Professor in Residence, Department of Architecture, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

Miravalle is a relatively new neighborhood in Iztapalapa borough, by the eastern edge of Mexico City. It has been identified as a highly-marginalized area, as its 11,000 residents have poor access to public infrastructure, high rates of violence, and socio-economic discrimination is something most experience. Nonetheless, the community has worked together with the aim of improving the conditions and quality of life in a small but outstanding way. As a group of architects, we are working with them to transform the main park of the area and neighboring communities into a walkable and safe recreational area. The prerequisite for city life is a walkable urban environment. If a safe line crossing the park could help diminish the insecurity and strengthen the connections between people and space within the neighborhoods, then architectural interventions as a stead for social development are guaranteed.

Walkable urban environments are a prerequisite for civic life. Spatial qualities of the in-between mediate relationships that occur within and around buildings, neighborhoods, streets, and people. Stressing this point further, we believe that collaboration may be the sincerest way to highlight the importance of life activity that happens between these spaces, and how, as designers, partnering with local residents might meaningfully help explore ways in which we may further transform spaces to promote positive interactions within them. If a safe line that crosses a park can help diminish the insecurity and strengthen the connections between people and space, then architectural interventions as a stead for social development are warranted, at least on real scale.

A MARGINALIZED MARGIN OF THE CITY

When we visited Parque Corrales for the first time, Jorge, our community liaison opened up to us about Miravalle. The middle-aged teacher in the Marist Middle School, long-haired and thin, told us that after living there for twelve years, he felt “a sense of identification amidst the community because we all suffer from the same problems: gang fights, drug traffic and consumption, or water shortage. We only get water once a week, for two hours! We all live this, and that makes us understand one another and feel for the troubles we all collectively experience.” César, a young resident, expressed similar sentiments, “here the youth doesn’t have the education for talking and engaging in dialogue; they were taught that fighting is how one settles differences.”

Today, Mexico still remains one of the most violent places in the world. These disruptions affect millions like Jorge, largely the consequence of violent, drug-related crimes made worse by rampart government negligence. In some parts of the Mexican republic—Estado de México, Guerrero, Michoacán, and Sinaloa—the mortality rate is higher than in war zones. 1 Too often our only contact with violence comes through statistical figures we read on a page, but in places like Miravalle violence is manifest in other and much more painful dimensions affecting friends, neighbors, and loved ones.

