Professor in Residence, Department of Architecture, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

This study uses the “urban water commons” lens to examine the intricate interplay between urban informality and bodies of water. Case studies from Jakarta, Beirut, Medellín, and Dhaka are analyzed, each illuminating a unique array of challenges. Themes of environmental degradation, involuntary displacement, and infrastructural deficits are prevalent across these urban contexts. The paper stresses the urgent need for comprehensive urban planning strategies that safeguard equitable access to and shared stewardship of urban water resources. It underscores the necessity of government policies that prioritize community involvement, environmental sustainability, and the integration of informal settlements into the wider urban fabric.

Urban informality, a complex and pervasive phenomenon, has emerged as an integral part of urban landscapes across the globe. Informality manifests in a wide array of activities, transactions, and structures that operate outside the sphere of formal governance and regulation. A myriad of intertwined factors, such as rapid urbanization, entrenched economic disparities, policy inadequacies, and the scarcity of affordable housing options, have contributed to the propagation of informality, making it a significant facet of contemporary urban realities.

Simultaneously, rivers, often threading through these informal urban spaces, serve as pivotal components of the urban ecosystem. They function as sources of water, routes of transportation, and providers of livelihoods, while also bearing the brunt of waste disposal. Frequently, due to factors like availability and affordability of land, as well as water accessibility, informal settlements materialize along these riverbanks. Yet, this adjacency to rivers brings with it an array of challenges, including an increased risk of flooding, environmental pollution, and threats of eviction due to land disputes.

In the quest to better comprehend the intricate interplay between urban informality and rivers, this paper invokes the concept of “urban water commons.” Through this perspective, the study underscores the importance of crafting urban policies and strategies that respect and reinforce the principles of the commons, providing equitable access and shared stewardship of our urban water resources.

Pivoting on this, the subsequent sections of this manuscript delve into an investigation of four discrete aspects, each intricately linked to the intersectionality between urban informality and rivers perceived as urban water commons. Each aspect, drawn into focus through a selected case study, brings to light a distinctive array of issues and implications, thereby enhancing our comprehension of this complex interplay. The facets under examination encompass the frictions borne out of competing interests in formal and informal developments along waterfronts, the efficacy of flood mitigation strategies in informal settlements, the societal repercussions of classifying rivers as “no man’s land,” and the potential of rivers in offsetting the deficit of public spaces within informal settlements. The rigorous analysis of these facets forms the keystone of this study, facilitating a nuanced understanding of the multifarious interactions between urban informality and water commons.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Urban Informality

The discourse on urban informality has evolved since the seminal work on the “informal sector” by Keith Hart in the 1970s.1 Initially, urban activities were categorized into formal and informal sectors, but this binary classification has been critiqued by scholars who advocate for a more nuanced understanding that transcends rigid categorizations. Informality is now recognized as a ubiquitous urban process, challenging the inflexible boundaries between formal and informal urban realities.2

Scholars have explored the multifaceted socio-economic dimensions of urban informality. Some link it to poverty and livelihoods and others like De Soto asserts that under favorable conditions, informality can also serve as a pathway out of poverty.3 Recent scholarship has offered a more nuanced view of urban informality, considering it as a diverse range of behaviors and practices operating outside formal institutional regulations within urban environments.4

Moving beyond simplistic categorizations, scholars advocate for a comprehensive understanding of urban formation and urbanization, recognizing informality as a deliberate strategy with the state playing various roles in enabling, regulating, or promoting it.5 Embracing informality’s resilience, innovation, and adaptability is crucial for inclusive and sustainable urban development.6 Therefore, acknowledging the nuanced nature of urban informality and transcending rigid classifications can pave the way for a more equitable urban future.7

Urban Commons

The scope of the commons, initially centralized around the management of natural resources by the seminal work of Ostrom and Hardin,8 has witnessed significant expansion to incorporate the concept of urban commons. These urban commons cannot be reduced to physical assets exploited within urban terrains; instead, they materialize through collective action and symbolic processes that metamorphose urban space.9

In this tapestry of urban commons, cities emerge as incubators, nurturing varied forms of commons, from squares and public space to community gardens, and housing.10 These multifaceted forms of commons also encompass the critical domain of urban water, evolving through complex interactions between human and natural systems and profoundly influencing urban livelihoods and ecosystems.

While operating within an urban environment predominantly shaped by the dynamics of state and market, urban commoners actively participate in “commoning,” a practice aimed at collectively governing the resources necessary for their survival.11 This practice of commoning is intimately linked to the creation of urban commons, embodying a community-centric dimension within the broader state-market dynamics. When we incorporate this understanding into the concept of urban water commons, we gain insights into how communities, even within the constructs of state and market influences, can collectively manage and govern crucial resources like water. This broadens the scope of urban commons, illuminating the convergence of political-economic structures, resource management, and community practices.

