Professor in Residence, Department of Architecture, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

Social-impact design challenges many of the assumptions that guide architectural practice such as: What should we design? What program should we design to? What site should we design on? Who should be involved in the design? And what else needs designing beyond what we have been commissioned to do? In raising these questions, social-impact design essentially inverts the expertise model that has guided both architectural education and practice and leads to a more open and responsive mode of practice that looks for the underlying reasons why a problem or need has occurred and the larger systemic issues that surround the project and that may require redesigning themselves. Through a series of social-impact design projects conducted by the Minnesota Design Center at the University of Minnesota, this essay explores what this means in specific ways, through actual projects with diverse communities of people.

The design community has too much of what the writer Teju Cole has called the “white-savior industrial complex.” 1 Too many architects who might want to do social-impact design have a well-intentioned but ultimately misguided desire to help people who appear impoverished, as if we, in the design community, know what is best for marginalized communities. I want to argue instead that the design community has a lot to learn from less-affluent communities, and that by working with them in an open manner, we will encounter important and often quite radical challenges to many of the assumptions that guide current design practice.

In making this argument, I will use examples from the social-impact work that we have done at the Minnesota Design Center (MDC) over the last two years. We have learned how to do this work with the guidance of the communities in which we work, and we have realized in the process how little we know and how much we all have to learn. With that in mind, I present this paper as a progress report more than a finished thesis. In it, I will describe our efforts not as a set of projects, but rather as a set of questions that we have encountered in the process of doing this work, questions that underscore how radical social-impact design can be.

WHAT NEEDS DESIGNING?

A great weakness of current design practice lies in fact that architects often design projects without addressing the larger systems that may, themselves, be dysfunctional and in need of redesign. Too many in the design community see system redesign as not within our purview, which, as I have argued in a recent book, is both a mistaken idea and an enormous missed opportunity. 2 Social-impact design shows how much the redesign of the systems that create the problems we face remains one of the most pressing and important design challenges of our time, to which the design community has much to contribute.

As an example of this, the MDC has worked with four counties and the state government in Minnesota to redesign the adult foster care housing system, based on a 1999 Supreme Court decision (Olmstead v. L.C. and E.W.) that requires that adults with mental and/or physical disabilities have choices in how and where they live. 3 Right now, disabled adults must live in group homes. Architecturally, many of these group homes fit well enough in their contexts and present no major design problem. The real challenge lies with the system itself, which routes disabled adults along one path to a single type of group-home setting.

A designer in the MDC, Emily Stover, has worked with colleagues in our public affairs college as well as with county and state human services staff to lead a series of design workshops, funded by one of the counties as well as a major foundation. These workshops have involved not only the government entities that oversee the current process, but also groups rarely asked to re-imagine an entire system, including the managers of group homes and, most importantly, the people living in the group homes and their families.

The very idea that we would ask service providers and the people seeking services for their ideas and give them a chance to re-imagine the system they work and live with surprised many of them and we met some skepticism at first. But as the process continued in a series of participatory workshops, with diverse groups of people engaged in thinking about better ways to do this, the ideas that emerged were extraordinary, and challenging to many of the assumptions we have about government services and subsidized housing.

A few things became immediately clear. By involving the people most affected by a system, we quickly learned how a system designed to be highly efficient and totally integrated could also become too oppressive and controlled. Residents depicted the adult foster care system as a limited-access highway: once you are on it, there is no way out. Such experiences show the flaw in overly designed systems, with little or no flexibility or choice, created no doubt with the best interests of people in mind, but ultimately oppressing the very ones it seeks to serve.

The process of social-impact design, involving a diversity of people utilizing design methods to elicit their ideas and possible solutions, at the design workshop. Attendees commented that they loved the collaboration and discussion across organizations in an intimate setting and were hopeful that their perspective would be heard in this process to make this system better.

We also learned that ordinary people often have more radical ideas than most professionals give them credit for. The current design practice of an architect working for a client who defines the project can lead to outcomes that may look good and function well, but that end up reinforcing the system as it exists. The ideas that emerged from these workshops showed that people want a far greater diversity of living options – cohousing, cooperative housing, intentional-community housing – than what the current system provides and what many zoning codes and building regulations allow.

Finally, we learned that people see housing in a much broader context than what many in the housing community do. Out of these workshops came ideas that involved retail strategies, neighborhood operations, digital ideas, and service alternatives that might not look like they relate to housing, but that very much affect how people live their lives. We realized through this process that the adult foster care housing system not only needed rethinking; so did the very idea of dividing professional services – be they in the government or in private companies or firms – into categories like housing that many have little to do with the lived experience of people.

