Professor in Residence, Department of Architecture, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

Once a clinical cure for COVID-19 is found, which infection prevention practices – both social and spatial – might remain, and what long-term impacts will they leave? This article examines the interrelationships between airborne diseases, social practices, and the design of physical and digital infrastructures for cities. Historically, infectious diseases have left long-term imprints on cities, from plumbing to hospitals. Spatial practices to prevent infection, such as clear physical barriers and car-free streets for socializing, must be implemented with a close examination of impacts on the mental, social wellbeing of both individuals and the broader community. Prevention practices examined include the use of transparent barriers that separate and connect people, the increased use of open windows, the adaptation of sidewalks and roads for physically distant socializing, and spatial negotiation and trust-building that occur in public spaces. As cities make design and policy changes to protect their citizens from the invisible virus, they must be mindful of the imprints the physical, social, and policy changes have on comprehensive wellness and equity for all people.

The world now anxiously awaits the development of a COVID-19 vaccine so that we may gather and travel more freely again. But once a clinical cure is found, which infection prevention practices – both social and spatial – might remain, and what long-term impacts will they leave? How might the impacts be different from those left by diseases of the past centuries? The practices of social distancing, wearing masks, and transparent barriers may or may not continue when a vaccine is found, but sociologist Richard Sennett speculates that these practices governing public spaces in cities will outlast the pandemic due to a learned fear of the invisible.1 He bases this on examples of security measures practiced immediately after 9/11, such as ID checking and x-ray scanning at building entries or airports, that remain the norm decades after the terror attack. He suggests that people will continue to fear proximity to others, and social distancing will become the standard.

Some new or renewed practices, such as increased natural ventilation with operable windows or closing off vehicular roads to make way for safe outdoor gathering, are opportunities to see our built environment in a new light and to consider possibilities that may have seemed improbable before the pandemic. Architectural interventions made as disease prevention measures must be examined for non-clinical consequences; if offices, banks, and cafes install acrylic or glass partitions, the social and psychological implications of these transparent barriers demand studies. The pandemic has also illuminated the increasing correlations between digital and physical infrastructures. As people shop online from home, the upsurge in e-commerce has had a profound effect on delivery workers and the infrastructures of roads and warehouses that enable the transport of goods. As we move forward through the pandemic, what are the questions we should be asking regarding the interrelationships between airborne diseases, social practices, and the design of physical and digital infrastructures for cities? Moreover, how could we strive to make cities more equitable than before the pandemic?

HISTORIC IMPACT OF PANDEMICS ON CITIES

Historical examination of how diseases have changed cities sheds light on how COVID-19 may leave similar or entirely different impacts. The idea of social distancing to prevent infection is not new. The word “quarantine,” rooted in the Latin word meaning “forty days,” was a measure taken in Venice during the fourteenth century to prevent the spread of the plague.2 Ships arriving in Venice were required to stay anchored for forty days before landing. Since COVID-19 is a novel virus with no vaccine or clinical treatment, the world has come to depend on trusted, medieval practices of quarantine and social distancing.

Hospitals, Sanitoria, and Their Healing Effects

Historically, infectious diseases – spread either directly through touch or indirectly through air or water – have left long-term imprints on physical designs of infrastructure and buildings. The type of architectural response is associated with the duration of recovery from an illness. For diseases with long recovery periods, architects design buildings with healing effects for specific symptoms. Small pox, polio, and tuberculosis have recovery periods that last up to several months. Patients of these diseases were quarantined for months to prevent infecting others and isolated long-term in buildings located away from cities on islands, such as the Roosevelt and Brother Islands on the East River in New York City, or in the mountains or forests, as with the Sanatorium Zonnestraal (Fig. 1) by Jan Duiker in Hilversum, the Netherlands and Paimio Sanatorium by Alvar Aalto in Finland. Built during a time when architecture reflected the beliefs in the healing effects for respiratory diseases, the sanatoria featured long balconies for exposing patients to sunlight and fresh air, large operable windows which were left open to increase air circulation, and white walls that epitomized hygiene.3 Besides healthcare and living spaces, Zonnestraal offered occupational training facilities where patients could learn new skills for jobs after recovery. In other words, this exemplary sanatorium treated the whole person, including their medical and occupational wellbeing, a feature that is still uncommon in healthcare facilities.

When vaccines and other clinical cures for a disease are found, some means to suppress infections remain permanently, whereas others become eliminated in obsolescence. Tuberculosis sanatoria of the early-twentieth century were either abandoned or converted to general hospitals around the 1950s when triple-drug therapy became readily available. While the physical sanatorium may no longer exist, the aesthetics of white, modern hygienic machines, which Le Corbusier advocated extensively in his written and built work, remain common in hospitals to this day. However, the reliance on clinical cures eventually led to the disregard of the hospitals’ physical environment as a means to wellness. As Michel Foucault observes in his book The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception (1963), hospitals at the time were designed for efficiency and control, with patients treated not as individual humans but as diseases to be medically cured.4 Patient rooms often had no daylight, views, or natural ventilation. In the late 1900s, when hospitals moved to the suburbs from dense, city centers, patient rooms once again had access to daylight and views. Today, hospitals are designed to meet the increasing demands of baby boomers, who expect a curative environment beyond clinical care, including gardens, fountains, artwork, and the comforts of a domestic or hospitality setting.5

Diseases and Physical Infrastructures

The effects of diseases are found not only in individual buildings but also in large-scale infrastructures. During the mid-1800s water-borne cholera outbreaks in London, physician John Snow traced an outbreak to a contaminated public well on Broad Street. Snow’s discovery that linked the disease to polluted water soon shaped urban architecture and engineering, including the construction of over eighty-two miles of sewers along the River Thames. What had been the city’s open sewer was now underground, with public parks and roads built over the tunnels.6 The 1832 cholera outbreak in New York City, which impacted the crowded tenement buildings of lower Manhattan the hardest, resulted in policy changes to better protect citizens from the deplorable living conditions, particularly for the poor who were disproportionately affected. New York City’s Housing Act of 1867 required residential buildings to have air shafts, private bathrooms, and access to windows for light and air in bedrooms. The response to cholera also introduced infrastructural changes and building codes, including the requirements of water towers to maintain plumbing pressures and, for every twenty tenants, one toilet connected to a sewer line.7 In these ways, diseases leave marks with changes in buildings as well as policies and laws that remain long after clinical cures have been found.