To summarize, the discourse on urban informality and the concept of urban commons provides valuable lenses through which to understand the complexities of urban spaces. Urban informality challenges traditional binary categorizations and recognizes the intertwined nature of formal and informal urban realities. It encompasses diverse behaviors and practices shaped by socio-economic inequalities and poverty, yet also possesses the potential for resilience, innovation, and adaptability. On the other hand, the notion of urban commons expands the understanding of collective action and symbolic processes in shaping urban space, encompassing resources beyond physical assets. By linking these concepts, we recognize the potential for communities, within the dynamics of state and market influences, to collectively govern crucial resources like water. The convergence of informality and urban commons highlights the significance of community-centered approaches and collective agency in shaping sustainable and equitable resource management in urban areas. This holistic perspective deepens our understanding of the interconnectedness between urban informality, urban commons, and the socio-economic dynamics of urban environments.

METHODOLOGY

The methodology for this study is anchored in a qualitative research approach, designed to capture the multifaceted interplay between urban informality and water commons. The study draws on four diverse case studies – Jakarta, Beirut, Medellín, and Dhaka – to provide a comprehensive perspective. The multiplicity of geographical and cultural contexts furnished by these case studies allows for a nuanced, cross-comparative analysis.

A range of qualitative research tools were employed for data collection, encompassing semi-structured interviews, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) mapping, and the accumulation of satellite and photographic imagery. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with a diverse set of stakeholders, encompassing government officials, urban planners, and inhabitants of the informal settlements, providing an in-depth view of the local dynamics. GIS mapping served as a valuable tool for visualizing and assessing the spatial interconnections between informal settlements and their adjacent water bodies. Complementing these methods, the study utilized satellite and photographic imagery to capture and trace the physical transformations and conditions within the settlements over time.

COMPETING INTERESTS: EXPLORING FORMAL AND INFORMAL DEVELOPMENTS ALONG WATERFRONTS

The proximity of informal neighborhoods to bodies of water, coupled with their central location within urban cores, makes them attractive lands for development, leading to competing interests between formal and informal approaches. This interplay is exemplified by the case of the Korail informal settlement in Dhaka city.

Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, experiences a high population density and low sea level, with a significant portion of the population living below the poverty level. Many residents have migrated from rural areas, seeking economic opportunities in the city. Climate migration further contributes to population growth, with thousands of people flocking to Dhaka on a daily basis. Consequently, the demand for housing intensifies, prompting the emergence of slums as a prevalent settlement option due to limited government resources and support.

