Professor in Residence, Department of Architecture, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

For more than 20 years, Rachel Whiteread has situated her sculpture inside the realm of architecture. Her constructions elicit a connection between: things and space, matter and memory, assemblage and wholeness by drawing us toward a reciprocal relationship between objects and their settings. Her chosen means of casting solids from “ready-made” objects reflect a process of visual estrangement that is dependent on the original artifact. The space beneath a table, the volume of a water tank, or the hollow undersides of a porcelain sink serve as examples of a technique that aligns objet-trouvé with a reverence for the everyday. The products of this method, now rendered as space, acquire their own autonomous presence as the formwork of things is replaced by space as it solidifies and congeals. The effect is both reliant and independent, familiar yet strange. Much of the writing about Whiteread’s work occurs in the form of art criticism and exhibition reviews. Her work is frequently under scrutiny, fueled by the popular press and those holding strict values and expectations of public art. Little is mentioned of the architectural relevance of her process, though her more controversial pieces are derived from buildings themselves – e,g, the casting of surfaces (Floor, 1995), rooms (Ghost, 1990 and The Nameless Library, 2000), or entire buildings (House, 1993). From an architect’s perspective, Whiteread offers an unsettling interpretation of architectural space, one that is dependent on filling space to the brim, barring life from entering or holding it in suspended animation from within. This paper argues that architectural form, whether fashioned from contingencies or autonomous acts, has reached a saturation point in architectural criticism. The work of Whiteread helps forge an alternative reading that embraces the object-oriented methods inherent in design by turning the tables on our fascination of figural form and the obsession of substance. The essay analyzes several of Whiteread’s projects in order to explain the meaning and techniques of her work, and places them within the context of Luigi Moretti’s 1953 essay on the “Structures and Sequences of Spaces.” It concludes with research work that attempts to use Whiteread’s method to better understand the figural and material attributes of architectural space.

The object is again under scrutiny in the realm of architecture. As educators and designers we have made it the “object of focus” as we help others, and ourselves, decipher how to observe, interpret, analyze, write, and design. As architects we are drawn to the object’s power to attract and repulse, to inspire the sublime or to inflict alternate conditions by influence. From Luis Buñuel’s tragically romantic “obscure object of desire” to Heidegger’s rumination on the nature of “things,” the fetish of objects continues to lie squarely in the path of architecture.

Exercises by Peter Eisenman brought us to appreciate the internalization of the architectural object, an attractive play of form and syntax on architecture’s own terms – perhaps the closest definition of autonomy that we have. The response: an era of design when architecture, landscape, and urbanism aspired to find sources in localities, contextual clues, existing practices, and interdisciplinary concerns, as in the work of Ian McHarg, Jane Jacobs, Kenneth Frampton and Vittorio Gregotti.

Our current situation, in the undertow of computational tools, promises an alternative view of objects: an appreciation of nucleic things, particulate matter composed of simple forms with rules that generate, randomize, mutate, and/or optimize architectural space. In this instance objects, like cells, are semi-autonomous, adapting in either positive or negative ways as they populate specific contexts or environments. Absent of hierarchy, these objects present themselves as elements, primitives or pixels. They steer clear of ranked order and privilege local interactions, accretions, or filling voids to meet the needs of a system of emerging form. Any claim to orders of importance may be taken as a sign of autonomous malevolence or a view that favors top-down measures.

The question of architecture’s objecthood is a tricky one. Indeed, what often starts as a movement of rootedness and contingent goodwill can grow to be redundant, over-used, or worse, over-valued – all signs of growing autonomy. As new interpretations take to the stage, the debate is certain to continue.

Space as Object

Rachel Whiteread’s sculptural work from the late-1980s to 2000 helps us trace the status of architecture as an object-making discourse. Whiteread’s approach to art suggests an infatuation with objects but also with space. Her castings create an impression of not only everyday things but also of the space around them, more precisely, the space that remains after the outer shell is peeled away.