Central Park and Public Health

An exemplar of an interdisciplinary collaboration between public health and design, the Central Park in New York City was designed, beginning in 1857, by landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, with architect Calvert Vaux. In the commissioned design proposal, Olmsted and Vaux argued that this great public park would function as the “lungs of the city,” an open space that provided the city with plentiful, clean air.8 Earlier in the century, scientists had linked diseases such as cholera and tuberculosis to damp, crowded, unsanitary living conditions. Socially conscious and progressive, Olmsted designed the parks to embody his egalitarian ideals of public spaces that are freely accessible to all citizens.

Although more often recognized for his work in landscape architecture and as the profession’s founder, Olmsted also served as the general secretary of the US Sanitary Commission (a precursor of the Red Cross) during the Civil War for two years from 1861. While in this role, as Thomas Fisher writes in his article “Frederick Law Olmsted and the Campaign for Public Health,” Olmsted witnessed firsthand how the soldiers’ physical environment affected their mental as well as physical wellbeing. Seeing how exhaustion, heat, and lack of food and water demoralized the troops, Olmsted advocated for improved sanitary conditions in drainage, waste disposal, ventilation of tents, and food preparation and storage. His acknowledgement of this link between the physical environment and health indisputably shaped the design of his future parks, including the Prospect Park in Brooklyn, the Riverside Park in Chicago, and the park system in Buffalo, New York. In April 2020, when New York City was the COVID-19 epicenter, a sixty-eight-bed emergency field hospital appeared in Central Park. The tents treated patients from Mount Sinai Health System and were operated by the evangelical Christian relief group Samaritan’s Purse, whose staff had been deployed in the Demographic Republic of Congo to treat Ebola patients, as well as in wartime Iraq and after a hurricane in the Bahamas.9 Lined with white triage tents, the scene appeared to be a flashback and a homage to Olmsted and his days of working in Civil War battlefields. In addition to housing an emergency hospital, for socially distanced New Yorkers, public parks in the city have become a place of healing and refuge, and an escape from the pandemic’s woes.