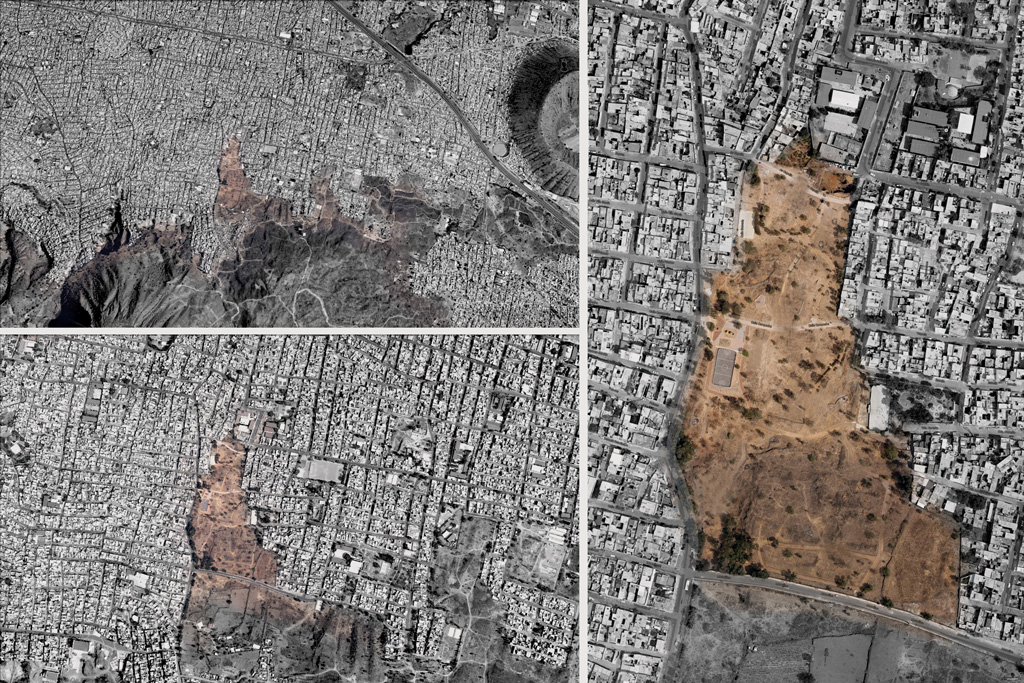

Miravalle is a relatively new neighborhood in Iztapalapa borough, on the furthest eastern edge of Mexico City (Fig. 2) . Rogelio Estrada, a member of the resident-led Asamblea Communitaria de Miravalle, spoke to us about the challenges facing Miravalle: "... first of all, this is a community with many needs. INEGI and official studies classify it as a highly-marginalized area.” 2 Residents here have poor access to public infrastructure and regularly experience socio-economic discrimination especially when, for example, many have menial day jobs in the capital where they are often treated like second-class citizens. Miravalle has around 11,000 inhabitants, most of them between twelve and twenty-five years old. 3 Less than 3 % of the population has attended high school or even received a middle school diploma. 4 Even if the will and social opportunity for the youth to attend school existed, educational facilities cannot meet the existing demand as they are often in run-down conditions. This educational deficiency is manifested in the community’s low income levels and high rates of violence. As Oscar Pérez, a manager at the local plastic thermo fusion workshop and member of the Asamblea, tells us, “adults feel a nuisance when they see so many youngsters in the streets with no work, no education, no prospects.” 5

Miravalle, like most other informal settlements in Mexico, is the result of complex social and historical processes. These can be briefly summarized as the rural exodus to urban centers by workers and their families who can only afford to settle in the cheap, underdeveloped urban fringes, places where municipal control or assistance pertaining to development are almost non-existent, and access to urban resources is severely limited. 6 Within a short period of time, these settlements have grown rapidly while lacking proper planning or access to urban services and infrastructure. Informal urban development without basic services may lead to identity problems and fraught social cohesion among inhabitants.

The Asamblea Comunitaria de Miravalle is a response to such aforementioned conditions, a community-based grassroots organization created in 2007 with the aim of improving the conditions of their neighborhood and optimizing resources into building spaces for the community and its development. Through the Asamblea, Miravalle’s residents have sought to create a resilient society, pave roads, install drainage systems, build small playgrounds, a recycling center, a cooperative communal dining room and an open dome theater - overcoming the marginal conditions and lack of resources they face day to day. They have collaborated with other architects or institutions, like the National University of Mexico (UNAM), whose expertise in social work recently helped transform a derelict lot into a vibrant urban center with an arts and crafts workshop named Calmecac. 7 This is a place where the at-risk youth can work and learn, or play "frontenis" instead of loitering around Miravalle potentially becoming exposed to gangs and violence. Working in cooperation with several architects and the local government, the community has successfully transformed some under-utilized spaces to a set of humbly build shared spaces with the goal of fostering a sense of community (Fig. 3).

With the invitation to participate in the 2016 Venice Architectural Biennial, Reporting from the Front, the project “Walk the Line” was conceived –apropos of the theme-– as an architectural intervention that could aid and ail a specific community. The effort was a collaboration among Tatiana Bilbao Estudio, and Alejandro Hernández. In one of the first discussions concerning the proposal, Alejandro Aravena (curator of the 2016 Biennale) commented that the funds provided for the Biennale were enough to build two units of social housing in Mexico. Rozana added that she was already involved with the Miravalle community, and we immediately decided to take on the challenge of helping transform the neighborhood. We wanted to initiate an immediate and lasting positive change on a place in need of a small-scale restructuring gesture. With the task before us, we established a joint-fundraising effort to match the amount of the Venice Biennale grant.