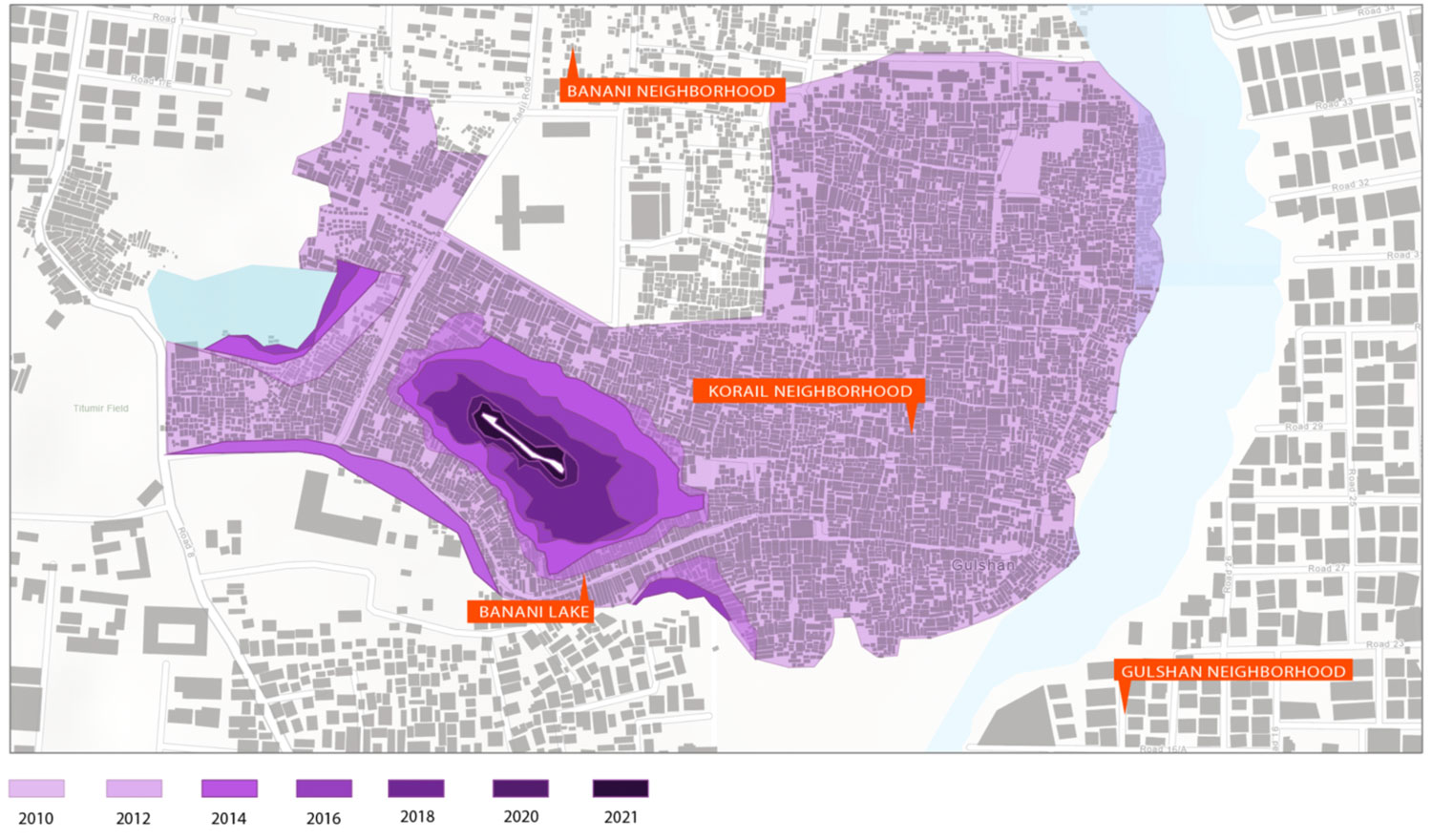

One such slum is Korail, spanning approximately 110 acres [44.5 ha] and accommodating around 200,000 residents (Fig. 1).12 Korail is accessible by road from affluent neighboring areas, such as Banani, Gulshan, and Mohakhali, known for their upscale residential and commercial developments. Additionally, the Banani Lake intersects the southern and eastern parts of Korail, offering another means of access. The local economy predominantly thrives on informal activities, including garment factory work, rickshaw pulling, street hawking, and provision of services to nearby neighborhoods like Gulshan and Banani.

The Korail area initially had a private tenure and was designated for the Department of Telegraph and Telephone Board of Bangladesh (T&T).13 In the 1990s, part of the land was given to the Public Works Division (PWD), and people illegally captured unoccupied lands. These lands were rented out and sometimes sold to low-income people who became occupants of Korail. The expansion of Korail onto the Banani Lake has been driven by overpopulation resulting from climate migration and the scarcity of available urban land. Consequently, informal dwellings now cover the entire lake, further expanding the boundaries of the slum (Fig. 2).

This encroachment has been facilitated by waste dumping and the continuous influx of people. With limited open spaces available, social interactions primarily occur in bustling bazaars, tea stalls, stores, and the narrow alleyways and courtyards that characterize the settlement.

Unfortunately, overpopulation and the lack of formal infrastructure have led to adverse conditions for the Banani Lake, compromising its ecological health and creating an unhealthy environment for the residents of Korail and beyond. Addressing the scarcity of public spaces and mitigating water pollution requires the provision of formal infrastructure within Korail. Moreover, revitalizing the lake as a communal space holds potential for enhancing the quality of life for the community. However, the government’s development plans for Korail diverge from these considerations. Instead, they aim to construct an Information and Communication Technology (ICT) village, which would involve resettlements. These plans primarily serve the needs of adjacent high-priced neighborhoods and seek to stimulate economic growth. The government’s vision for Korail aligns with a broader master plan for Dhaka’s development, envisioning green corridors, public parks, and repurposing of specific sites, as outlined by RAJUK, a key capital development authority.14

While the informal development on the lake is a response to the scarcity of available land for housing, the government’s development aspirations tend to favor privileged communities and speculative market interests. As a result, there is a disconnection between the grassroots dynamics of informal settlements and the formal development plans pursued by the government. This misalignment hinders comprehensive planning and considerations for the future of informal settlements, their relationship with the lake as a space of commons, and the equitable distribution of resources and amenities. The competing interests between formal and informal developments along waterfronts necessitate a balanced approach that takes into account the needs and aspirations of the marginalized communities residing in informal settlements.