The choice of everyday objects as a source for sculpture leaves familiar yet foreign impressions on our perception and memory. By using normative objects for these casting events, Whiteread aligns herself within the objet-trouvé traditions of Paolozzi, Duchamp, Beuys, and Johns, yet departs from this methodology by offering objects as surrogates, impressions that deny any material significance embodied by the found object in favor of a more neutral, often white, substitution. This neutral interpretation provides a means to inspect the spatial condition of the object, representing the atmosphere that thinly adheres to its surface, a type of outer coating that has been lifted from it. Whiteread often writes about the memory and provocations these objects inspire, reaching especially to objects from her childhood. These motives are common to modern art, where artistic inspiration frequently reflects life experiences. A closer reading however suggests a more nuanced approach for Whiteread, one that may help us know the dynamics of architectural space through static things.

Three Impressions

Whiteread’s objects leave impressions on us in three ways: 1) her castings maintain close affinity with the use and function of the original object, 2) the resulting sculpture often draws our attention to unseen traits of the original object, and 3) the work of art can be rhetorical, asking us to make sense of it within the context that it is situated or to form an opinion about a specific cultural condition.

The first impression of Whiteread’s sculpture involves its operation within the capacities of the original object. The instrumentality of the object’s function is transferred to the casting: the space from the underside of a table becomes a table surface or plinth; the complementary casting of a four-legged stool becomes a seat. The casting of a clawfoot bathtub results in a similar vessel that may contain water (e.g., the volume of the tub becomes the bath). There thus remains a double function to the artistic object, which retains a shadow of its use. We see this also in the design of furniture by Charles and Ray Eames. For example Ray Eames’s 1960 solid walnut stool for the Time-Life Building lobby in New York is a monolithic piece spun on a lathe from a single piece of wood and, like Whiteread’s work, is marked by strong Gestalt lines between the profile of its shape and the space that surrounds it. On first balance these objects cast doubt over what their original uses might be. Are they art or furniture, a machine part removed from its context, or …? In what way do these objects come to our consciousness as useful things, and is this playful state of recognition part of Whiteread’s intention for us as viewers? Our first impression of an autonomous sculptural object becomes a recognition then of a useful piece of furniture, a latent meaning of the object that emerges after a debate about its use.

The second reading encompassing an object’s form is less evident. This occurs when voids and crevices are exposed: the bottom of a porcelain sink or the space re-presented from the firebox of a coal-burning fireplace. The resulting objects in this instance reveal the process of their making: sand casting patterns and original production molds are brought to life in the reversal process, exposing an inquiry about the value or meaning of everyday things through re-contextualized form. These objects are like hands covered by gloves, a version of the body that is offered again in a different context (hand protection or perhaps elegant evening attire!). The notion of objet-trouvé or Duchamp’s “ready-mades” from the 1950s is in full play as art embraces ironies and inconsistencies that kick back contradictions from dispassionate white sculptural form.

The last application of Whiteread’s work is more pointed. In this instance the artist taps popular or political subjects that force a reading that is controversial or provocative. Some of these approaches are ironic, while others take clues from material culture – an alignment of associative imagery with popular tastes, recalling familiar iconography. For example, Whiteread’s 2000 Vienna Holocaust Memorial recalls 1930s Nazi German/Austrian public book burnings. The nature of the memorial – a concrete cast room where the textured edges and pages of books become the outward texture and surface of the monument function to present a traditional memorial that Adolf Loos would describe as art’s ability “to shake people from their lethargy.” 1 This work challenges our norms and expectations by drawing upon our memories while expanding our thinking (Fig. 3).

In contrast to the traditional art piece, Whiteread’s Embankment project in the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern operates on a different rhetorical level. As part of a temporary art program, the 2005 installation challenged the artist to control the 35-meter high x 152-meter long space by installing space itself. An array of cardboard boxes of differing sizes were used to cast 14,000 polyethylene forms that alter the light and density of the vast hall. Whiteread’s study of luminance of the vast 115 foot high space also remarks on how she thought simple paper boxes symbolize the use of natural resources, global and economic trade, as well as improvised shelters for the homeless amongst other commentaries (Fig. 4).