WHO DETERMINES THE PROGRAM?

Another weakness of current design practice has to do with the assumption that our work begins when given the program by a client. We would not expect physicians to do what we told them to do, were we to walk into their office with a program of what we want done; we expect the medical professionals to diagnose what truly ails us and to do what needs to be done, whether we like the idea of it or not. The same needs to happen with designers. We should not simply accept the problem as framed by the client. We need, instead, to diagnose the situation that led to the client to seek design services in the first place, to understand not only what is obviously wrong, but also what may be the underlying causes not immediately apparent.

Social-impact design has taught us that there exists a set of questions we need to ask at the beginning of every project: Is this the right program? Who was involved in its creation? And is there a less expensive or more efficient way to achieve the same goals? Investigating the program and having conversations with a diversity of people about it represents one of the most valuable contributions a designer can make to a project, especially one with a public purpose intended to serve community needs.

We have begun such a conversation with the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development as it has begun to rethink how it delivers workforce development education to diverse populations. Like many states, Minnesota has many bricks-and-mortar workforce centers, built in the last century around the model of unemployed people coming to these places to upgrade their skills and look for jobs. That may have worked in the pre-digital age, but with computers widely available in people’s homes or in nearby libraries, and with many internet-connected phones in many people’s pockets, it seems odd to still expect people to go to physical places for information.

The state recently completed a workforce center in north Minneapolis, a community of color, whose program combined workforce training with health and education services. 4 Architecturally, the building has accommodated the program well and has done so in a visually appealing and contextually appropriate way. But the fairly traditional arrangement of offices and meeting spaces reflects an older way of thinking about workforce development.

Conversations that a colleague in the MDC, Dr. Remi Douah, has had with youth in that community shows that many unemployed people want, more than anything, a safe place where they can find social support and not feel isolated or stigmatized being without a job. This in turn suggests that the program of a building like this needs to be less specific in terms of the number and size of rooms for specific purposes, and more adaptable and flexible as a place where people feel they can come to find community, safety and security, with the social service providers as supporters of that community rather than as the primary occupants of the building.

Especially when doing social-impact design, we have learned that programming needs to involve not just the people paying for architectural services, but also the users and community stakeholders, who may have a very different perspective on what they actually need. When given a program, the design professional should not start designing, but instead stop designing and start listening to and learning from the people served by the design and not typically at the table when program decisions get made. If social-impact design will have any impact at all, it needs to be intensely social in every sense of the word.

HOW SHOULD WE DESIGN SYSTEMS?

The same issue arises at the system scale. Like buildings, systems often get designed by the people in charge of them, and as a result, these systems largely work for the convenience of those responsible for their delivery rather than for the people most affected by them. Meanwhile, very few design professionals ever get asked to help with system design, resulting in a lot of poorly designed systems done by well-intentioned experts who often know almost nothing about the design process and how it can arrive at much better solutions when done correctly.

We have seen that in the work that I have done with my colleague, Jess Roberts, the principal design strategist at Allina Health, in the redesign of health systems. Working with leadership at the Centers for Disease Control as well as with various groups of health professionals, we have been impressed by the openness of the medical community to design thinking and to re-imagining the health systems within which they work. Many of these systems have been designed from the point of view of the people delivering services, and so we have tried to move health providers from seeking quick fixes to the symptoms of problems to stepping back and asking more fundamental questions about why these problems arose in the first place and what underlying causes need to be addressed in order to solve them. Challenging assumptions in that way sometimes leads to initial resistance, but design thinking has proven effective in bringing people around to needed and often over-due investigations of what troubles an organization or system.

We have begun to find some commonalities arising from this work. Overly controlled, highly centralized, and top-down systems have begun to give way to more flexible, distributed, digitally based and data driven alternatives that empower people to take more responsibility for their health and that reduce the cost and complications of the healthcare system. Given the health disparities that exist globally – as well as in the U.S. – this constitutes social-impact design at its best: creating systems that promise to benefit most those who have the least access and financial capacity.

Such experiences also show that the scope and reach of social-impact design far outstrips that of the traditional design work that most designers pursue. Social-impact design opens up a vast new territory of activity for those designers who remain open to thinking about their value in terms of their methods and thought processes rather than the objects on which we have conventionally focused our attention. If the design community has a future, it lies with doing much more social-impact design, responding to the needs of everyone on the planet, not just the wealthiest 5 to 10%.

WHERE IS THE SITE?

