Professor in Residence, Department of Architecture, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

With the notable uptick of natural disasters impacting densely-populated areas, attention to the subject of urban resilience has increased among ecologists, economists, engineers, social scientists, and designers. But despite an extraordinary cross-disciplinary interest in a single subject, the urban resilience discourse has remained largely siloed by discipline. This essay builds on concepts of resilience from ecology and social science and positions urban design (in itself at the intersection of architecture, planning, and landscape architecture) as uniquely situated for integrating and operationalizing various concepts of urban resilience. The authors propose a socio-ecological urban design approach that bridges natural, human, and spatial systems and is empirically grounded in historical research, field observations, and interviews with informal settler families (ISFs) living along the shoreline of Laguna de Bay in Metro Manila. The findings revealed that while many were affected by regular flooding and issues of housing security, these were not necessarily deciding factors when determining where to live. In response to programs which emphasize out-of-city relocation, authors developed three principles of urban resilience that instead spatially integrate formal and informal communities.

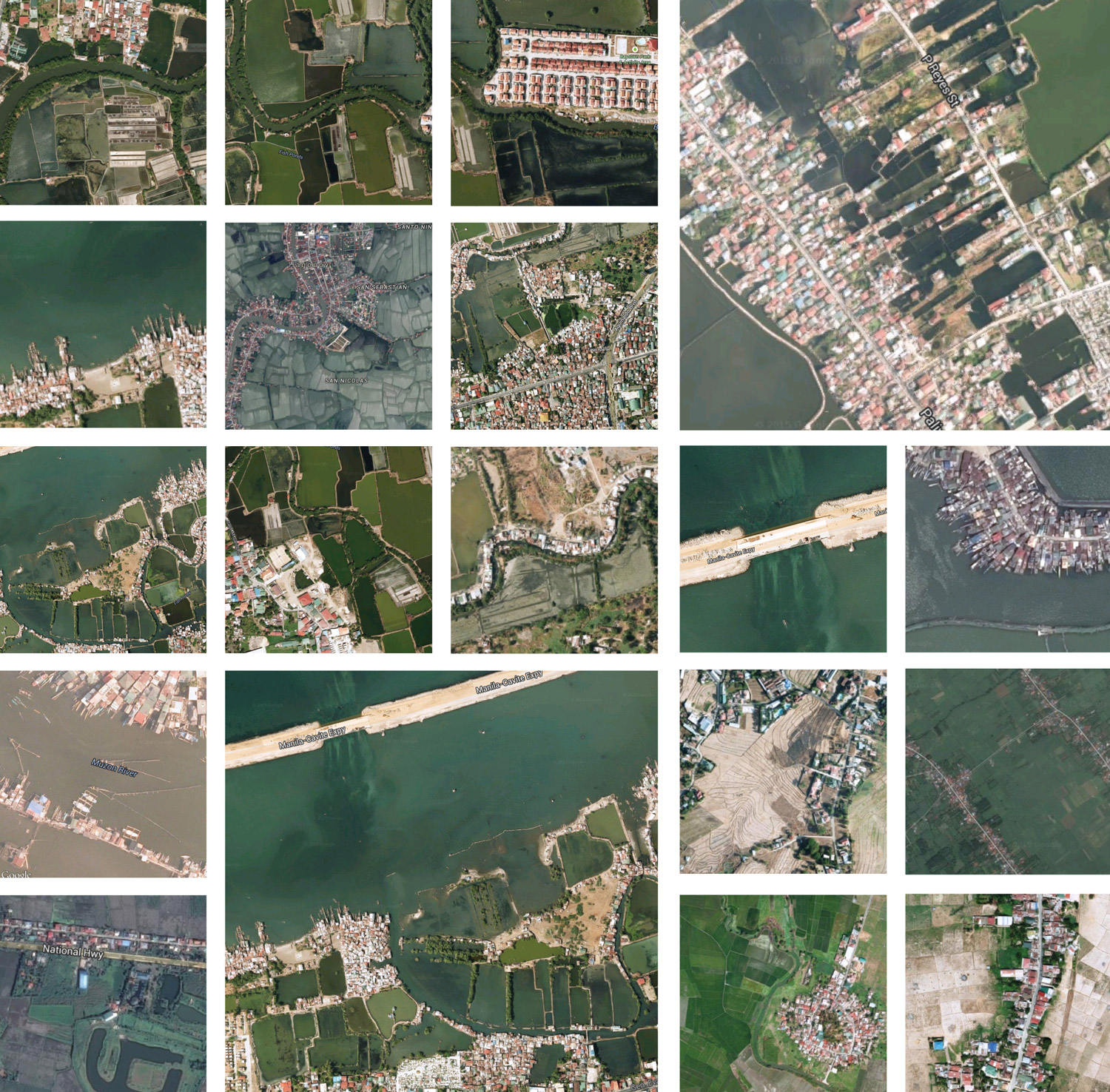

Since 2013, the World Risk Report has consistently ranked the Philippines among the top three countries at risk of extreme natural disasters. Its geographic location also places this archipelago nation within one of four “global hotspots for a high disaster risk… [where] a high level of exposure to natural hazards coincides with very vulnerable societies.” 1 For those living in a country defined by 36.289 km [22,549 mi.] of coastline and an intricate network of streams, rivers, and lakes, the urban poor are the most susceptible to and least protected from the impacts of recurring and intensifying flooding. In this context, the concept of “edge” takes on multiple meanings. In Metro Manila, a mega city characterized by overlapping vulnerabilities, the “edge” is a dynamic water-land interface, a socio-economic delineation, and the spatial distinction between the formal and informal city (Fig. 1).

Until the latter half of the twentieth century, the vast majority of Filipinos lived in rural areas, but from 1975 to 2010 the population of Metro Manila ballooned from 5 million to nearly 12 million. This dramatic rate of growth contributed to the nearly 3 million informal urban dwellers (600,000 informal settler families), living in the metropolis today.2 Many of these migrants were attracted by opportunities to make higher-wages, but they arrived with limited education, training, or support to transfer their agricultural skills into higher-paying jobs.