Mass Destruction of Neighborhoods

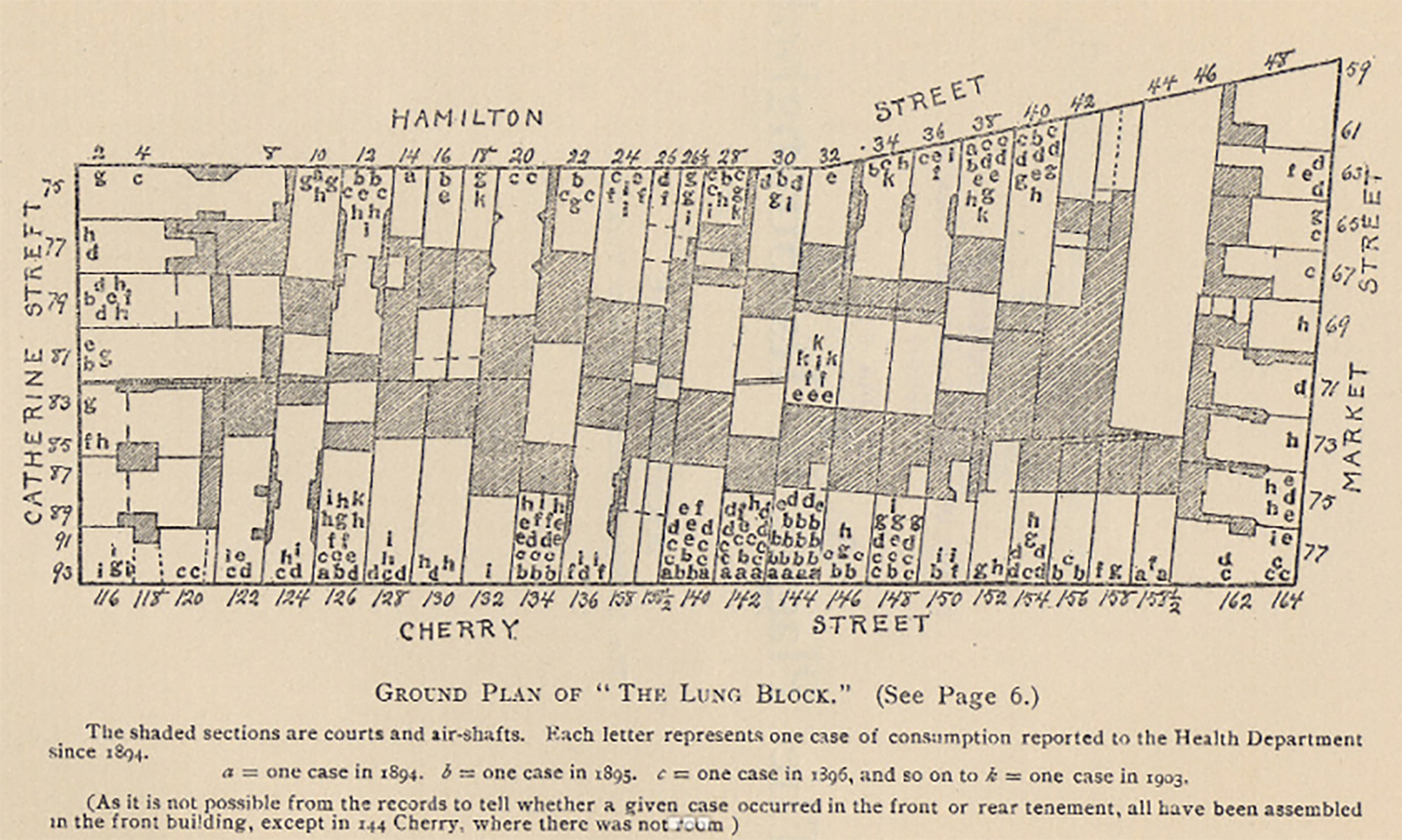

Other historic infrastructural changes remind us of mistakes not to repeat. A prime example is the razing of “lung blocks,” minority neighborhoods in the US inflicted with high tuberculosis rates during the mid-1900’s urban renewal (Fig. 2). This effort to sanitize neighborhoods that suffered from high infection rates displaced tight-knit communities and contributed to the residents’ psychological despair, drug addictions, poverty, and other social diseases. In his book Infectious Fear: Politics, Diseases, and the Health Effects of Segregation (2009), Samuel Kelton Roberts writes on the social and political legacy of tuberculosis. Following the discovery of clinical cures for the disease from the late 1940s to the early 1960s, traditionally African American neighborhoods were demolished en masse, displacing families and small business and lacerating communities that had taken decades to build. These areas were deemed too crowded, damp, unsanitary, and conducive to lung afflictions according to the federal housing guidelines.10 Roberts argues that, in minority neighborhoods, the medical intervention of tuberculosis did not end the suffering from the disease as many historians claim. Instead, in what Roberts calls “the triumph of infectious fear,” 11 the mass destruction of Black housing in the name of progress led to decades of further segregation and a widened equity gap. The clinical illness was nearly eradicated, but the neighborhoods were left in worse conditions due to the social destructions resulting from the mass demolition of communities.

SOCIAL IMPLICATIONS OF PREVENTIVE MEASURES

In medicine, search for a biological cure for a disease has been primary, but doctors who practice social medicine are equally concerned with the social phenomena of diseases. Paul Farmer, a physician and anthropologist, co-wrote in a 2006 article “Structural Violence and Clinical Medicine,”

The holy grail of modern medicine remains the search for a molecular basis of disease. While the practical yield of such circumscribed inquiry has been enormous, exclusive focus on molecular-level phenomena has contributed to the increasing “desocialization” of scientific inquiry: a tendency to ask only biological questions about what are in fact biosocial phenomena.12

Farmer and his colleagues assert that clinicians and public health officials need to ask themselves questions at the beginning of a disease treatment rather than at the end, such as “Does our clinical practice acknowledge what we already know – namely, that social and environmental forces will limit the effectiveness of our treatments?” Farmer also asks whether we can even speak of these diseases without addressing the social forces, including racisms, pollution, poor housing, and poverty that shape the course of diseases in both individuals and populations. To treat HIV/AIDS in rural Haiti and combat structural violence – or an impairment of basic human needs due to social structures, including economic, political, legal, religious, and cultural – Farmer and his team found an effective treatment with the non-profit organization Partners with Health (PIH). PIH’s approach combines a treatment at a conventional clinic with home-based supportive care by a local person – usually, a neighbor – who is trained to deliver drugs and other care. This coupling of clinical and community-based care has proven to be the “world’s most effective way to remove structural barriers to quality care for AIDS and other chronic diseases.” 13

Likewise, interventions made in architecture and urban design, when implemented without acknowledgement and consideration for the social forces that impact the effectiveness, can ultimately do more harm than good. During the razing of the lung blocks in the middle of the century, the US government’s Public Housing Administration and the Urban Renewal Administration demolished 2,500 neighborhoods in 993 cities, which were largely populated by African Americans.14 Baltimore, where its “lung blocks” with dilapidated wooden houses had the highest crime rates, was more segregated than its peers in 1940; it remains one of the most racially disparate cities in the US today.15 The recent killing of George Floyd in Minnesota brought to light persistent racial segregation in Minneapolis-St. Paul, a metropolitan area often touted as one of the most progressive, livable cities in the US. The Twin Cities’s current reputation as the sixth “Best Place to Live in the US,” 16 as with many assessments on the quality of life, is from the perspective of those in power and holds true primarily for the white majority. Floyd’s death and the consequent uprising brought a profound awareness of this contradiction in Minnesota. Racial segregation in the Twin Cities can be traced back to – along with redlining and other denials of services through policies – the destruction of thriving minority neighborhoods such as the Rondo in St. Paul in the 1950s and 1960s in order to make way for an interstate. One in every eight African Americans in the city lost their home, and many businesses permanently closed.17 There are lessons to learn from these stories and the field of social medicine. Paul Farmer qualifies the medical model based exclusively on a molecular basis and upholds one that examines medicine as a social as well as a biological practice. Likewise, the design of buildings and cities needs to be examined for long-term social implications of physical disease prevention and public health measures.

NEW SPATIAL PRACTICES IN THE AGE OF COVID-19

Over the last six months since the outbreak, the United States has seen several conspicuous changes in spatial practice: transparent physical barriers between people to intercept droplets and aerosols; increased natural ventilation indoors; the shutting down of vehicular roads to expand outdoor spaces for dining and socializing; and the emergence of “delivery lanes” in urban areas for online shoppers’ shipping boxes and food delivery bikes and cars.

Transparent Barriers

On February 27, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) published a recommendation to install transparent barriers of glass or acrylic to conserve the need for Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). The guidance recommends:

Use physical barriers to reduce exposure to the COVID-19 virus, such as glass or plastic windows. This approach can be implemented in areas of the healthcare setting where patients will first present, such as triage areas, the registration desk at the emergency department or at the pharmacy window where medication is collected.18

The barriers perform three functions: to intercept the droplets that carry the virus, to remind people of physical distancing requirements, and to reduce reliance on masks when there is a shortage of PPE.19 By mid-March, as US schools and offices abruptly locked down, physical barriers quickly appeared to “flatten the curve” of infection rates. The barriers were not limited to medical spaces. In order to protect the health of its employees and customers, clear acrylic barriers were erected at cashier’s counters, taxis, buses, post offices, and banks. Office furniture companies quickly speculated a rise in sales of partitions in the coming months. Partitions have been built as an emergency public health measure with little design considerations; however, long-term social implications of these public health measures cannot be ignored.