FLOOD MITIGATION STRATEGIES IN INFORMAL SETTELEMENTS: ASSESSING EFFICACY AND IMPLICATIONS

The interplay between informal settlement communities and their common blue spaces in Eastern South Asia is significantly affected by frequent flooding issues. Unfortunately, governmental efforts to address these concerns often fall short and inadvertently disrupt the livelihoods of the communities involved. This phenomenon is readily observable in Jakarta, Indonesia’s bustling hub for the finance and service industries since the nation’s independence in 1945.

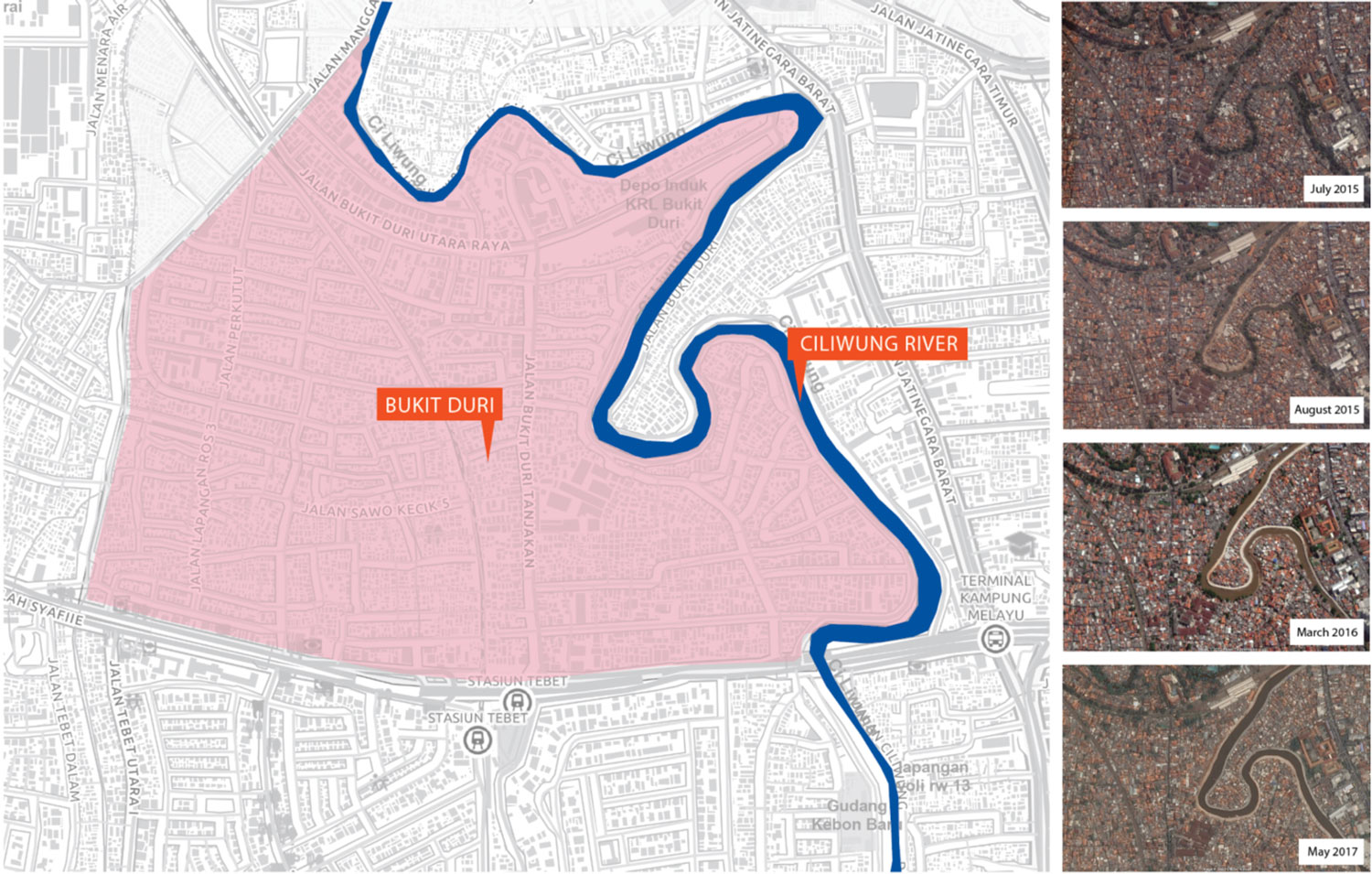

In the 1970s, an oil-fueled economy spurred population growth in Jakarta, drawing migrants from various regions. The lack of affordable government-provided housing led these underprivileged individuals to settle in informal areas such as Bukit Duri. Positioned between a railway line and the Ciliwung River, Bukit Duri is one of the city’s most densely populated informal settlements.