All of the aforementioned firms see the architect’s role as improving people’s quality of life through spatial means. We favored a simple intervention but one whose social implications would initiate a broad, positive and lasting social transformation. It wasn’t until our first visit to Miravalle, first interviews and field work, that we settled on Parque Corrales as the site where we could have the maximum possible impact.

Situated at the limit, the threshold between the neighborhoods of Miravalle and San Miguel Teotongo, an empty lot had become an impromptu park somehow overlooked and forgotten by the relentless pace of the explosive informal urban sprawl. As a neglected natural reserve and a potential link between four surrounding neighborhoods the site presented a real opportunity to work toward residents’ and the assembly’s vision of forging a true sense of community. Although it was a strategic piece of land with tremendous potential, Parque Corrales had the reputation as a hotbed of muggings and violence throughout the largest part of the last decade. Residents had not yet figured out how to transform such a valuable piece of land into a community recreational space, despite other successes in renovating other neighborhood spaces.

Due to the potential danger in crossing the park, many residents chose to spend more time and money circumventing the park to get to and from homes, schools, and businesses. Some people like young middle school teenagers, while crossing it to get to school or walking back home had little choice but to risk a possible mugging or exposure to potential sexual harassment. Cristina, one of the middle-schoolers we interviewed, told us how she had already been mugged four times. When asked why she continued to cross the park after such experiences, she explained that she preferred the potential risk over the forty added minutes to her commute that circumnavigating the park entailed. We were shocked to realize how such a state of permanent insecurity had become normalized, how experiencing danger, violence, and insecurity had become a part of that community’s identity.

The topography of the park grounds had been eroded by natural elements; in addition, the pedestrian paths in the park were lined with heaps of trash.

The budget for the lamp posts and site reconstruction was roughly the same as for the sixty-meter path installation built for the Venice Biennale. The idea behind building an illuminated path at Miravalle was to partner with an at-risk, marginalized community already thinking about its social needs and working towards solving its problems. To achieve such goals, partnering with other institutions became a key part of the project.

A proposal for a site transformation cannot merely be an isolated gesture, however well-intentioned or poetic. It is not enough. We sought to determine a plan of action to build relationships among people, the spaces they occupy and the objects they interact with. The inaugural intervention consisted in a line of actions that aimed to reinforce relations between people and raise awareness of the space they inhabit and how they inhabit it, instead of underlining the antagonisms of their own community reflected in the park.

The first stage of our intervention involved illuminating a 360 meter path through the entire length of the park. The idea behind the light path that could act as a bridge — not only interconnecting the surrounding areas, but also interlacing its people — was to be a line of recognition, a lit trail, a dialogue, a conversation and a catalyst of safety. Because design by itself cannot fix social ails, we made sure to enrich the process by working alongside the community with the hopes of building a real connection among the park borders, its different neighborhoods and the inhabitants of the greater region of Iztapalapa. By creating a safe way to cross and inhabit the void while working with the community, we could leverage the power of design to enact a positive and transformative chain reaction in the spatial use of that particular area. More specifically, working with a self-managed community became a key feature of the project, since we did not want to appear as outside actors that produced an external project; hence, it was our thinking that, by working alongside the Asamblea Comunitaria, we could together conceive a comprehensive and coherent action manifested into a particular space.

We are aware that lighting fixtures alone cannot eradicate the insecurity of an area, but by providing a well paved and illuminated path, we hoped it would help create a more welcoming environment which would .increase transit and maybe, in the the long haul, transform the derelict lot into a park buzzing with activity. Meanwhile, we hoped it would also demarcate a space of reinsured interaction, a “place of encounter” — as Henri Lefebvre would call it — where other public activities can take place. A transformation of such nature can only occur through an active social practice of space. To pursue such change into space we ought to construct the medium for positive interactions to unravel, while cancelling negative ones.