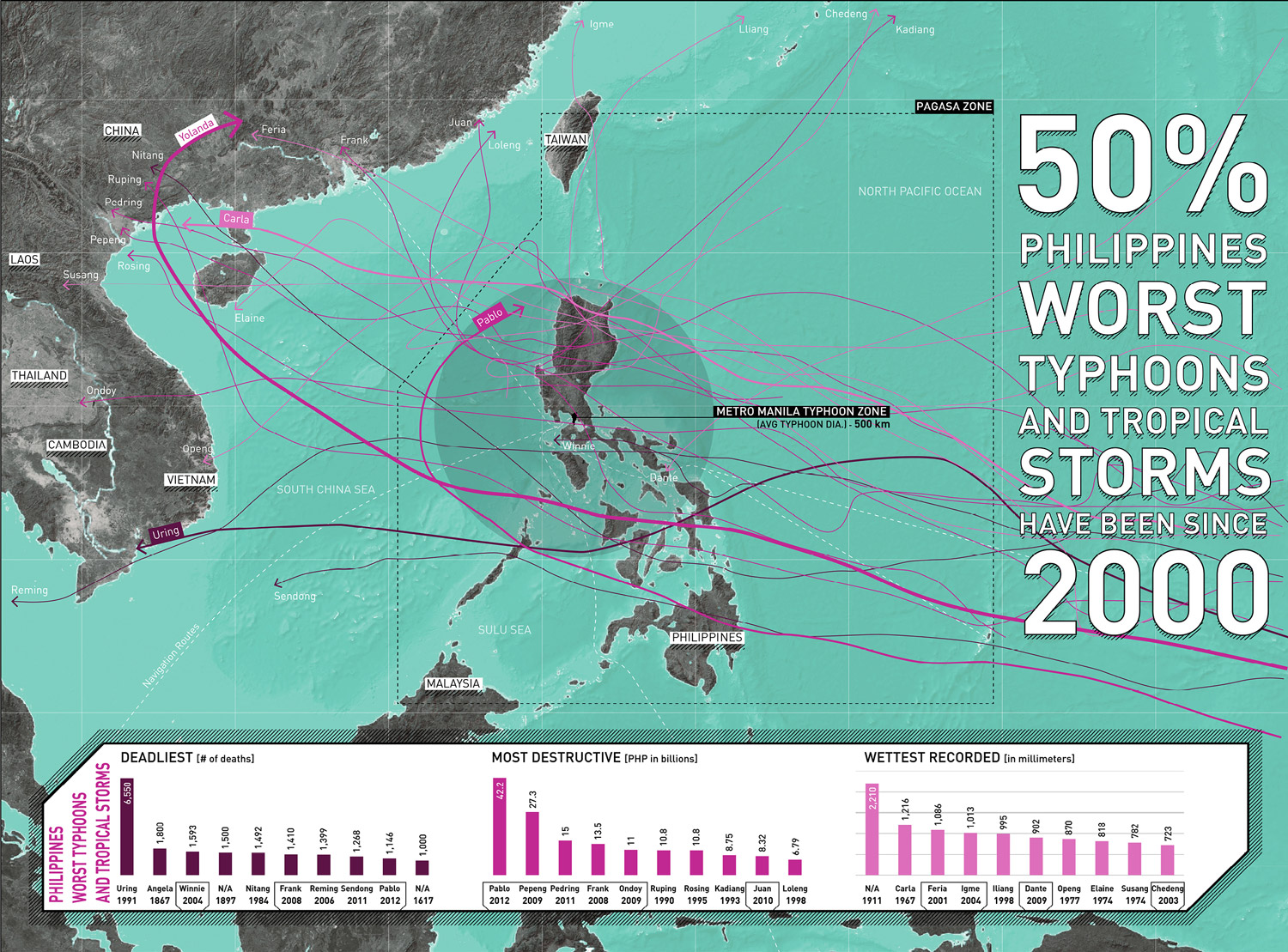

In 2013, Typhoon Haiyan (nationally known in the Philippines as Yolanda) became the strongest tropical storm ever recorded at landfall, killing thousands and displacing hundreds of thousands. Although Typhoon Haiyan did not center on Metro Manila, an average of 11 to 20% of typhoons and tropical storms pass directly over the capital annually, amplifying an already growing focus on disaster preparedness.3 Four years prior to Typhoon Haiyan, the Philippine government established the Climate Change Commission and Climate Change Act of 2009 “to afford full protection and the advancement of the right of the people to a balanced and healthful ecology… to fulfill human needs while maintaining the quality of the natural environment for current and future generations.” 4

Acknowledging the interconnectedness of human and natural ecosystems, the Philippines became a global leader on resilience and climate change policy. However, despite their progress, government programs aimed at protecting communities from the adverse impacts of natural hazards continue to emphasize out-of-city relocation, largely ignoring the pre-existing vulnerabilities faced by certain impacted communities; those which, when left unaddressed, can exacerbate the already devastating impacts of climate change for the city’s most vulnerable populations.

Conceptual Framing: Urbanism as Society, Nature, and the Built Environment

An average of twenty typhoons touch down in the Philippines each year, with fifty of the worst typhoons and tropical storms in the country’s history having occurred since 2000. These storms pose especially high risks to informal urban dwellers living within the boundaries of the metropolis along waterways and shorelines (Fig. 2).5 With the notable uptick of natural disasters impacting densely-populated areas, attention to the subject