Jakarta is intersected by thirteen rivers, with the Ciliwung spanning 119 kilometers. This waterway, unfortunately, suffers from severe pollution and is prone to flooding during the year’s early months. Jakarta’s most devastating flood occurred in 2007 due to heavy rain and waterways clogged with debris, which submerged nearly half of the city. These floods disproportionately affect Jakarta’s informal settlements or kampungs, home to an estimated 350,000 residents living along the riverbanks.15 In the 2007 flooding, Bukit Duri was particularly affected, with water levels reaching up to five meters and persisting for fifteen days.16

To address flooding, the government often resorts to evicting and resettling communities in these informal settlements. During Joko Widodo’s governorship, with the involvement of Ciliwung Meredeka NGO and architecture bureau Studio Akanoma, a proposal was put forward to construct elevated 4-10 story housing units, creating space for socio-economic activities. However, this plan was shelved with the change of governorship to Basuki Purnama, resulting in the reclassification of the riverbanks as illegal, leading to subsequent demolitions and evictions.

Forced evictions in Jakarta are unfortunately not a new phenomenon and occur for various reasons, including slum upgrading, development, illegal occupation, lack of tenure, infrastructure building, and beautification. According to a 2006 report by Human Rights Watch titled “Condemned Communities – Forced Evictions in Jakarta,” fourteen instances of forced evictions were recorded under Governor Sutiyoso’s administration in 2006.17 In Bukit Duri’s case, a 15-meter distance was established from the riverbank, leading to the eviction of all residents within that line and the demolition of all structures on both embankments, replaced by a floodwall and a 10-meter wide “inspection road” (Fig. 3).18

This road has created a significant barrier between the community and the river, disrupting their access to the water. Moreover, during heavy rains, the floodwall proves insufficient, failing to solve the flooding problem. During this process, evictions were executed without compensation or community consultation, with military forces sometimes employed to quell resistance. In the end, approximately 163 households were relocated to Rusunawa Cipinang Besar Selatan and Pulo Gebang.19

The Bukit Duri case demonstrates a poorly executed resettlement process, leading to a prevailing sentiment among community members that flood control was merely an excuse for eviction. Furthermore, for those who have not been resettled, the floodwall and road have effectively blocked access to the common blue space. This situation underscores the need for more thoughtful, community-inclusive strategies in addressing the complex interplay between informal settlements and their shared blue spaces.

SOCIETAL REPERCUSSIONS: CLASSIFYING RIVERS AS ‘NO MAN’S LAND’ IN URBAN CONTEXT

The management of urban land, particularly in relation to natural resources like rivers, is vital for the sustainable growth of cities. Formal development strategies adopted by governments often influence how these spaces are managed and utilized. A striking example of this is seen in the neighborhood of Bourj Hammoud and its relationship with the Beirut River in Lebanon.

The Beirut River has been significant in the history of Bourj Hammoud, a densely populated urban area in Beirut. The neighborhood’s origins trace back to World War I when it served as a refuge for Armenian immigrants who settled on the river’s eastern bank. Since then, the river has acted as both a physical boundary and an important environmental resource.

However, in recent years, the Beirut River has been subjected to serious neglect and mismanagement. Despite its critical role in the local ecosystem, the river has become a dumping ground for industrial waste and household sewage. This, coupled with large variations in river flow between the wet and dry seasons, has resulted in significant environmental challenges.

One of the major transformations for the Beirut River has been its canalization, an effort to control flooding.20 Paradoxically, this measure has led to a greater disconnect between the river and the people. The canal acts as a barrier, severing Bourj Hammoud from central Beirut and creating a socio-spatial divide. Many local residents are unaware of the river due to this physical disconnection.

Government policies have further exacerbated the situation, effectively treating the river as “No Man’s Land.” A notable example is the Beirut River Solar Snake Project launched by the Ministry of Energy and Water in 2013 (Fig. 4). The project involved installing solar panels over the river, converting it into a renewable energy source. While the initiative creatively addresses the city’s energy needs, it further distances the river from its urban surroundings.

In Bourj Hammoud, where public spaces and green areas are scarce, the implications of such policies are significant. The transformation of the river for energy production further deprives the community of potential recreational and aesthetic benefits that a well-maintained river could offer. A memorial built near the river edge remains underutilized due to the physical disconnection from the river.