Social-impact work also challenges the limits within which we design. Here, too, the design community often accepts the project site as a given, without enquiring as to what comprises the real context of the problem. While what the client controls constitutes one set of constraints, human and natural ecosystems have little to do with such boundaries and so, limiting our design work only to what lies under the client’s purview misses the many factors that make the project worth doing to begin with as well as some of the best ideas of what to do on the actual site.

A senior research fellow in the MDC, landscape architect Bruce Jacobson, along with other MDC affiliates, public-health designer Remi Douah and architect Paul Bauknight, have worked with a community in North Minneapolis on the possibilities of a former school playground, now available for the neighborhood to imagine as something more. While the site constitutes half a city block, the real site includes the immediate neighborhood, the nearby commercial corridor, the adjoining transportation links, and the underlying infrastructure and watershed. What people see as the site often extends far beyond the property boundaries and social-impact design can play a vital role in embracing the multiple layers of interests and ideas that exist among those who associate with a piece of land, wherever they may live or work.

The map is a roadway or pathway to the life you want, beginning at the bottom where the person experiences some level of institution. When they get into Corporate Foster Care, they might encounter some barriers. The bottom right corner symbolizes government as the organization responsible for funding and rules - there’s more money at the start of the journey, and lesser or none at the end. As we move up, the person is more independent. The end goal is less defined but would elicit joy.

Social-impact work can also reveal missing layers of civic society. My MDC colleagues John Carmody, Bruce Jacobson, and Bob Close have developed design guidelines for two urban areas: one an innovation district spanning the cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul and the other in the city of Rochester, Minnesota, home of the Mayo Clinic. In the latter, a partly state-supported Destination Medical Center initiative has created a very effective public/private partnership that has enabled that city to think about its urban core as a set of sub-districts with a cohesive public realm and shared infrastructure. Having an intermediary like the public Destination Medical Center board and its private partner, an Economic Development Agency board, able to convene and connect public and private interests has made all the difference in creating accessible places and equitable environments. The social impact of their vision to create “America’s City for Health” makes it one of the most interesting efforts underway in a country whose public health remains at the bottom of the developed nations of the world.

The innovation district in the Twin Cities has had to bootstrap its efforts, with an actively engaged board that includes property owners, developers, city representatives, and neighborhood members, but with relatively little funding to create the needed district infrastructure and public space. While the district is only now getting built, some of its initial moves, like the commissioning of an innovative green-street design have shown how a committed group of people with no regulatory authority can still spur an amazing level of cooperation among landowners. As in all social-impact design, human capital can often compensate for a lack of financial capital and the power of collective action can often trump individual self-interest.

Social-impact design adds value, as well, by showing how to utilize sites that others don’t see. Mic Johnson, an architect who served as the interim director of the MDC, led a team that included Jacobson, Close, and Carmody, to envision sites for buildings and open spaces next to and on top of existing, below-grade highways. While at first received with some skepticism, the idea of constructing buildings on the grassy land next to highways and within cloverleaf interchanges, with public open space bridging over the highways eventually attracted adherents. A big part of the appeal lay in the possibility of reconnecting impoverished neighborhoods divided by highways in the 1950s and 1960s and creating residential, recreational, and economic development opportunities that these communities do not now have. The ability of designers, in a case like this, to see opportunities that others have missed and to have a significant social impact on several fronts with a single strategy indicates the value of this work and why its funding often generates many times its value in public and private benefits.

WHAT IS THE PUBLIC REALM?

The architectural community mostly works within the dichotomy that defines the legal definition of property ownership and legal responsibility, designing projects either on public or private land, for public or private and non-profit clients. This runs counter to the insights of writers like Henri Lefebvre that space is socially constructed and defined by our experience of it as a series of gradations of semi-public and semi-private spaces that we continually cross and most of the time successfully negotiate every day. 5 Social-impact design suggests that while architects’ clients might be public or private, the people we design for have a much more nuanced understanding of the spaces they traverse.

The map is about the person, and his road to the desirable areas, services, communities, choice, and money. On each side are the challenges the person is facing (e.g. managing background issues, get desired employment, support for training, etc.). Person-centeredness is helpful to get him to where he wants to achieve his needs.

This becomes especially pertinent in the design of the public realm. In a study that MDC staff members Bruce Jacobson and Joseph Hang have led for the Ramsey County Regional Rail Authority’s Riverview and Rush Line transit corridors, the fluid nature of the public realm has become very apparent. The Riverview Corridor, for example, connects downtown St. Paul to the airport and Mall of America and it requires threading several modes of transportation – cars, buses, bicycles, pedestrians, and possibly light-rail or street-cars – through a relatively narrow public right-of-way. At the same time, the emergence of car sharing services and autonomous vehicles may change the space requirements of different modes of transportation.