of urban resilience has increased among ecologists, economists, engineers, social scientists, and designers. But despite an extraordinary cross-disciplinary interest in a single subject, the urban resilience discourse has remained largely siloed by discipline. Literature that bridges design and resilience has mostly responded to a critique of design as being overly “in the service of narrowly defined human interests but having neglected its relationship with our fellow creatures.” 6 And while this ecologically-based critique of urban design is important, it has resulted in an overemphasis on ecological environmental considerations at the expense of socio-spatial factors which also determine resilience for complex and ever-changing societies.

Cities are palimpsests. They are the spatial manifestations of a layering and re-layering of social and environmental systems over time. While urban design has been described as “an incompletely theorized project” and conceptualized in terms of “urbanistic action” by Alex Krieger and “operational taxonomy” by Joan Busquets and Felipe Correa, at its most basic level, “the function of urban design, its purpose and objective, is to give form and order to the future.” 7 In this essay, the authors explore an intellectual space that geographer Matthew Turner describes as “the complex interactions of history, human livelihood practices and ecological response in particular places” in order to gain a deeper understanding of the latent potential in working at the intersectionality of human and natural systems and to design more resilient urban places.8

With Metro Manila as a backdrop, this essay aims to address a gap in urban resilience literature by building on concepts of resilience that come from both ecological and social science perspectives, and positioning urban design (which itself is rooted in the synthesis of architecture, planning, and landscape architecture) as a uniquely situated discipline for integrating and operationalizing various concepts of urban resilience.9

In an attempt to establish urban design’s role as a bridge between disciplines that can comprehensively address resilience issues, the authors propose a “socio-ecological urban design concept of urban resilience”:

•The ability to overlap place-based and sector-specific urban networks, systems, and communities that operate across temporal and spatial scales such that they can anticipate and absorb disturbances and either persist as they are, or rapidly transition or transform to more desirable states.