The case of Bourj Hammoud and the Beirut River demonstrates how formal development strategies can impact the management of urban land and natural resources. It underscores the necessity for sustainable and inclusive urban planning that integrates, rather than isolates, natural resources from the urban context. The future societal and environmental health of urban communities depends on the reimagining and reclaiming of such spaces.

LEVERAGING RIVERS AS PUBLIC SPACES: ADDRESSING DEFICITS WITHIN INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS

The rivers coursing through cities of the Global South are frequently beset by pollution, often stemming from industrial waste and inadequate sanitation within informal settlements. This pollution diminishes the potential of the rivers to serve as public recreational spaces, especially within disadvantaged communities. This pattern is notably evident in Medellín’s informal neighborhood, Santa Cruz, situated within Comuna 2.

Medellín’s landscape is characterized by sixteen comunas, informal settlements perched on the city’s valley slopes, which face particular challenges in harnessing the potential of the city’s 104-kilometer river as a public amenity. These hurdles encompass issues of pollution, safety, and limited accessibility to riverside public spaces. The canalization and straightening of the Medellín River, initiated in 1912 and culminating with the metro system’s construction in 1985, led to the restoration of certain river sections and the erection of new bridges.21

The city’s population explosion in the 1980s led to a surge in urban informality, with illegal developments particularly concentrated in the northern parts of the city. In response to this, Mayor Sergio Fajardo introduced several urban intervention initiatives in 2004, aimed at integrating informal neighborhoods into the city’s metro line. This innovative metro cable system extended public transit services into the city’s informal settlements, thereby facilitating community access to key amenities such as schools, recreation centers, and libraries.

Despite these advancements, river accessibility remains limited with few dedicated public use spaces. This is especially the case within Comuna 2’s Santa Cruz neighborhood, which lacks safe paths to the riverside, and where community spaces are scant due to high-density living. The potential, however, for the creation of riparian ecology and public green spaces along the river is immense.

River pollution, a recurrent issue within Santa Cruz, emanates from eleven creeks serving as waste disposal sites (Fig. 5). Consequently, both the Medellín River and its tributaries are severely contaminated. This has led to a unique housing typology, where houses adjacent to the creeks turn their backs to the water bodies, avoiding the malodorous pollution from the garbage and sewer waste. The creek’s channelization interrupts vehicular and pedestrian access, creating a sense of isolation from the city.

Thus, while the residents of these comunas grapple with a shortage of public spaces, they simultaneously face the threats posed by flooding and pollution due to their proximity to the river. Instead of reaping the communal benefits that these river spaces could offer, these communities are burdened with the hazards that come with their location.

CONCLUSION

The exploration of four distinct case studies – Jakarta, Indonesia; Beirut, Lebanon; Medellín, Colombia; and Dhaka, Bangladesh – sheds light on the intricate dynamics between informal settlements and their shared blue spaces, such as rivers and lakes. Each case carries unique circumstances and challenges, but common threads of environmental degradation, forced evictions, and infrastructural mismanagement interweave these narratives, underscoring a global trend with local implications.

In Jakarta, the recurrent floods disproportionately affect informal settlements like Bukit Duri, which is caught in a cycle of evictions and failed flood mitigation strategies. The government’s reaction to these issues has often resulted in disruption rather than solution, inadvertently severing the community’s connection to their shared water space. Similarly, in Dhaka’s Korail slum, overpopulation driven by climate migration and the scarcity of available urban land have led to significant ecological strain on Banani Lake. However, formal development aspirations that tend to favor privileged communities and speculative market interests have impeded the provision of much-needed infrastructure and the revitalization of the lake as a communal space.

The cases of Beirut and Medellín further illustrate how infrastructural development and government policies can inadvertently create a socio-spatial divide. In Beirut, the canalization of the river and the installation of solar panels have distanced the river from its urban surroundings, depriving the community of potential recreational and aesthetic benefits. Meanwhile, in Medellín, despite advancements in public transit services to integrate informal neighborhoods, river accessibility remains limited, and communities face threats from pollution and flooding.

Each of these cases underscores the necessity of developing thoughtful, inclusive, and sustainable urban planning strategies that consider the needs and aspirations of marginalized communities. Rather than treating rivers and lakes as barriers or dumping grounds, these bodies of water should be seen as vital communal spaces that can enhance the quality of life within informal settlements.

Effective government policies and urban development plans need to center community participation in decision-making processes, ensuring evictions or relocations are a last resort with support systems to minimize livelihood disruptions. Environmental sustainability should be a cornerstone, addressing pollution, preserving blue spaces, and creating green spaces to boost settlements’ resilience. Further integration into the broader urban fabric through improved transport links and amenities can help bridge the socio-spatial divide. As highlighted by these cities’ experiences, the health and future of urban communities in the Global South greatly hinge on innovative, equitable solutions that reimagine and reclaim shared blue spaces as vital urban life elements.