Transparent materials such as glass or acrylic allow people to see each other’s faces, which is generally preferred over opaque materials that prevent seeing facial expressions and body language that convey emotions. Seeing gestures and mouth movements is also more equitable for people with hearing difficulties. Although transparent facial masks have been designed in response to such concern, even a clear material is a barrier. Sounds are muffled, tactility is lost, and reflections on the surfaces can obstruct vision (Figs. 3, 4). Acrylic barriers can remind us of high security, stressful interactions, such as sitting in the back seat of police cars or visiting incarcerated family member at a prison. An interior full of transparent barriers may resemble scenes from Jacques Tati’s film PlayTime (1967), in which the main character Monsieur Hulot becomes befuddled and lost in the world of modern office cubicles and endless reflections. Barriers can create a sense of separation, obstacle, and hierarchy. Over the past couple of decades, offices have removed partitions between employees in order to create less hierarchical, more open, egalitarian office environments. Now, these partitions may need to be revived, this time to protect people’s health. In doing so, companies must be mindful of how these barriers may create unintended hierarchies and obstructions for communication.

Fear of Air Conditioning

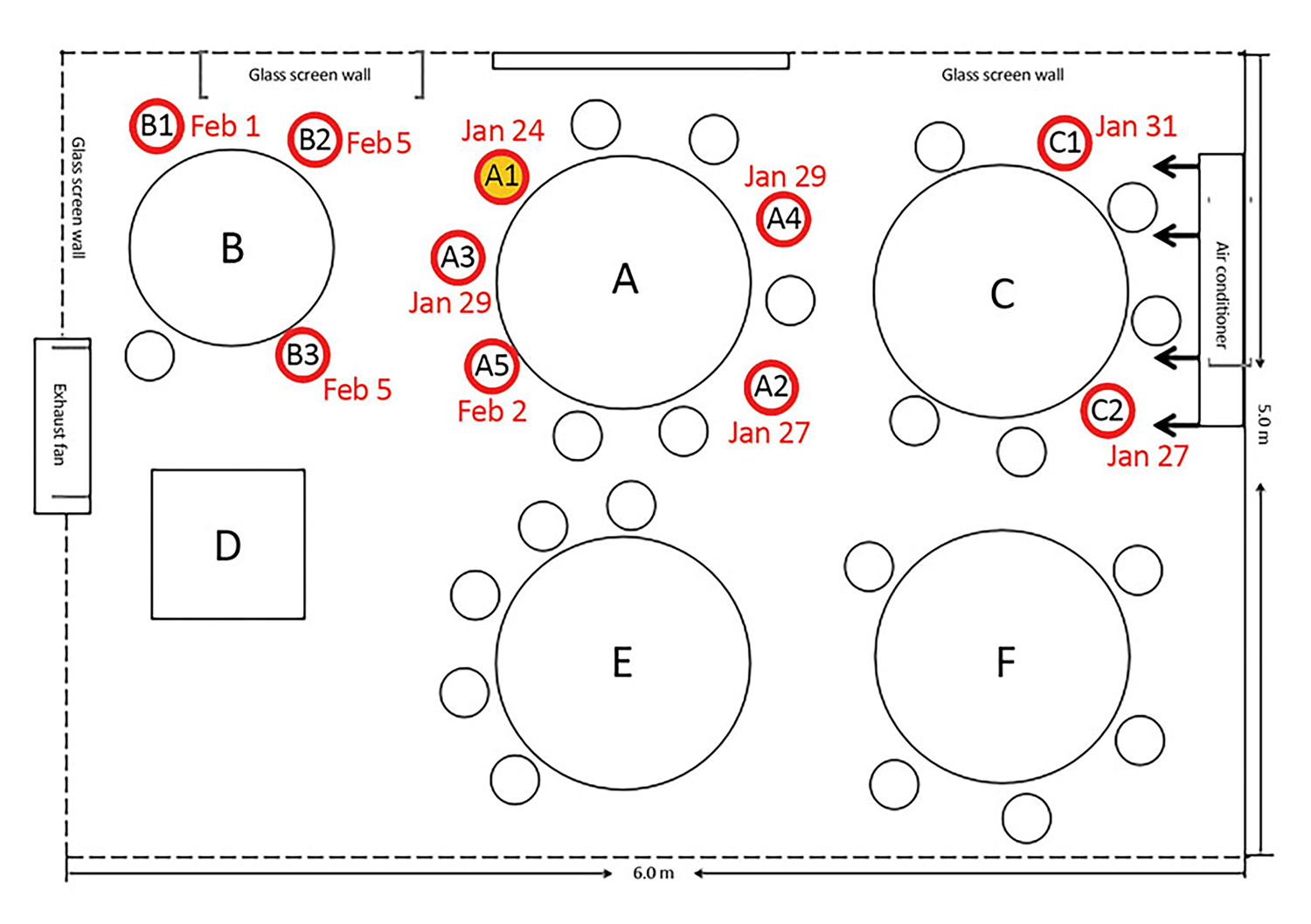

Studies have shown that people are more likely to be infected indoors where the air is recirculated with limited intake than when they are outdoors. Indoors, air droplets from an infected person remain in the air and can become inhaled by others. Whereas outdoors, droplets disperse quickly with constantly moving air.20 Edward Nardell, a professor of medicine and of global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School, says this is a reason why hotter southern cities, where people are in air-conditioned spaces, saw an increase in infection rates in June 2020.21 HVAC systems with an appropriate filter system and fresh air intake can help to remove virus from the air and mitigate infections, but when the air is recirculated, an air-conditioned building or aircraft can increase the rate of virus transmission. In a study of a windowless restaurant in Guangzhou, China, ten people from three families who dined at adjacent three tables, sharing the same air conditioning intake and outtake, became ill with COVID-19 within twelve days of each other (Fig. 5).22 The study showed consistency between the airflow direction with droplet transmission. Stories like this have instilled fear in people that, inside a building, a modern technology that provides thermal comfort may be a medium for a fatal virus, and a person well beyond six feet away could be infecting them through air ducts. The fear of physical environment is intensified by the deadly virus that is not only is invisible but travels through air which had previously been assumed safe, thus intensifying the fear of infection.