The development of this concept is empirically grounded in historical research, field observations, and interviews with informal settler families (ISFs) living in Metro Manila. When discussed in this paper, “sector-specific vulnerabilities” refer to the socio-economic stressors on ISFs (including network fragility, land insecurity, and social and economic isolation).

“Place-based vulnerabilities,” which traditionally refer to ecological environmental hazards (such as earthquakes, volcanoes, typhoons, tsunamis, and regular flooding), are expanded by an urban design lens to also include spatial liabilities (describing built environments characterized by chaotic patchworks of development from decades of laissez-faire and unregulated planning practices, and rooted in a socially and spatially exclusive design legacy). The authors were particularly interested in new forms of urbanism that could be imagined at the intersection of:

1.ecological environmental factors related to the impacts of environmental degradation;

2.socio-economic factors related to the interface between formal and informal economies; and

3.morphological factors related to spaces that physically separate the urban poor from other sectors of society.

Typhoon and tropic storm routes in the Philippines move from the southwest toward the northeast, sometimes making their way through the National Capital Region of Metro Manila. With increasing frequency and severity of storms events in the last fifty years, Metro Manila’s low-lying coastal location continues to be vulnerable to extreme flooding.

Grounded Theory: Qualitative Research, Spatial Analysis, and Conceptual Design

Cities are only as resilient as their most vulnerable citizens. In Metro Manila the most vulnerable citizens are the urban poor who occupy the social and spatial edges of society between development and infrastructure, or along rail lines, riverbeds, easements, or flood zones.10 Challenging past assumptions that out-of-city relocation is the most resilient solution for ISFs, authors researched the morphological underpinnings of social and spatial divisions in Metro Manila, directed field studies to better understand legacy and emergent vulnerabilities, evaluated failed relocation policies and programs, and explored alternative vulnerability-reducing strategies in four barangays in Muntinlupa City - barangay is the native Filipino term for neighborhood, district, or ward and the smallest official administrative division used in the Philippines (Fig. 3).

Shifting across the regional and city context, Muntinlupa is situated between dynamic geographic forces: (a) Muntinlupa is the southernmost city in Metro Manila and sits between Manila Bay and Laguna de Bay, the largest freshwater lake in the Philippines; (b) four barangays investigated for the World Bank’s Citywide Development Approach for Informal Settlement Upgrading include: Sucat, Cupang, Buli, and Alabang. Located between the Philippine National Railway and Laguna de Bay, many informal settlements rely on the railway and fishing for their economic wellbeing.