References

Adri, Neelopal and David Simon. “A Tale of Two Groups: Focusing on the Differential Vulnerability of ‘Climate-Induced’ and ‘Non-climate-Induced’ Migrants in Dhaka City.”

Climate and Development 10, no. 4 (2018): 321–36 – doi:10.1080/17565529.2017.1291402.

AlSayyad, Nezar. “Urban Informality as a ‘New’ Way of Life.” Environment and Urbanization 16, no. 2 (2004): 43-57.

Borch, Christian, and Martin Kornberger. 2015. Urban Commons: Rethinking the City.

Abingdon, Oxon, UK and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

De Angelis, Massimo, and Stavros Stavrides. “Beyond Markets or States: Commoning as Collective Practice (A Public Interview).” An Architektur 23 (2010): 3-2.

De Soto, Hernando. The Other Path: The Invisible Revolution in the Third World. New York: Harper & Row, 1989.

Dovey, Kim, Brian Cook, and Amanda Achmadi. “Contested Riverscapes in Jakarta: Flooding, Forced Eviction and Urban Image.” Space & Polity 23 (3): 265–82 - doi: 10.1080/13562576.2019.1667764.

Echeverri Restrepo, Alejandro et al. Medellín: Environment, Urbanism and Society, translated by Eduardo Cárdenas and Daniel Hawkin. Edited by Michel Hermelin, Alejandro Echeverri Restrepo, and Jorge Giraldo Ramírez. Medellín, Col.: Fondo Editorial Universidad EAFIT, 2012.

Eidelman, Talia A., and Sarai Safransky. “The Urban Commons: A Keyword Essay.” Urban Geography 42, no. 6 (2021): 792-811.

Frem, Sandra. “Nahr Beirut: Projections on an Infrastructural Landscape.” PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Architecture, 2009.

Gidwani, Vinay, and Amita Baviskar. “Urban Commons.” Economic and Political Weekly 46, no. 50 (2011): 42-43.

Gillespie, Tim. “From Quiet to Bold Encroachment: Contesting Dispossession in Accra’s Informal Sector.” Urban Geography 38, no. 7 (2017): 974-92.

Hardin, Garrett. “The tragedy of the commons.” Science 162, no. 3859 (1968): 1243-48.

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. Commonwealth. Cambridge MA, USA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Hart, Keith. “Informal Income Opportunities and Urban Employment in Ghana.” Journal of Modern African Studies 11, no. 1 (1973): 61-89.

McFarlane, C. “Rethinking Informal Urbanism.” Progress in Human Geography 36, no. 4 (2012): 403-20.

Ostrom, Elinor. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action.

Cambridge MA, USA: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Roy, Ananya. “Urban Informality: Toward an Epistemology of Planning.” Journal of the American Planning Association 71, no. 2 (2005): 147-58.

Stavrides, Stavros. Common Space: The City as Commons. London: Zed Books, 2016.

Sultana, Razia, Thomas Birtchnell, and Nicholas Gill. “Urban Greening and MobilityJustice in Dhaka’s Informal Settlements.” Mobilities 15, no. 2 (2020): 273-89 – doi: 10.1080/17450101.2020.1713567.

Widyaningsih, Anastasia, and Pieter Van den Broeck. “Social Innovation in Times of Flood and Eviction Crisis: The Making and Unmaking of Homes in the Ciliwung Riverbank, Jakarta.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 42, no. 2 (2021): 325-45 – doi: 10.1111/sjtg.12370.

Keith Hart, “Informal Income Opportunities and Urban Employment in Ghana,” Journal of Modern African Studies 11, no. 1 (1973): 61–89.

Nezar AlSayyad, “Urban Informality as a ‘New’ Way of Life,” Environment and Urbanization 16, no. 2 (2004): 43-57; C. McFarlane, “Rethinking Informal Ubanism,” Progress in Human Geography 36, no. 4 (2012): 403-20.

Hernando De Soto, The Other Path: The Invisible Revolution in the Third World (New York: Harper & Row, 1989).

J. A. Aramburu Guevara, “The Different Meanings of Informality: The Case of Housing in Mexico City,” Urban Geography 35, no. 4 (2014): 543-61.

Ananya Roy, “Urban Informality: Toward an Epistemology of Planning,” Journal of the American Planning Association 71, no. 2 (2005): 147-58.

Alan Gilbert, “On the Mystery of Capital and the Myths of Hernando de Soto: What Difference Does Legal Title Make?” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 26, no. 2 (2002): 389-404.