An urban transformation towards a safe area is simultaneously the cause and result of more people circulating around public spaces. Walkable places must, by definition, have a reasonably cohesive social structure that provide safety, a sense of community and a healthy public life. The profession at large and our studio have learned from the mistakes and broken promises of the placelessness of the International Style Modernism. For such complex problems architecture cannot be the only solution, but in working together we can spark social changes through thoughtful, precise and punctual spatial interventions.

The collaboration with other architects and the local community highlighted the importance of the activity that happens between buildings and neighborhoods, the in-between, and how such partnerships might meaningfully explore the ways in which we may contribute further. The prerequisite for a civic life is a walkable urban environment. If a safe line crossing the park could help diminish the insecurity and strengthen the connections between people and space, then architectural interventions as a stead for social development are warranted.

OUTLINE ON THE GROUND

On March 7th, early in the morning, around ten architects from the participating studios set about a quest on the eastern border of the city (Miravalle), carrying three hundred meters of cable, one hundred light bulbs, and string. There we met up with photographer Onnis Luque, his team, and Jorge, who welcomed us in the Marist school (Fig. 4). The facility is a prototypical Mexican school with a large patio, the kind of schools built across the Mexican republic after architect Juan O'Gorman published his design for a modern school in 1930 - a clean, bare space, adequately lit, where Jorge kept the building tools: hammers, chalk, and sticks. 8

By the time we made it to the park, several community members were awaiting our arrival, eager to help. Together, we marked the line from one end of the park to another, with sticks and strings. We traced with chalk along the space, sprinkling the fluorescent white powder generously, following the original plan, nervous, unsure, but ultimately exuberant about the unseen, built, unearthed path which lays ahead.

Before noon we all paused to take a break until the sun, perched high in the sky, came down and the stilling, dry afternoon heat dissipated. We walked around looking for somewhere to eat something. During this time, the park’s potential and its urgent issues became manifest to us not just as anecdotes but as lived experiences by community members. As we sat under the dome, we could admire the recent project done by the Assembly in conjunction with the National University and enjoy .the simple pleasures that an evening of leisure in the Miravalle’s hillsides could provide.

We drank soda under a drooping tree beside the main road, next to the Calmecac, another community project by the Asamblea consisting in a community center and workshops for young kids, a frontenis court, and a basketball court.

Before dusk, our friend Rafael drove up the mountain with a gasoline-powered generator that we could connect to, in order to illuminate the path. At the same time, some of us were already placing the cable along the path we had previously marked, keeping it elevated with the help of the community passersby and residents willing to lend a hand.

After several unsuccessful attempts to provide the sufficient amount of power to light up all the circuit, success! We maintained the path lit for several minutes. We imagined how an illuminated line could render—even if only a small percentage—the path visible, and make a territory walkable. Suddenly, the light worked as some sort of telescope, or line retracing not just the site’s cartographic projections, but the neighborhood’s geography. The territory was rendered legible and could be understood immediately, helping to reinforce a sense of safety along the line. (Fig. 5)

Little did we know, darkness was an ally of people with more nefarious ideas, rendering them invisible. After a quarter of an hour gasoline battery ran out, as did Rafael’s car battery. During the following minutes, we folded the cable, removing the bulbs from their sockets. In the blink of an eye, just when darkness had swept in, blanketing our surroundings anew, we discovered that two light bulbs had already been stolen.

Had some residents been resentful of a group of foreign professionals? Perhaps. Were a couple of light bulbs an opportunity to score some quick cash? Most likely. Despite that, we not only felt, but could appreciate from our experience that afternoon, that the majority of people were happy during the symbolic event, and that alone was enough of a reason to carry on with the construction plans. It was a good sign, as well as an enriching exercise for us, and a feasible imaginative act for them, to continue working there.

This event was a statement and an experiment to see how the line could bring transformation in the blink of an eye. A few weeks later, the formal construction of the line began, replacing illogical semi-destroyed paths and formalizing the desired lines traced by residents’ activities into permanent paths.