As schools, offices, and stores keep their windows open to improve fresh air circulation, the occupants may be better protected from the deadly virus, but what impacts could the open apertures have on indoor humidity, allergens, and crime? Moreover, many modern glass curtainwall skyscrapers and office building do not have operable windows. The movement towards open windows demands the design of HVAC systems that better filter indoor air, as well as crime monitoring systems to deter burglary and assaults.

A New Life on the Sidewalk

Fearing infection from recirculated or stagnant air, people have come to view the outdoors as a sanctuary. Camping and hiking have surged since the pandemic, and restaurants have limited or closed indoor seating and expanded outdoor dining (Fig. 6).

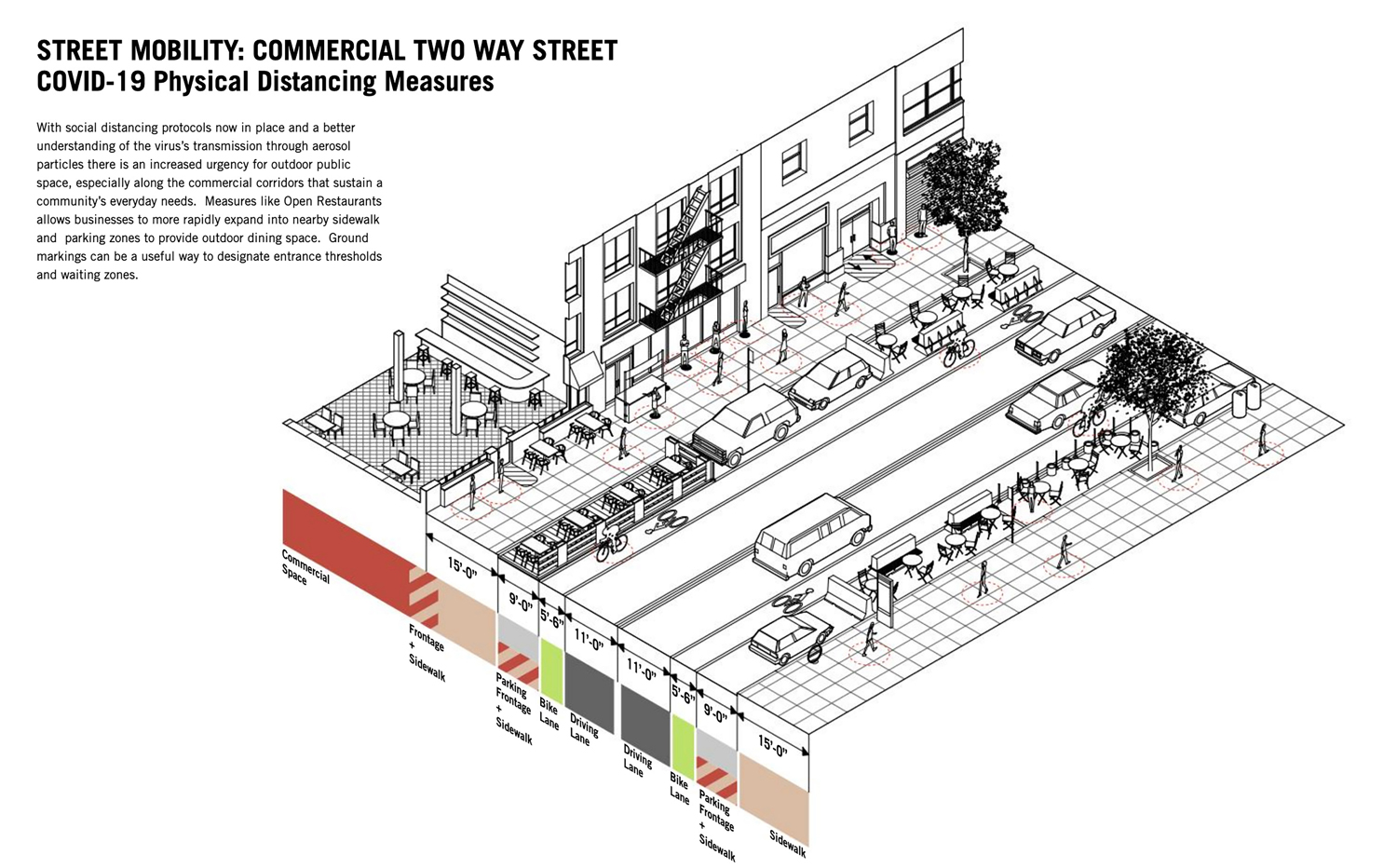

From New York City to small college towns, municipalities have closed streets to cars to make way for restaurant seating, planters, and publicly accessible picnic tables. In the 2020 document Manual of Physical Distancing, LTL Architects, along with engineering firm Guy Nordenson and Associates, have extensively documented case studies of social distancing on New York City avenues and cross streets (Fig. 7).23 Their drawings suggest how the roads might prioritize pedestrians and cyclists while vehicular traffic and subway ridership are low, and ask how street furniture may be adapted to accommodate multiple modes of proximity. Active and reimagined uses of pedestrian roads, sidewalks, and parks may become a lasting legacy of the pandemic.