Roy, “Urban informality.”

Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge MA, USA and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990); Garrett Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Science 162, no. 3859 (1968): 1243-48.

Vinay Gidwani and Amita Baviskar, “Urban Commons,” Economic and Political Weekly 46, no. 50 (2011): 42-43.

Stavros Stavrides, Common Space: The City as Commons (London: Zed Books, 2016); Tim Gillespie, “From Quiet to Bold Encroachment: Contesting Dispossession in Accra’s Informal Sector,” Urban Geography 38, no. 7 (2017): 974-92; Eric Eizenberg, “Actually Existing Commons: Three Moments of Space of Community Gardens in New York City,” Antipode 44, no. 3 (2012): 764-82; Christian Borch and Martin Kornberger, Urban Commons: Rethinking the City (Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2015); Talia A. Eidelman and Sarai Safransky, “The Urban Commons: A Keyword Essay,” Urban Geography 42, no. 6 (2021): 792-811; Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Commonwealth (Cambridge MA, USA: Harvard University Press, 2009); Massimo De Angelis and Stavros Stavrides, “Beyond Markets or States: Commoning as Collective Practice (A Public Interview),” An Architektur, e-flux, 17.

Amanda Huron, Carving Out the Commons: Tenant Organizing and Housing Cooperatives in Washington DC, vol. 2 (Minneapolis MN, USA: University of Minnesota Press, 2018) – doi: 10.5749/j.ctt2121778.

Neelopal Adri and David Simon, “A Tale of Two Groups: Focusing on the Differential Vulnerability of ‘Climate-Induced’ and ‘Non-climate-Induced’ Migrants in Dhaka City,” Climate and Development 10, no. 4 (2018): 321-36 – doi: 10.1080/17565529.2017.1291402.

Sanjida Ahmed Sinthia, “Development Measures for Slums of Dhaka City: Case Study Area Korail Slum,” The Iraqi Journal of Architecture and Planning 20, no. 1 (2021): 42-55 – doi: 10.36041/iqjap.2021.169085.

Razia Sultana, Thomas Birtchnell, and Nicholas Gill, “Urban Greening and Mobility Justice in Dhaka’s Informal Settlements,” Mobilities 15, no. 2 (2020): 273-89 – doi: 10.1080/17450101.2020.1713567.

Rita Padawangi et al., “Mapping an Alternative Community River: The Case of the Ciliwung,” Sustainable Cities and Society 20 (2016): 147-57 - doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2015.09.001.

Wonka Mone, “Vulnerability Assessment and Coping Mechanism Related to Floods in Urban Areas: A Community-Based Case Study in Kampung Melayu, Indonesia” (Master of Science thesis, Gadjah Mada University, 2008).

Arie Afriansyah, “For the Many, Not the Few: Case Analysis of Bukit Duri Forced Eviction in Jakarta,” Rechtsidee, Law Journal 4, no. 2 (2018) – doi: 10.21070/jihr.v4i2.43.

Kim Dovey, Brian Cook, and Amanda Achmadi, “Contested Riverscapes in Jakarta: Flooding, Forced Eviction and Urban Image,” Space & Polity 23, no. 3 (2019): 265-82 – doi: 10.1080/13562576.2019.1667764.

Anastasia Widyaningsih and Pieter Van den Broeck, “Social Innovation in Times of Flood and Eviction Crisis: The Making and Unmaking of Homes in the Ciliwung Riverbank, Jakarta,” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 42, no. 2 (2021): 325-45 – doi: 10.1111/sjtg.12370.

Sandra Frem, “Nahr Beirut: Projections on an Infrastructural Landscape” (PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Architecture, 2009).

Alejandro Echeverri Restrepo et al., Medellín: Environment, Urbanism and Society, trans. Eduardo Cárdenas and Daniel Hawkin, eds. Michel Hermelin, Alejandro Echeverri Restrepo, and Jorge Giraldo Ramírez (Medellín, Col.: Fondo Editorial Universidad EAFIT, 2012).

Figure 1: photo by © Aditya Kabir.

Figures 2-5: photos by © the Author

Taraneh Meshkani is an Assistant Professor of Architecture at Kent State University’s College of Architecture & Environmental Design, and the Senior Editor of The Plan Journal. She holds a doctoral degree from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. As a former editorial board member of New Geographies Journal and the co-editor in-chief of Geographies of Information, Meshkani’s work explores the intersection of spatial inequalities and conflict with socio-political and environmental issues. Through her research, she sheds light on the impact of the built environment on marginalized communities and explores strategies for addressing these inequalities. E-mail: tmeshkan@kent.edu