THE VENICE BIENNIAL

It was not until the early days of May 2016 that construction began on site, coincidently during the same days that we were assembling the installation for the Venice Biennale Reporting from the Front. It was a beautifully intricate process: just as the Biennale visitors were watching a short video of the beginning of construction in Miravalle, the park transformation itself was taking place.

The installation for the Biennale consisted of a symbolic representation of the work that was taking place in the eastern edge of Mexico City. A thirty meter long line of light traced a path in the middle of the Artiglierie, connecting with the Central Pavilion of the Arsenale. (The Artiglierie is one of the many buildings comprising the large historic complex of the Arsenale, the old shipyard of Venice, where part of the Venice Biennale takes place – Ed.). The visual backdrop of the line was a projection wall, screening the worksite in Miravalle and connecting the light path with the real one across the sea. We wanted to stress the idea that “reporting from the front” was sharing our process almost in real time, hands on labor, transporting the visitor’s imagination to the actual construction site, including the spectator into the story. (Figs. 7 and Fig. 8.)

SUNDAY MORNING

It was almost a usual Sunday in Miravalle: the Tianguis, 9 religious confirmations, parties in the corners or sidewalks, roasted chicken and soccer matches in the small courts around the borough. But that morning of the 26th of July, we met at 8:00am with mothers and fathers that were summoned for their monthly community labor activity. This activity had in Miravalle a key part of its resident-led transformation.

The site had already been under construction for a few weeks. It was a slow process, but the once broken paths and unwalkable steep rocky roads had finally become smooth and uniform.

The families were ready for a robust working day. They came ready with picks, shovels, buckets, brooms, wheelbarrows, and grandmothers, brothers, children, uncles: all gathered in alliance for collaborative teamwork. They helped us unload the gravel out from the truck and lay it over the bare earth path that should become the Line. The families’ gathering was so enthusiastic that even the young kids wanted to chip in, moving gravel and sprinkling chalk.

A COMMUNITY INPUT

Co-working with the community was both the means and the end of the project. The Asamblea Comunitaria has been devoted to working restlessly with the Miravalle community for the better part of the past decade. As Rogelio Estrada, one of its members said, “I perceive a strength in my community: its will to change and not stay quiet sitting back and expecting others to speak for them. We all have an urge to speak out! We want to propose, to change, to go forward. This was the key reason which led to the assembly’s creation.”

The first time we visited the area, we asked the kids in the José de Tapia Bujalance school what they imagined or wanted the park to become. Light, hygiene, safety, surveillance, play spaces. These buzzwords kept popping up in all responses (Fig. 9). The first step to outlining the project guidelines and define our strategic approach was defining users’ needs, particularly those who would benefit most from the creation of the park, such as kids.

Working together, we could clearly communicate and understand residents’ problems, enabling us to channel our ideas and work into a simple and feasible architectural gesture. We believe that – without being ambiguous or esoteric - it should always be this way; after all, architecture is the spatial result of a service to the community. Jorge, as a community leader, kept telling us about how important it is that the community reflects on its own issues: “It’s not our task to tell them the solution. We need to search for answers together, it is a slow journey but we think that it is the most steadfast route to progress.”

There is no doubt that Miravalle is a self-managing community. It is an example of how collaborative efforts can render a community, especially the informal ones (which today represent the majority of the world’s built environment), more resilient, thus reinforcing social integration. In this case, the change was provided through the construction of cultural spaces within the neighborhood (for example: art education spaces for kids and youngsters, small scale cultural and ecological programs, etc.). Perhaps architecture can only contribute as a kind of “detonator” (a catalyst), for participation and involvement, staging a socio-spatial transformation, but it is an important role nonetheless.

AN UNPROMISING PANORAMA?

Light has a strong cultural meaning. It has enabled human activity to take place regardless of external conditions, revolutionizing fields such as medicine, entertainment, culture, communication, public life in cities, etc. Its role as an extension of time and space is of utmost importance. If announcing is like performing and light is activating, then collaborating is building. For this reason, the essay explores the collective effort that can reposition architecture as a social discipline, intimately related to and deeply invested in the transformation processes of its context.