On the other hand, a proposal such as the one by Practice for Architecture and Urbanism (PAU) with Buro Happold to ban all private vehicles in Manhattan requires a critical examination. Despite the benefits of greenery, ridesharing, and micro-mobility, the banning of cars, as Aaron Betsky warns, may exclusively benefit Manhattanites who are already privileged, with short or no commutes and access to extensive public transportation which the majority of the US population lacks.24 These plans would, while making Manhattan greener and cleaner, not serve those who in the other boroughs who have already been priced out of Manhattan. For the vast majority of this country for whom cars are an everyday necessity, they too need a visionary plan that enables more active sidewalks, walkable commercial districts, cleaner air, and access to parks.

Cities in Italy have seen medieval architectural elements return to life during the pandemic. Customers in Florence can now buy glasses of wine, coffee, and sandwiches from the sidewalk through one of nearly 150 medieval wine windows in the city (Fig. 8).25

Used during the medieval plague, the stone-framed openings in building façade of large houses are just large enough for a mysterious hand holding a wine bottle or glass to pass through, without the server and the customer seeing each other’s faces. This peculiar anonymity to avoid face-to-face encounter has also become a familiar phenomenon in other transactions, such as leaving one’s pet in a cage in the vestibule or in front of a veterinary clinic, from which a clinician picks up the pet as the owner watches cautiously from the sidewalk. While these practices are different from the sidewalk and stoop interactions that Jane Jacobs describes in her 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities,26 they are informal interactions that build a form of public trust between strangers during a pandemic. Jacobs writes, “the trust of a city street is formed over time from many, many little public sidewalk contacts,” 27 and that the “brains behind the eyes on the street” are essential for safe neighborhoods. These interactions that build and depend upon trust, despite the physical distance, continue to occur. For instance, people are more mindful of where they stand relative to others in grocery stores or outdoor markets, out of respect for both others’ safety and their own. Although interactions are restricted while keeping a physical distance and partially covering our faces, today there is a great deal of unspoken – and occasionally spoken – negotiations that occur when people share the sidewalk or a grocery aisle. Recurrent reminder e-mails and posted signs are necessary now as people acclimate to new ways to navigate shared spaces. Such navigation under new protocols requires a collective purpose to build public trust and to protect each other in a community, precisely as Jacobs advocated in the 1960s. From cities to rural small towns, the pandemic has brought more private life out on to the public streets and parks (Fig. 7). The pandemic has brought to light the importance of communities coming together to protect one another in mutual respect.

Physical and Digital Infrastructures Intertwined

The pandemic has brought to light how the physical infrastructures of cities are shifting as a result of a surge in e-commerce, an already occurring phenomena that became amplified by COVID-19. As a Bloomberg CityLab article suggests, “digital infrastructure might be the sanitation of our time.” 28 If diseases of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries transformed plumbing infrastructure in cities, then diseases of the twenty-first century may alter how physical and digital infrastructures intertwine.

In August 2020, the American Institute of America (AIA) New York hosted a virtual forum called The Transformed City: Infrastructure Now, in which four panelists discussed “how COVID-19 has stressed digital and physical networks in transportation and infrastructure.” 29 David Vega-Barachowitz, an associate of WXY Architecture + Urban Design, discussed how, in front of WXY’s office in downtown Manhattan, an “impromptu micro-distribution hub” appeared as trucks of FedEx and other delivery companies have taken a lane on the street to unload and spread dozens of boxes to prepare for delivery to the surrounding blocks. Panelists also discussed the emergence of e-commerce warehouses that have appeared in towns along interstates leading to New York City and other transportation hubs. Virginia Tech has introduced PickUPP Lockers at four outdoor locations across campus where students can choose to pick up packages shipped to them, in an attempt to reduce person-to-person contact and waiting in lines (Fig. 9). The surge of online shopping during the pandemic has intensified prevailing issues in delivery infrastructures, from the demand for a new type of lane in a road to a building type: prefabricated locker sheds on a college campus.

The use of food and grocery delivery apps has become a standard practice during the pandemic for those who had not adopted them earlier. Subsequently, the increase in deliveries impacts the physical infrastructure of parking. Vans and cars need a place to park briefly while the carriers take the boxes of goods to the doorman or the individual unit. Whereas parking in a driveway of a suburban home is easily accommodated, finding short-term parking spots in large cities presents challenges. At suburban grocery store parking lots, rows of parking spots have become curbside pickup locations where drivers waited while checking their phones or reading book. While the parked shoppers’ cars decreased in number, the online order pickup rows became fuller, shifting the landscape of parking.

In addition to physical environments, an increase in deliveries also affects the working conditions of delivery workers. Maria Figueroa of the Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations questioned the risk of crime and traffic accidents, lack of employment benefits, and virus exposure encountered by delivery workers, who are predominantly minority immigrants whose vulnerabilities have been exacerbated during the pandemic. The pandemic has highlighted the disproportionate percentage of delivery workers, along with warehouse workers, janitors, truck drivers, and other low-paid first responders who have been exposed to the virus while many privileged workers are able to work from the safety of their homes. In most cities, 60% of warehouse and delivery workers are people of color, and in Newark, the rate is 95%.30 Cities need to question how to protect their first responders in order to accommodate these shifting needs, which will persist as delivery culture remains a common practice after the pandemic.

Fear of Dense Cities

In her May 15, 2020 article in the New York Times, Mary T. Bassett, the director of the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard University, argues that density in cities, despite the general assumption, is not what causes high rates of infection.31 In fact, in New York City, the death rates were higher in boroughs such as the Bronx and Brooklyn, which have a lower density than Manhattan. By comparison, these boroughs have overcrowded households, where large multi-generation families live in tight quarters because larger units are unaffordable. These boroughs also have a higher number of Black and Latino residents, who suffer from inadequate access to healthcare, public transportation, parks, and other services, which are long-term impacts of historic redlining. A 2020 research on density and the COVID-19 pandemic by Shima Hamidi et al., funded by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, shows that “density is unrelated to confirmed virus infection rates and inversely related to confirmed virus death rates,” 32 due to greater adherence to social distancing practices and better quality of health care in cities.

