” system, allow warm air to pass through a wet pad, then drop and circulate within the space. This type of natural and passive cooling is common to many public markets (Fig. 8) .

CASE STUDY TWO: BRYAN URBAN FARMERS’ MARKET (DESIGN + BUILD)

The second case study was designed and built by an interdisciplinary group of university students majoring in either architecture or construction science as part of a university curriculum in design/build education. The process from design to realization spanned a full academic semester. Collaboration with city officials and professional engineers, preparation of construction documents, and securing the building permit were all performed by the students. The City of Bryan is located in the heart of the seven-county Brazos Valley. Its total area is approximately 44.5 square miles. Bryan was incorporated in 1871 as a small-town stop along the state’s expanding railway system (University of North Texas 2016). It quickly grew into a thriving, permanent center for agriculture, business, and trade, which helped set the city apart from similar train stops across the state.

The arts and culture that characterize Bryan are recognized nationally, especially since the town is adjacent to College Station, home to the world-class Texas A&M University. The distance between the nearest College Station city limits and downtown Bryan is about four miles. College Station, which grew up around Texas A&M and was not incorporated until 1938, does not have a central downtown area. In the 1970s and 1980s, shopping centers were built in other parts of Bryan-College Station, putting a strain on downtown Bryan that caused its steep decline. The downtown area, however, currently is experiencing a remarkable urban revitalization, with numerous activities to introduce people to the city’s culture and commerce (Burris 2009). As stated in a City of Bryan report, “In the late 1980s, a movement toward downtown revitalization began in Bryan, bringing businesses and interest back to the downtown area. Today, businesses are opening, expanding, and relocating in Downtown Bryan, breathing new life into the area” (City of Bryan 2016).

The deterioration of downtown areas is a problem in many American cities. A shift in traffic and shopping patterns, the development of new businesses and regional shopping centers elsewhere, vacant and dilapidated storefronts and homes, increased levels of crime, and a lack of funding for revitalization, all contributed to this decline. Today, many cities are investing in their downtowns in hopes of transforming them into thriving urban districts. The establishment of regular public events showcasing downtown merchants, music, and food is one popular strategy. Ongoing public events help drive positive awareness of a city’s downtown and make area residents aware of the many unique opportunities that exist there. Farmers’ markets and music festivals are examples of the kinds of activities that draw people to downtown. In addition, these events, as well as special tours, give residents an overview of the historic buildings and cultural landmarks that often are found in downtown areas and are important parts of a city’s unique heritage.

The farmers’ market currently held every Saturday in an open parking lot in downtown Bryan is not the city’s first. A recently published photograph revealed that there used to be a permanent, covered farmers’ market, apparently built in 1925, on the east side of the railroad tracks at the present-day intersection of William Joel Bryan Parkway and Tabor Road (Fullhart 2015). In the photo, several 1930s-era cars are parked around the market, and people are buying and selling goods throughout the entire area (Fig. 9) . In the background, several buildings that are still standing today are visible. According to historians, the market was closed in 1960, and the site was sold to a local businessman, who converted it into a parking lot (Costa 2015).

The current weekend market consists of approximately thirty-two vendors from the Brazos Valley Farmers’ Market Association, who use portable tables and tents that they install and uninstall each week. Acknowledging the logistical issues associated with temporary farmers’ markets, and redefining the role of architecture within a community, the Design + Build Interdisciplinary Studio in the Texas A&M University College of Architecture approached the city and the Farmers’ Market Association and offered to design and build a permanent farmers’ market structure as a service learning project for architecture students. As part of this effort to make a big impact through a small-scale intervention, as well as to demonstrate the power of design to enhance the community, the College of Architecture awarded a small grant and made available a fabrication facility. Meetings with city officials and members of the Farmers’ Market Association were conducted to better understand the association’s needs and the operation of the weekend market. Through a partnership between the City of Bryan, the Farmers’ Market Association, Texas A&M, and several local professional engineers, the project was launched in fall 2015.

Small-scale, pavilion-type markets are not only great incubators for the small businesses associated with them, but also provide projects of a manageable size and scope for semester-long design/build university curriculums. The success of the recent two markets designed and built by architecture students in Virginia and North Carolina as part of the new design/build education model offered in schools of architecture is a testament to the power of design in reviving the small-scale urban marketplace (Dvorak and Ali 2016). For example, gardens near a farmers’ market encourage the public to get hands-on instruction in gardening, while also providing healthy produce and a venue for positive social interactions. Many special events, such as the annual Blues Festival and Texas Reds Festival, and monthly First Fridays, are held in downtown Bryan throughout the year. Since the farmers’ market site is near downtown, spaces suitable for activities associated with these specific events were designed and placed within the project site.