Anti-Architecture

Given this analysis of Whiteread’s work, we could position her as the anti-architect, building space by liberating it from the surfaces of the architectural context. Still, while her work is autonomous once formwork is removed, it remains dependent on the form-making surface for its expression and life. Space as object is, in itself, the objective. Architects aim to capture and tame space, but are often distracted by the seductiveness of form, material, and substance. Whiteread is more patient, she slows the speed of space as it stretches and tugs at the walls and ceilings of architecture. There is a sense of the overall volumetric configuration when we stand and see her work from a distance, yet we are rewarded also with detail, texture, and mass as we close in and approach her sculptures. In working her first architecturally scaled piece, Ghost (1990) (Figs. 1, 2), Whiteread lends us an account of this very impression. She writes:

I spent three months searching for a room in North London, very close to where I grew up. I spent about four months working in this room, casting the piece, and placing it against the wall as it was cast. I really had no sense of what it was until I relocated it in the studio. By looking at the light switch, I had suddenly realized what I had done. I had made the viewer become the wall. 2

A figure-ground reversal occurs as architecture and space are personified. In Whiteread’s work of cast transparent resin we see the potential of “becoming the wall.” In these pieces we peer through to the other side, a type of frozen space with suspended color and optical occlusions. For Water Tower (1998), Whiteread was interested in the way light passed through a cylindrical resin cast of a typical lower-Manhattan water tank. Vessel space levitating above domestic space, presented as a bright beacon and then as a vessel for pressurized plumbing, Water Tower is an example of sculpture that holds functional affinities to the original (Fig. 5). Another example using the same material strategy but employing rhetorical commentary is Monument (2001), a proposal for a temporary piece on the empty “fourth plinth” in Trafalgar Square. 3 Whiteread replicated the existing plinth in clear resin, then inverted its orientation and placed it atop the original. A “ready-made” ironic gesture in its own right leaving individuals with a sense of what it means, “to place a plinth upon a pedestal.” The rhetorical gesture underscored what contemporary art can accomplish in the public arena of British war heroes and royalty. Whiteread explains that she wanted to calm the noise and traffic of the square’s bustle by offering a distraction of form and light. But it is not hard to imagine that the position of her sculpture – in its inverted and contrary orientation – was intended to upset the masculine and military history of the British status quo. 4

The Structure of Space

In the 1952 essay, “The Structure and Sequence of Space,” Luigi Moretti argued that “empty space” in buildings, in contrast to their constructive and formal perperties, is central to understanding the nascent and full impact of the architectural experience. 5 In making this claim for complementarity between space and object, Moretti relied on the idea of space as a hollow that not only contains but houses dynamic elements that alter our interpretation and use of the spatial realm. This, Moretti claimed, is accomplished by the use of movements, compressions, entries, and exits. He assigned four principles upon which we might judge the effectiveness of the spatial interior: (1) “dimension,” or the physical quantity of the absolute volume, (2) “density,” the perceived effects based on the quantity of light entering a spatial volume, (3) “pressure” or “energetic charge,” pertaining to the relative ways that various points in space are influenced by the bounding enclosure, and (4) “quality,” which he described as analogous to the fluidity of space embodying energies that are restricted or released as they move freely within the interior.

Moretti’s notion of “empty space,” along with his description of volume as a stage for kinetic experience, can be applied to the energies in Whiteread’s castings. We see this “energetic charge” of space in context to her choice of “ready-mades,” although in Moretti’s case the environments are the ruins of Rome and the weathered surfaces of the Italian Baroque. His creation of figure/ground model reversals in plaster of Hadrian’s Villa and Guarino Guarini’s project for Santa Maria Divina Providenza in Lisbon in the 1950s were some of the first modern studies of architecture and space. With these, along with his dense prose, Moretti characterized an autonomous spatial reading of architecture not unlike Eisenman’s argument for pure architectural syntax in the 1960s and 1970s.