Despite the sum of partners that we managed to add-up into the process, 10 such as The Rolex Foundation’s grant contribution and the aid of the company cm2, who worked so hard to manage the construction site pro bono, what at first glance seemed like a simple construction project transformed itself into a lethargic process, due to the scarce available resources that we were able to secure. An inaugural and noble intention turned out to be a portrait depicting a widespread national reality, underlining how projects full of promise and energy suddenly and unexpectedly become paralyzed. The financial viability of the project is currently in limbo, halting the next construction stage due to the lack funds.

As small or seemingly insignificant this project appears to be, it means a great deal for the people in Miravalle. For those of us who worked there, the project has been the opportunity to introspectively examine the potential impact architecture can have within anthropological, social and spatial limits. Nonetheless, it also underlines how simple projects as this are also extremely difficult, as they affirm how society collectively prioritizes self-preservation over the collective wellness. Projects like the Park in Miravalle, whose process could be applied also elsewhere to integrate informal settlements, have zero monetary utility and it is therefore difficult to devote them time or to secure the necessary resources when individuals are unwilling to experiment.

At the same time, this process demonstrates that, to a large extent, the project of building a Miravalle community has already been accomplished by community leaders and residents working in conjunction. The park and the light path serve as symbolic indicators of the community’s progress. Alas, these cannot by themselves create a community where one did not exist. Such built forms serve to strengthen relationships. Thus, while the life of the community depends on a network much larger and more complex than any park, the renewal of social bonds is why projects like these are so relevant, because a community must be constantly re-forged and made anew every day, or these social bonds will fall into disrepair and the built environment will soon follow suit. Maintaining the process alive is what the built environment, as a host for public interactions, can contribute to the overall dialogue of community and place-building.

We are eager to continue with the second phase of the construction work and truly say that it is possible to “walk the line” across the park, but we are also conscious that there is a much longer path to walk in terms of collaboration between architects and communities after this project.

We are still making an effort to raise the necessary funds to complete the project, which grew in scope from a simple lighting path to a comprehensive park masterplanning effort throughout our involvement. We wanted to negotiate with the community a long-lasting, well illuminated and lively park, rather than just installing a few lighting fixtures.

The promise of the evening of March 7th still shines brightly in our memories as a glimmer of what may be, when for a few glorious minutes as the sun set over the western edge of the Sierra Madre Sur, the path forward was illuminated for all to see.

Views of the path illumination on March 7th, Parque Corrales. Photo by Onnis Luque. See full video at https://vimeo.com/179496861.

According to the National System of Public Security (Sistema Nacional de Seguridad Pública [SNSP]), the mortality rates in 2016 broke records, with 6,576 homicide cases nationally due to violence, only between January to April. That means 56 victims a day. Within this time frame, 728 homicides happened in Estado de México, 692 in Guerrero, 371 in Michoacán, and 330 in Sinaloa.

National Institute of Statistics and Geography (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Geografía - INEGI).<

According to the INEGI, 60 % of the population, that being around 6,000 young people.

In addition to what statistics reveal, Oscar Pérez said “schools may be even two hours away from the kids’ homes, and doing this journey twice a day wears them out, and that is one of the reasons why they drop out of school.” César said “the majority only reach middle education, to say the most. Nowadays, some venture to start high school, but most of them only study through middle school. Their parents tell them how studying doesn’t take them to earn money, stressing how important it is for them to start working as soon as possible.”

The thermo fusion workshop consists of a place where the youngsters can work recycling plastic residues from the neighborhood and turning it into chairs, vases, artworks. When selling the pieces, the money the earn can partly become part of a fund for further projects of the Asamblea Comunitaria.

“Everyone located where they could. This land was commonly owned, but, when it started to be sold, people started to build their houses with cardboard; cardboard actually became a symbol of Miravalle. Little by little, with the help of local government programs, they built their homes with concrete blocks and other (more resistant) materials. This is one of the characteristic things in this place, people would invest their scarce money in construction or construction materials. Then they build a floor or two more than what they need, so they can rent a room to someone else and obtain some extra income.” (Jorge Carvajal, member of the Asamblea Comunitaria de Miravalle.)