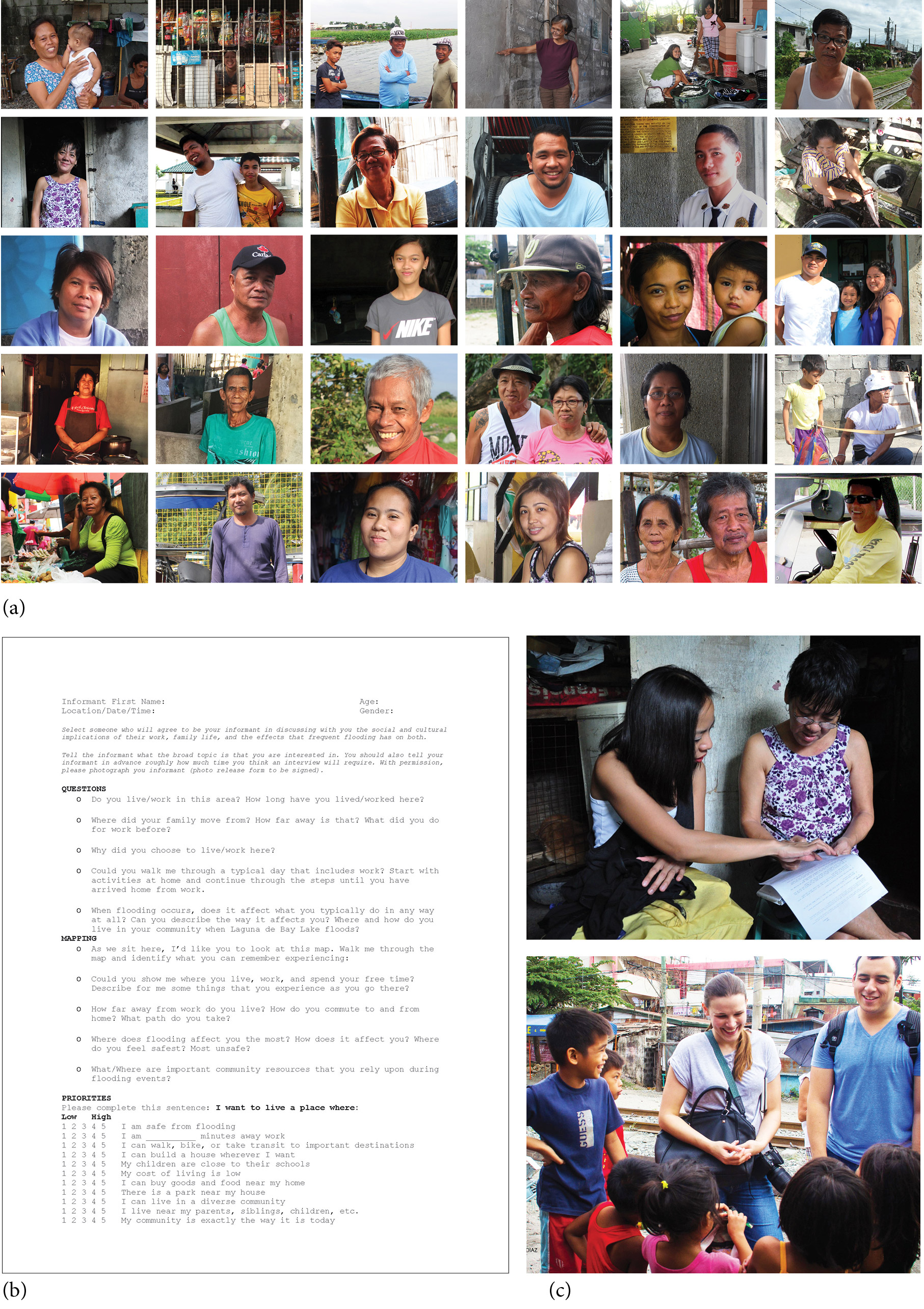

The authors used snowball sampling techniques to identify and interview forty informal urban dwellers living along the shoreline of Laguna de Bay as well as representatives from community-based organizations, government agencies, designers and developers, and International NGOs. Findings revealed that while many ISFs were affected by regular flooding and issues of housing security, these were not necessarily the deciding factors when determining where to live. These findings were supported by the investigations of Dr. Emma Porio and Benvenuto Icamina (discussed later in this paper) who have also explored the intersectionality of informality and resilience in Metro Manila.

The authors synthesized data gathered from field research, interviews, and spatial analysis to develop three principles for resilient urbanism that address the intersectionality of natural, human, and spatial systems. These principles aim to illustrate the virtues of bouncing forward through transformation and innovation rather than bouncing back to the realities of what Dr. Lawrence Vale describes as an increasingly “diatonic equilibrium,” which does nothing to remedy pre-disaster vulnerabilities.”11 These include the following:

1.Ecological environmental principle: Design with nature, not against it

2.Socio-economic principle: Support a shared economy

3.Morphological principle: Break down development silos

Urban design concepts were developed to illustrate the latent potential in integrating formal and informal communities living along the shoreline of Laguna de Bay in Muntinlupa City. Concepts (or “imaginaries”, as they are described in this essay) were intended to be contextually specific and at-the-same-time more broadly applicable frameworks for reducing vulnerability and imagining more ecologically, socially, and spatially resilient edges.

URBAN RESILIENCE AND URBAN DESIGN

Urban resilience generally refers to the abilities for those living in cities (areas with 50,000 or more people) to persist, transition, or transform in the face of disruptions.12 It is a concept that draws from a wide range of disciplinary perspectives, and describes the stable intersection of “governance networks,” “metabolic flows,” “built environment[s],” and “social dynamics.” 13 Theoretically, urban resilience relates to any one system as much as it does to the dynamic interplay of multiple systems; but in practice, overly simplistic interpretations have tended to focus more on protecting city-wide physical, cultural, or economic infrastructures against the threats and impacts of natural hazards than on sector-specific human considerations. This raises two critical concerns. First, it situates vulnerabilities to natural hazards as those most worthy of our attention. Second, it fails to distinguish among the wide range of other vulnerabilities impacting different communities.

In “Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation in Metro Manila,” Dr. Emma Porio connects social vulnerabilities that are specific to informal settler communities living in Metro Manila to ecological factors related to environmental degradation, arguing that without consideration for both sector-based and place-based factors, projects aimed at reducing vulnerabilities can actually hurt more than help the urban poor.