Figures Traveling Through Planes of Contemporary Space

Placing Moretti’s architecture and writing within the context of Whiteread’s spatial objects conjures further debate about the spatial role of architecture. The focus on space as an agent of modern architecture shares its history with the rise of Gestalt psychology and the liberation of cultural space from the stratification of Western spatial practice. Le Corbusier’s plan libre enabled a new democratic space, built on eroding the limits of spatial order with freedoms afforded by new structural principles. Wright’s preference for the horizontal confirmed a new plane for domestic space and its connection to the landscape. Both of these architects argued for the dynamic use of space, whether traveling an architectural promenade or scanning the prairie with moving eyes to spy views of the distant horizon. Modern space embraced time, motion, travel, and distances beyond.

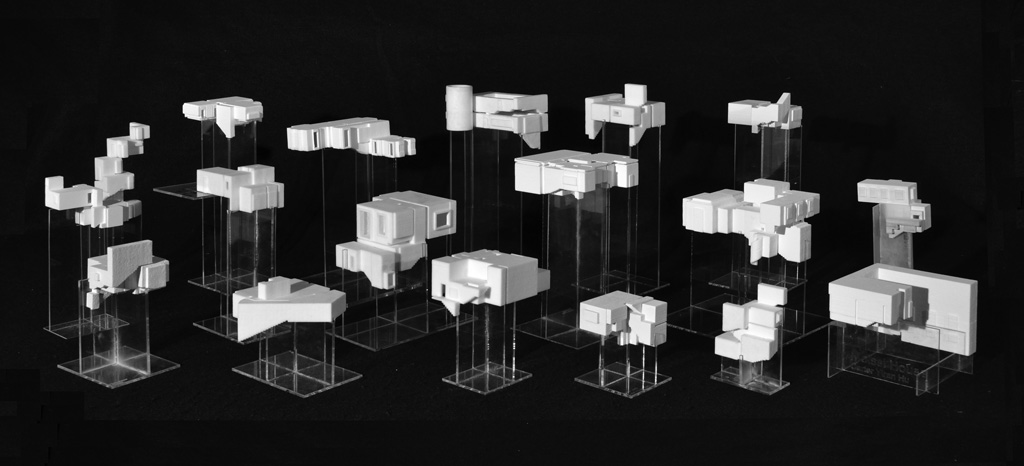

In order to understand figural space in conjunction with the architectural promenade, a team of students and myself studied and fabricated a series of Whiteread-like castings. Choosing several built and unbuilt houses by Adolf Loos, we investigated the entry sequences and social patterns of four interrelated spaces typical of his domestic work: foyer, washroom and coat alcoves, living/music rooms, and formal meal areas. The raumplan organization of the Loosian interior was chosen specifically to understand transitions through the house that occur not only as door/threshold conditions but also by way of stair ascensions and subtle floor level changes ( Figs. 6, 7, 8).

The arrangement of Loos’s rooms reflects codes and etiquettes of the social structure of the times. Many of these houses were serviced by domestic help, therefore the arrangement of interior spaces reflect strict lines of public and private. From the earliest houses to the more recent shared arrangements, demonstrate a regard for the entry sequence. Foyer spaces were frequently not grand. These opened onto larger, light-filled rooms for dispensing heavy outerwear. The equipment in these spaces tell the story of intimate domestic rituals matched to the architecture – the removal of damp coats to be hung on brass metal hooks, built-in mirror glass so guests could check their appearance before engaging the pleasantries of social exchange with hosts, etc. Often there were simple porcelain sinks to wash up at, plumbing fixtures that Loos favored and openly exhibited in these introductory spaces of the house. 6

3-D printed maquettes describe a volumetric sequence. In the raumplan these spaces are often connected via an ascending stair. Voids and incisions in the resulting form denote space that would be occupied by floors and walls. Windows and doors are seen as surface reliefs and indicate apertures where inside and outside thresholds occur. Notable features of these volumes (unlike the drawings that generated them) illuminate how the architect tailored each space according to the correct height to plan ratio in much the same way a suit is fitted to the body. When viewed from below, we see how stair space is thrust from below into destination spaces, exposing how dramatic vertical thresholds were created and introducing space as a series of dynamic social occurrences as inhabitants moved up and through the building’s section.