Outside the US, Asian cities, including Seoul and Tokyo, which have a higher population than New York City, have had much fewer deaths. Large, dense urban areas in the Northeast and the Northwest were the first to become the hotspots not because they are densely populated, but because they were transportation hubs where infected people entered the country. Since the summer, some of the least densely populated states in the country have become the hotspots, through infections in meatpacking plants, campaign rallies, and funerals. Contagion rates are more correlated to economic and social relationships than to the density of cities.

Bassett writes that after the recurring epidemics of the nineteenth century, cities made public health measures to optimize urban living.33 Density in cities makes possible the cultural institutions, public transportation, and parks of incomparable quality and scale, while also reducing carbon footprints per capita. Bassett further argues that those who can afford to flee the cities to their suburban and rural retreats during a pandemic should not give up on cities. Instead, cities can reduce risks by providing more frequent trains and buses to reduce crowding, create more parks and spaces for pedestrians, and build more affordable housing.

Pandemic’s Impact on Commuting and Transportation Infrastructures

The pandemic is leaving a profound impact on which and how people commute to work, if they commute at all. In a June 2020 interview, the Stanford economist Nicholas Bloom commented that 42% of Americans were now working full-time from home, whereas 26% are working on-premise and the remaining 32% are not working.34 Of those working from home, the World Economic Forum says that 98% of people would prefer to work from home post-pandemic, citing flexibility in schedule and work location as the top benefits.35 What does this mean for public transportation in cities? And what impact will it have on social and racial inequalities? Those whose jobs require them to commute – many of whom are minority and blue-collar workers – often rely on public transportation. One in five of the poorest US households does not own a personal vehicle.36 In New York City, the number of travelers using public transportation decreased by 95% in the spring of 2020. Between 2019 and July 2020, the ridership decreased nationally by 58% (Fig. 10).37

The fear of infection from COVID-19 is a primary reason for this reduction. However, the number of published studies on infections through public transit is lacking in comparison to those on air travel. Whether the subways and buses can be reliable, well-maintained, and safe is a grave concern when ridership and accompanying income have drastically dropped. Following the pandemic, those with higher income will more easily be able to return to their commute, if they are required to or choose to do so.

A lack of reliable public transportation threatens to result in further inequalities between racial and economic groups.

POLITICS, CULTURE, AND CHALLENGES IN CHANGING HABITS

When diseases spread through ubiquitous elements such as air and water, infection prevention requires radical shifts in people’s perception of the infrastructure that they often take for granted, such as when, where, and how they breathe air or drink tap water. Since the virus-carrying droplets and aerosols are invisible to our naked eyes, changing people’s basic habits, such as breathing and walking, is particularly challenging, as people resist changing established habits and cultures. Japan – where the infection rate has been relatively low – has faced less resistance in mandating face coverings, which is a common practice since childhood when one catches a cold or serves lunch to their peers in classrooms. But we see that people resist unfamiliar habits, and in the US, where the wearing of masks is not customary, face-covering has been harder to mandate. Nowhere has the wearing of masks been so politicized as in the US, where the wearing of masks has become a contentious, political choice, an act of party alignment as much as a public health practice. As David Gissen writes, “air breathed within buildings, like the glass of water drunk in the city, is a site of urban tensions and representations.” 38 Access to infrastructure, including air, is politically and culturally contested. As architects and planners implement designs with long-term impacts, the political and cultural forces require thoughtful negotiations.

ASKING THE RIGHT QUESTIONS

History suggests that public health measures taken as a result of a pandemic will persist as part of a cultural, behavioral alignment and permanent physical infrastructural changes – ranging from healthcare buildings and plumbing to public parks and sidewalks. Past examples of long-term imprints range from some the finest to the most disturbing interventions in urban design. Many infrastructures that have made cities livable and desirable, such as Victoria Embankment in London and Central Park in New York, were built in response to destructive diseases. Conversely, practices such as the mass-demolition of Lung Blocks remain sources of racial inequalities several decades later. As cities make design and policy changes to protect their citizens from the invisible virus, they need to ask how these changes impact social equity and quality of life for all, not just of those in power. How should we critically examine COVID-19’s impacts on roads, learning and working spaces, and the lives of delivery workers as we increasingly depend on digital platforms during the pandemic – from file sharing on Google Drive, to shopping on Amazon and ordering food on DoorDash? Lasting effects on cities are not limited to the physical, but also social and cultural. As diseases such as HIV/AIDS have successfully been treated with drugs combined with the social support of neighbors, COVID-19 must be treated as a physical and social illness. We have yet to see the full impact of the pandemic, and the consequences that are the hardest to predict and prepare for may prove to be the most telling. In order to make cities more livable and equitable, we need to learn from history and ask the right questions as cities move forward with this airborne virus.

Richard Sennett, “Cities in the Pandemic,” Public Space,May 5, 2020, https://www.publicspace.org/multimedia/-/post/cities-in-the-pandemic.

“History of Quarantine,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, July 20, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/historyquarantine.html.

Paul Meurs and Marie-Thérèse van Thoor, Sanatorium Zonnestraal: The History and Restoration of a Modern Monument (Rotterdam: nai010, 2011).

Michel Foucault, Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception (New York: Vintage, 1994).

Jain Malkin, “Healing Environments as the Century Mark: The Quest for Optimal Patient Experiences,” in Architecture of Hospitals, ed. Cor Wagenaar (Rotterdam: NAi, 2006), 258-65.

“Story of Cities #14: London’s Great Stink Heralds a Wonder of the Industrial World,” The Guardian, accessed August 24, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/apr/04/story-cities-14-london-gr....

Lawrence Veiller, Tenement House Reform of New York, 1836-1900 (New York: Tenement House Commission, 1900), 17.