In such dynamic situations, social-impact design brings a lot of benefit. The design team has created a series of physical and digital models that allow the diverse stakeholders in this project to change out various alternatives and look at their impact in real time. The flexibility of the models also prepares the community to think about the public realm in more flexible or switchable ways, since accommodating today’s technology of vehicles driven by people and of trains on fixed rail may change dramatically in another decade or two, well within the useful life of the infrastructure that will be put in place. While the engagement of diverse points of view may lead to multiple perspectives that can seem contradictory, such social-impact design helps us all acclimate to a future that, regardless of the black-or-white way in which we divide the city into public or private property, will be increasingly characterized by ambiguity, contingency, and adaptability – a world that consists mainly of shades of grey.

That has led to very different kinds of streets than what have existed in the past. In the Minneapolis and St. Paul innovation district, a new street, “Green 4th,” embodies the various goals of the guidelines that the MDC developed under the leadership of John Carmody. Designed by Snow Kreilich Architects and the landscape architects Oslund Associates, Green 4th provides access for cars, but it does what few vehicular streets have done in a long time: it privileges the pedestrian. The street has Snow-Kreilich- designed picnic tables, seat swings, steps, and platforms aimed at encouraging people to work, socialize, play, and perform – all within the public right-of-way. 6 This envisions a public realm no longer just devoted to moving vehicles, but instead as a series of places that people care about and want to be in: design for social impact at its best.

WHAT IS A COMMUNITY?

Social-impact design can help us think about the world not from the vantage point of those supposedly in control, but from that of those most affected by these systems. In the adult foster care project, for example, several ideas emerged that have an ecosystem-like character. One group re-envisioned the delivery of government service by having a “neighborhood navigator” who would be in the neighborhood, knowing who needed what services and helping people access them. Rather than expect people to go to government offices, this idea would bring government services to where people live and work and would likely increase the satisfaction of employees who would have more direct contact with people as well reduce the cost of government by focusing more on prevention than on crisis response. Such a paradigm shift shows social-impact design creatively rethinking a system to get more with less.

Another idea to come out of this project was the creation of intentional communities in which people in the adult foster-care system had the opportunity to choose who they live with, something that they don’t have available to them now. This suggests that the way in which we think of housing as a set of units available to buy or rent misses the point about how people seem to want to live, in communities of people with similar interests and values. Creating processes that make it easier for all people to find and live in such communities is another role for social-impact design.

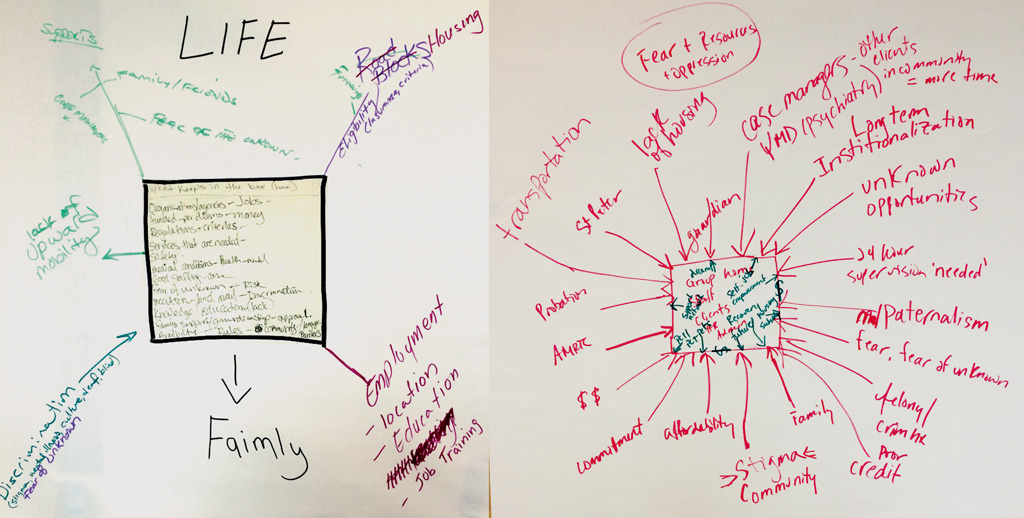

This divergent thinking exercise encouraged providers to consider what were the elements of the care system and what defined the ‘box’ in this system. Left. Within the box there is the fear of the unknown. Outside of the box: housing, funding, roadblocks, employment, job training, mobility. Fear of the unknown works from the inside and outside. Right. Within the box are the pressures that make the box stay closed – fear, resources, stigma, families, financial pressures, affordability, various institutions, lack of housing, guardians, your care team. How to break from the box: self-empowerment, recovery, money, housing subsidy, person-centered planning and thinking.