In the spirit of Rachel Whiteread’s inversion of form into readable space, the resulting objects from our study reveal themselves as volumetric imprints exposing the limits of raumplan room arrangements. The castings allow us to inspect closely the balance of habitable mass against slim surface features. Along the faces of these models exist the texture of interior walls and ceiling soffits. Windows, doors and other openings understood in relief are oriented outwards, pushing their way through of the void (Fig. 9).

Double Agency

The value of Whiteread’s artistic technique may, in the end, not be directly transferable to architecture or architectural space. Rather, the influence of her method could be thought of as semi-autonomous, a contingent pause that enables a reflexive view of space, and a reminder that architecture as object is often taken for granted. Our discipline’s continued obsession with overt and aggressive form making is not entirely without precedent however. Each generation of new design thinking has turned to architecture’s formal expressiveness. New means of architectural production have driven this trend and our current explorations with complex and exciting formal play are influenced significantly by such innovation. The question of how to remain mindful of space (artistic, cultural, or otherwise) during these changing conditions is critical. A perspective from all sides is required even though it is not always clear.

Could we think of Rachel Whiteread’s process as a sort of double-agency in the architectural design, moving back and forth between allegiances of objects and space, autonomy and contingency, form and culture while also negotiating a bigger picture? Michael Hays’s reminder that architecture must remain critical for this to occur, and that a designer’s responsibility for representing the working knowledge of the discipline runs parallel to its production.7 With this insight we should consider Whiteread’s artistic technique as a potential instrument for this mode of practice.

Adolf Loos, "Architecture" (1910), translated by H. F. Mallgrave, in Midgård, vol. 1, no. 1, 1987, 54.

Rachel Whiteread, "Working Notes", Looking Up: Rachel Whiteread’s Water Tower, edited by Louise Neri (New York: Scalo, 1999), 139.

See details and past works for this temporary London art program at: https://www.london.gov.uk/priorities/arts-culture/fourth-plinth, (accessed October 10, 2015). The inversion of the plinth could also be interpreted as a body casket invoking another alternative reading for the viewer.

Interview by the BBC News, (June 4, 2001), http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/1359423.stm, /accessed October 10, 2015).

Luigi Moretti, "The Structure and Sequence of Space", Spazio, no. 7, 1952-53.

The expression of these utilitarian objects were part of Loos’s manifesto and favorite subjects of his early essays in which the conveniences and modern features of a house should be a part of everyday life. For example, he was particularly appreciative of English and American plumbing.

Michael Hays, Critical Architecture: Between Culture and Form, Perspecta, vol. 21, 1984, 27, doi: 10.2307/1567078.

Figures 1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 9: Photo by the Author (© All Rights Reserved).

Figure 3: Photo by Johannes Ortner.

Figure 4: Photo by Horace Ko.

Figure 5: Photo by Mark Schlemmer.

Peter L. Wong is an architect and Associate Professor at the School of Architecture of the College of Arts + Architecture at University of North Carolina-Charlotte, where he has taught architectural design, history, and theory since 1988. He holds degrees from the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Washington. His design work was recognized with awards from the National Organization of Minority Architects and AIACharlotte. Among his writings is the translation of Vittorio Gregotti’s Inside Architecture> (with F. Zaccheo, MIT Press, 1996). In Fall 2011 he was a visiting scholar and lecturer at the College of Architecture and Urban Planning at Tongji University in Shanghai. An essay featuring his research done while at Tongji was recently published in Diversity and Design: Understanding Hidden Consequences (Routledge, 2015). E-mail: plwong@uncc.edu