Thomas Fisher, “Frederick Law Olmsted and the Campaign for Public Health,” Places, November 2010, https://placesjournal.org/article/frederick-law-olmsted-and-the-campaign....

Sheri Fink, “Treating Coronavirus in a Central Park ‘Hot Zone’,” New York Times, April 15, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/15/nyregion/coronavirus-central-park-hos....

Sheri Fink, “Treating Coronavirus in a Central Park ‘Hot Zone’,” New York Times, April 15, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/15/nyregion/coronavirus-central-park-hos....

Ibid., 203.

Paul E. Farmer, Bruce Nizeye, Sara Stulac, and Salmaan Keshavjee, “Structural Violence and Clinical Medicine,” PLoS Med 3, no. 10: e449 (October 2006): 1686-91.

Ibid., 1688.

Roberts, Infectious Fear, 221.

Douglas S. Massey and Jonathan Tannen, “A Research Note on Trends in Black Hypersegregation,” Demography 52, no. 3 (June 2015): 1025–34, doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0381-6.

“125 Best Places to Live in the US,” US News and World Report, accessed August 30, 2020, https://realestate.usnews.com/places/rankings/best-places-to-live?src=us....

“Rondo Neighborhood and I-94: Overview,” Minnesota History Center, accessed August 27, 2020, https://libguides.mnhs.org/rondo.

“Rational Use of Personal Protective Equipment for Coronavirus Disease (Covid-19) and Considerations during Severe Shortages,” The World Health Organization, February 27, 2020.

“Physical Barriers for COVID-19 Infection Prevention and Control in Commercial Settings,” National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health, May 13, 2020,

https://ncceh.ca/content/blog/physical-barriers-covid-19-infection-preve....

“Safe Outdoor Activities during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Mayo Clinic, accessed August 29, 2020, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/in-depth/safe....

Alvin Powell, “Is Air Conditioning Helping Spread COVID in the South?,” Harvard Gazette, June 29, 2020, https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/06/air-conditioning-may-be-f....

Jianyun Lu et al., “COVID-19 Outbreak Associated with Air Conditioning in Restaurant, Guangzhou, China, 2020,” Emerging Infectious Diseases 26, no. 7 (July 2020),

LTL Architects and Guy Nordenson and Associates, Manual of Physical Distancing, LTL Architects website, August 10, 2020, http://ltlarchitects.com/blog/2020/6/8/manual-of-physical-distancing.

Aaron Betsky, “Welcome to Our Carless Future,” Architect, https://www.architectmagazine.com/design/welcome-to-our-carless-future_o.

“Wine Windows: Buchette del Vino,” Buchette del Vino, accessed August 30, 2020, https://buchettedelvino.org/home%20eng/home.html.

Jane Jacobs, Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Vintage, 1992). First published in 1961 by Random House (New York).

Ibid., 56.

Ian Klaus, “Pandemics Are Also an Urban Planning Problem,” Bloomberg, March 6, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-06/how-the-coronavirus-c....

“Transformed City: Infrastructure Now,” American Institute of Architects, New York, accessed August 30, 2020, https://calendar.aiany.org/2020/08/12/the-transformed-city-infrastructur....

“Pandemic’s Front-Line Work Falls on Women, Minorities,” CBSNews, May 10, 2020, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/fontline-work-women-minorities-pandemic/.

Mary T. Bassett, “Just Because You Can Afford to Leave the City Doesn’t Mean You Should,” New York Times, May 15, 2020.

Shima Hamidi, Sadegh Sabouri and Reid Ewing, “Does Density Aggravate the COVID-19 Pandemic?,” Journal of the American Planning Association 86, no. 4 (2020), 495-509, doi: 10.1080/01944363.2020.1777891.

Bassett, “Leave the City.”

May Wong, “Stanford Research Provides a Snapshot of a New Working-from-Home Economy,” Stanford News, June 29, 2020, https://news.stanford.edu/2020/06/29/snapshot-new-working-home-economy/.

“COVID-19 Trends Impacting the Future of Transportation Planning and Research,” National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, August 17, 2020, accessed October 18, 2020, https://www.nationalacademies.org/trb/blog/covid-19-trends-impacting-the....

Ramya Vijaya, “Coronavirus Lockdowns Are Pushing Mass Transit Systems to the Brink – and Low-Income Riders Will Pay the Price,” Government Technology, April 14, 2020, https://www.govtech.com/fs/transportation/Coronavirus-Lockdowns-Are-Push....

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, “COVID-19 Trends.”

David Gissen, Manhattan Atmospheres: Architecture, the Interior Environment, and Urban Crisis (Minneapolis MN, USA: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 14.

Figure 1: photo by © Institute for Social History, Amsterdam.

Figure 2: map by © NYC Municipal Library.

Figure 3: photo by © ILO/Minette Rimando.

Figure 4: photo by © Peeradontax.

Figure 5: diagram by Jianyun Lu, et al, “COVID-19 Outbreak Associated with Air Conditioning in Restaurant, Guangzhou, China, 2020,” Emerging Infectious Diseases 26,

no. 7 (July 2020).

Figure 6: photograph by © Roozbeh Rokni.

Figure 7: diagram by © LTL Architects and Guy Nordenson and Associates (2020).

Figure 8: photo by © buchettedelvino.org.

Figure 9: photo by © author.

Figure 10: photo by © Marc Hermann / MTA NYC Transit.

Aki Ishida is an Associate Professor of architecture at Virginia Tech. She is also a Senior Fellow of the Institute for Creativity, Arts, and Technology and the Director of Intelligent Infrastructure for Human-Centered Communities, the university’s trans-college initiative. Prof. Ishida’s work examines architectural materials in broader cultural contexts. She authored the book Blurred Transparencies in Contemporary Glass Architecture: Material, Culture, and Technology (Routledge, 2020). Prof. Ishida received a B.Arch from the University of Minnesota and an MS in Advanced Architectural Design from Columbia University. E-mail: aishida@vt.edu