This was possible after the funding the Asamblea received from the Urban Age Price, Deutsche Bank, in 2010. As well as an urban agriculture center, they recently started building in San Miguel Teotongo (neighboring Miravalle), with the aim to educate the younger generations about water harvesting, urban agriculture, and recycling, and, eventually, to supply food produce to the community dining room in Miravalle, where cheap and organic food can be provided to the inhabitants.

From the 1930s and following years, the Mexican architect Juan O’Gorman came up with a plan with the aim of building all the schools the city needed with the same budget that had been used in the past 10 years for building only one. Within that period, he developed a strategy for erecting low-cost modern modular schools, defining a radical functionalist Mexican style that would further be replicated across the country.

Informal market set on the street.

cm2, a construction contractor and development company, joined our effort as developers and builders. The Rolex Foundation funded part of the process, Flos provided us with lamps, Carlos Hano and Kova Innovaciones with lighting design, Cementos Fortaleza donated cement. Elementia, Eternit, Allura, CEMPanel, Wavin, and Amanco became sponsors or donated material.

Project: Tatiana Bilbao Estudio, Dellekamp Arquitectos, Alejandro Hernández, Rozana Montiel Estudio de Arquitectura.

Design team: Gabriela Álvarez, Nuria Benítez, Hortense Blanchard, Alba Cortés, Silvia Mejía, Valentina Sánchez, Antoine Vaxelaire, Geoffroy Arnux

Construction and development: cm2

Lighting design: Carlos Hano, Adrián Kohlmann Nava

Photography and video: Onnis Luque

Photo assistant: Daniel Maldonado

Photo editor: Xico Santana

Special thanks to: Asamblea Comunitaria de Miravalle, Laura Alonso, Rafael Álvarez, Steven Beltrán, Anna Der, Abraham Fonseca, Daniel Jaramillo, María Cristina Sánchez, Mario Pérez, Daniel Rivera, Soledad Rodríguez, Rodrigo Yáñez

With the support of:

Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, Agencia Mexicana de Cooperación Internacional para el Desarrollo (AMEXCID), cm2,The Rolex Institute, Flos, Elementia, Cementos Fortaleza, Eternit, Allura, Duralit, Plycen, Mexichem, Kova Innovación

Tatiana Bilbao graduated in architecture and urbanism at the Universidad Iberoamericana in 1996 and has been Advisor for Urban Projects at the Urban Housing and Development Department of Mexico City in 1998-99.

In 2004 she founded Tatiana Bilbao Estudio with projects in China, Europe and Mexico. She received numerous awards, such as the CEMEX Building Award (2011 and 2013), the Kunstpries Berlin 2012 for her career by the Akademie der Künste, two silver medals at the Mexican Biennial of Architecture, and the Global Award for Sustainable Architecture by the LOCUS Foundation, Cité de l´Architecture, Paris (2014). Her work is included in the collections of major museums, such as the Centre Pompidou, the Carnegie Museum of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago.

She has lectured at many schools and institutions around the world. She has been the Louis Kahn Visiting Professor at Yale (Spring 2015), the Cullinan Visiting Professor at Rice (Spring 2016), and Adjunct Associate Professor of Architecture at Columbia (Fall 2016), where she currently (Spring 2017) holds the Norman R. Foster Professorship of Architectural Design. E-mail: info@tatianabilbao.com; press@tatianabilbao.com

Nuria Benítez graduated in architecture with honors from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in 2013, after studying for a year at the L'École National Supérieure d'Architecture Paris-Belleville. She has collaborated with the Architecture Faculty Editorial Team at UNAM, and on an interdisciplinary research housing project CASA-UNAM. In 2014 she worked for the exhibition "Latin America in Construction: Architecture 1955-1980" at the MOMA, New York. Nuria has been with Tatiana Bilbao Estudio since 2015 and maintains also an independent practice. Email: n.benitez@tatianabilbao.com