Project Goals, Objectives, and Criteria

The designated site near downtown Bryan is approximately two acres. The east boundary is public parking for St. Joseph Catholic Church. There are two historic structures on the site: a residential house dating to 1871 and a carriage house dating to 1880. The remainder of the site is undeveloped, with a few trees. All of the surrounding properties on the block are publicly used. Since the site was designated for public use by the city and the gifting foundation, a master plan for the entire two acres was necessary (Fig. 10) . The following five objectives were identified through meetings with city officials, community residents, and representatives of the funding entity:

- Propose a program to reclaim the site and enhance it economically, socially, and ecologically.

- Provide connectivity to surrounding properties, such as St. Joseph Catholic Church.

- Provide greater context between the site and the community.

- Provide new features and characteristics in re-imagining the identity of the site.

- Provide spatial quality for the program’s proposed activities.

Along the site’s south boundary, a long, permanent farmers’ market designed as a modular pavilion unit, named The Tree, was proposed. The Tree unit acts as an autonomous shading structure, with a multilayered roof stemming from a cluster of columns. The proposed series of identical sections, placed side by side, creates a row of farmers’ market stalls. Each section, or “tree,” provides approximately 100 square feet of shaded area (8 x 12 feet of vendor space) supported by a cluster of four 6 x 6 inch timber posts. Traditional Japanese architecture inspired the market structure: repetition is the logic of the roofing system, and the design serves both structural and architectural needs.

The outdoor market structure was designed and built by university students majoring in architecture and in construction science. The effort was part of Real Projects, a community outreach initiative that engages college students from multiple disciplines in projects benefiting communities in the Brazos Valley (Fig. 11). The planning, design, pre-construction, and construction of the Bryan Farmers’ Urban Market were carried out by these students. The interdisciplinary studio worked collaboratively during the entire design and build process. The studio was divided into three teams, each assigned to produce specific documents required for obtaining the building permit and building the pavilion.

The power of architectural design and the efforts of the students participating in service learning were leveraged through the project to make a direct, positive impact in the Brazos Valley. A space and shelter where local farmers could sell produce, and where residents could have an outdoor “living room,” was provided by the permanent market. The pavilion is used for musical performances and classes on farming and nutrition. The permanent pavilion, designed to be both beautiful and functional, encourages residents to develop a greater appreciation for architecture, and a greater practical understanding of the importance of a healthy lifestyle. The engagement between a top-tier research university, local residents, professional consultants, and city officials was a successful example of designing for social impacts that improve the quality of life for both project participants and end users.

ARCHITECTURAL EDUCATION FOR POSITIVE SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS

At a time when the cultural differences and diversity that could enrich a city’s social fabric are under threat due to political agendas, the marketplace appears to be a possible missing link for healing divisions and restoring trust by offering a unique opportunity for people of all ages, and from all cultures, social classes, and walks of life, to interact and build mutual respect. The biological necessity for food is not separate from the social need of humans to interact, which makes the market an excellent facilitator of interaction between those who otherwise might not ever come into contact with each other. People whose lives are seemingly disparate in every way would benefit from the chance encounters and interactions that inevitably occur at such a place.

In both cases presented in this study, enhancing the development of urban communities through engagement between university students participating in real-world architectural education and residents of the university’s adjacent communities was the overarching goal. Because the marketplace was positioned to become a venue where diversity within the community would be celebrated, conducting all aspects of planning, design, and construction using comprehensive community input and participation was critically important. Community involvement at every step of the process, and empowering citizens to advocate for themselves, are encouraged by this participatory strategy. Texans in East Austin and Brazos County could benefit profoundly from this approach. The involvement of residents in the surrounding communities in jointly providing input on their specific needs for a public space, and the subsequent organized community response, ultimately resulting in the creation of a shared public space, also could be a development tool for uniting a divided community.

Unexpected solutions to complex problems are offered by architecture in the facilitation of unconventional social engagement. Whether in a major city such as Austin, or a smaller town such as Bryan, the architecture of the marketplace encourages and cultivates inherent social dynamics, provides the opportunity for cultural expression, and promotes community cohesion and economic development. Ecological design in the practice of adaptive reuse, construction processes, and the harvesting of materials, is informed in the marketplace by local agriculture, farming, and artisanship. A market could be a module, an urban catalyst for growing a network of community markets within the urban fringes of a city or town. As demonstrated in these case studies, architecture has the power to offer synthetic solutions to highly complex problems, and all of these solutions begin with the education of the architect.