At the same time, we heard from participants in this project a desire to have places in which people of all abilities can hang out together. The need for such “third places” that enable people to gather and linger has come up repeatedly in the social-impact work we have done, suggesting that the public sector should focus on incentives to encourage private property owners to create and maintain such places. The relative lack of third places in our cities, especially for those with few means, shows how social impacts can happen in modest ways, with relatively few investments and often in spaces that already exist.

We also heard that people want more flexibility and a greater sense of community in how they live. Current housing practices rest on a very white, middle-class set of assumptions about how people should live, often with an emphasis on privacy and on a minimum of shared space. As we have listened to the needs of families in need of extremely affordable housing, they often want something very different: less private space and more shared space with the ability to share cooking, childcare, maintenance, and possessions that they need only on occasion. That such co-housing and cooperative housing faces regulatory obstacles and zoning barriers shows how much our public policies often reinforce the assumptions of those who make the laws rather than the needs of those who suffer under them.

WHAT HAVE WE LEARNED?

Professions put great store into expertise, licensing members according to their command of technical information and disciplinary knowledge. While that has considerable value, evident in the remarkable advances we have made in so many areas of human endeavor, including the health and safety of the built environment in countries like the U.S., that focus on expertise has led to what the sociologist Harry Braverman called the “deskilling” of ordinary people. 7 This seems particularly ironic in architecture, since communities of people have built shelter for themselves for thousands of years before architects ever existed.

Social-impact design offers a critique of that whole system. While some tradition-minded architects may think that everyone in the field cares about the social impact of our work and so downplay the radical aspect of social-impact design, we find that doing this work continually challenges common assumptions about the process of design and profession of architecture. Most architects care about society and the effect their work has on the lives of people, but with the expertise model of professionalism, that has largely remained a top-down imposition of the client’s and architect’s beliefs on people who may want, need, and value something very different. As mentioned at the beginning, however well intentioned the architectural community may be, we have perpetuated the white-savior industrial complex as much as any other profession.

Social-impact design comes at people’s needs from the opposite direction: empathetically listening to the very people rarely heard, facilitating people’s active engagement in reframing problems and imagining possible solutions, remaining open to what emerges from this process and questioning any assumptions counter to that, and helping people achieve their vision, using expertise as a supportive tool rather than an oppressive one. Social-impact design may not fit the personality or the perspective of every architect, nor does it need to. But it seems clear to us, having done so much of this work at the MDC, that if we want the architectural profession to thrive in the future, social-impact design has to play a central role. The profession can either continue to serve the world’s wealthiest and shrink in size and importance accordingly, or it can begin to serve the billions of people who need our services even more than the rich – and grow our relevance and impact as a result.

Teju Cole. “The White-Savior Industrial Complex,” The Atlantic. Washington DC: The Atlantic Media Company, March 21, 2012

Thomas Fisher, Designing our Way to a Better World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016, Chapter 1.

A good overview of the topic can be found at this U.S. Department of Justice website: https://www.ada.gov/olmstead/olmstead_about.htm.

Eric Roper, “Long-awaited WorkForce Center in North Minneapolis Aims to Ease Disparities,” Minneapolis Star-Tribune, December 1, 2015. http://www.startribune.com/protests-loom-over-north-sidegroundbreaking/3....

Henri Lefebvre, Donald Nicholson (translator). The Production of Space. New York: Wiley-Blackwell, 1992.

Thomas Fisher. “At the Corner of 4th and Innovation,” Star Tribune. December 19, 2015, http://www.startribune.com/streetscapes-at-the-corner-of-4th-andinnovati....

Harry Braverman. Labor and Monopoly Capitalism, The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1998.

The images were provided through the courtesy of the Metropolitan Design Center, College of Design, University of Minnesota.

Thomas Fisher is a Professor in the School of Architecture and Director of the Minnesota Design Center at the College of Design, University of Minnesota. He also holds the Dayton Hudson Chair in Urban Design. One of the most frequently published authors about architecture in the U.S., according to the Key Centre for Architectural Sociology, he has published nine books, 59 book chapters or introductions, and over 420 major articles in journals, magazines, and newspapers. E-mail: tfisher@umn.edu