Brown, Allison. “Farmers’ market research 1940–2000: An Inventory and Review.” American Journal of Alternative Agriculture 17, no. 4 (2002): 167-76. doi: 10.1079/AJAA200218.

Burris, Charlie. “The Revitalization of Downtown: The Birth and Rebirth of Bryan, Texas.” Archivoltum (March 2009).

City of Bryan. “Downtown Bryan History.” Brazos County History: Rich Past-Bright Future, 2016.

Costa, Chris. “Downtown Bryan to Become Permanent Home to Brazos Valley Farmer’s Market.” KAGS (2015).

Dvorak, Bruce D. and Ahmed K. Ali. “Urban Agriculture Case Studies in Central Texas: From the Ground to the Rooftop.” In Urban Agriculture. Edited by Mohamed Samer, chapter 2, 3-20. InTech, 2016.

Franck, Karen A. “The City as Dining Room, Market and Farm.” Architectural Design 75, no. 3 (2005): 5-10. doi: 10.1002/ad.70.

Fullhart, Steve. “Back to the Future: Farmer’s Market Moving into Downtown Bryan Area.” KBTX, 2015.

Gale, Fred. “Direct Farm Marketing as a Rural Development Tool.” Rural Development Perspectives 12 (1997): 19-25.

Johnson, Renée, Randy A. Aussenberg, and Tadlock Cowan. “The Role of Local Food Systems in U.S. Farm Policy.” Congressional Research Service, 2014.

Kirwan, James. “The Interpersonal World of Direct Marketing: Examining Conventions of Quality at UK Farmers’ Markets.” Journal of Rural Studies 22, no.3 (2006): 301-12.

McGrath, Mary Ann, John F. Sherry, and Deborah D. Heisley. 1993. “An Ethnographic Study of an Urban Periodic Marketplace: Lessons from the Midville Farmers’ Market.” Journal of Retailing 69, no. 3 (1993): 280-319.

O’Neil, David K. “The 10 Greatest US Public Markets that Met the Wrecking Ball.” Project for Public Spaces, 2013.

Oldenburg, Ray. The Great Good Place: Cafés, Coffee Shops, Community Centers, Beauty Parlors, General Stores, Bars, Hangouts, and How They Get You through the Day. 1st ed. New York: Paragon House, 1989.

Project for Public Spaces. “Ten Strategies for Transforming Cities and Public Spaces through Place-Making.” PPS, 2014.

Roth, Monika. “Overview of Farm Direct Marketing Industry Trends.” Agricultural Outlook Forum, 1999.

Salah Ouf, Ahmed M. “Authenticity and the Sense of Place in Urban Design.” Journal of Urban Design 6, no. 1 (2001): 73-86. doi: 10.1080/13574800120032914.

Sommer, Robert, John Herrick, and Ted R. Sommer. “The Behavioral Ecology of Supermarkets and Farmers’ Markets.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 1, no. 1 (1981): 13-19.

Watson, Sophie. 2009. “The Magic of the Marketplace: Sociality in a Neglected Public Space.” Urban Studies 46, no. 8 (2009):1577-91. doi: 10.1177/0042098009105506.

The author would like to thank the College of Architecture at Texas A&M University for funding this research initiative. Special thanks also go to the Center for Housing and Urban Development; Professor Bruce Dvorak, Dr. Ben Bigelow, Dr. Shannon Van Zandt, and Professor Michael O’Brien; Mr. Karl Hoppess with the Coulter & Lilly Rush Hoppess Foundation; Mrs. Leslie Guindi and Mr. Joey Dunn with the City of Bryan; Thomas Gessner and Niko Gomes with Gessner Engineering; Matt Macioge, farmers’ market manager with the Austin Sustainable Food Center; members of the Brazos Valley Farmers’ Market Association; graduate students Zach Wise, Kendall Raabe, Tiantian Lyu, and Jingwen Lu; and finally, the undergraduate students in environmental design and construction science in the spring 2016 ARCH 406 Interdisciplinary Studio class.

Figure 1: Photo by the Author.

Figures 2 and 3: Image by Zach Wise.

Figure 4a, 4b and 5: Figure by the Author.

Figures 6, 7 and 8: Image by Zach Wise.

Figure 9: Photo courtesy of the Downtown Bryan Association.

Figure 10: Figure by Jingwen Lu.

Figure 11: Photos by the Author.

Ahmed K. Ali, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of architecture at Texas A&M University. He has taught and practiced architecture in the United States, Italy, Turkey, and Egypt since 1998. Ahmed’s research and scholarship focus on the architecture of waste and the constructive technique in the materials and methods of conventional practice. His work explores the relationship between structure, construction, and tectonics. E-mail: ahali@tamu.edu