In a sense, government initiatives towards enhancing the environmental, economic and social security of its cities also pose contradictory challenges to the environmental security of informal settlements and the human security needs of its most vulnerable population, the urban poor.14

Designing for resilience begins with identifying and distinguishing among vulnerable communities. In 2015, Dr. S. Atyia Martin developed a Social Determinants of Vulnerability Framework which “focuses on the social, community, and (household) economic social factors… of resilience.” 15

Her research mapped and analyzed the characteristics of vulnerable communities living across a city, identifying hotspots where certain populations experienced high coincidences of overlapping vulnerabilities. Martin found that the most socially vulnerable communities were often more spatially and geographically isolated as well, and she concluded that successfully addressing any one vulnerability required tackling them all.

Distinct from the concept of sustainability which assesses a system’s capacity to persist over time, resilience is a value-based proposition which requires acknowledging that not every future scenario is ideal (nor even possible). Deciding what is right, best, or worth sustaining means asking questions like “resilience for whom and from what to what?” and working with a fully integrated cross-systems perspective.16 However, most concepts of resilience are positive (as opposed to normative), describing measurable conditions (rather than imagining alternative futures).17 Ecologists measure resilience with primarily place-based metrics related to nature, while social scientists rely more heavily on sector-specific metrics related to people. In the context of the Philippines, where natural hazards directly and disproportionally impact vulnerable communities, both views are necessary but neither alone is sufficient.

For urban designers responsible for “[giving] form and order to the future,” urban resilience happens at the intersection of place-based and sector-specific systems.18 It is both descriptive and operative, involving procedures that are simultaneously analytic, value-based, and action-oriented. Despite the plural nature of urban design “in scale, time, property, agency, and form,” few urban design scholars have attempted to connect both natural and social systems (at the same time) to the making of urban form.19 In Design with Nature, Ian McHarg overlaid the values of nature and culture, connecting fluvial performance to human experience and delineating spaces for either development or nature.20 In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs advocated for a particular scale and character of urban fabric to support a diverse social ecosystem of interests, activities, and people.21 Kevin Lynch attributed the organization of urban spaces to the constant thrust of social, economic, and political advancement in Good City Form, and in Justice, Nature, and the Geography of Difference David Harvey defined a “just social order” as one that results in equitable social and spatial relationships between people and the environment.22 More recently, in his 2017 manifesto The Largest Art: A Measured Manifesto for Plural Urbanism, Brent Ryan characterized urban design as an ongoing process and as the spatial and formal orchestration of multiple systems.23 Though framed differently, each scholar understood either ecological or social systems as interrelated and interdependent with built systems. And while their scholarship collectively empowers urban design with agency to envision more resilient cities, it also exposes urban design’s potential culpability in contributing to, even validating, many of the problems which it now aims to address.

DESIGNING THE EDGE IN METRO MANILA

The Making of a Dual City

Metro Manila’s urban landscape is defined by scattershot developments and expressed in dialectics of rich and poor, slum and subdivision, formal and informal, exclusive and accessible, and always pushing the urban poor to the edges of mainstream domestic and civic life. These socio-spatial separations can be traced back to Spanish colonization, American occupation, and even more recently in Filipino-directed urban projects. In the sixteenth century, the Spanish established Intramuros, the colonial capital for the Philippines codified in the Law of Indies as a grid of streets, plazas, churches, government buildings, and houses for the elite. Although informal settlements did not exist as we know them today, there were clear and deliberate physical, social, and class distinctions between the Spanish elite living “inside the city walls,” and the Chinese, Japanese, and Filipinos of Extramuros (arrabales) living “outside the city walls.” 24 In many ways, the design of Intramuros marked the origin of many of the formal and informal distinctions that we can see in Metro Manila today. Following 333 years of Spanish rule, the 1898 Treaty of Paris ceded the Philippines to the United States, and by 1905, Daniel Burnham had already developed a new vision for Manila in the tradition of the City Beautiful movement. Further fortifying the sectoral divisions established by the Spanish, Burnham’s design laid the groundwork for replacing a moat with a golf club, allowing the new American occupiers to substitute physical barriers with economic ones.25

Gated Communities, Exclusive Malls, and Private Infrastructure

Although more ubiquitous today, the divisive edges of contemporary Metro Manila are no less pernicious. Post-World War II private development has produced securitized islands in the form of gated communities, walled off from the greater metropolis and designed to limit access. An ever-growing demand for private housing and exclusive malls in urban and peri-urban areas has far outpaced the building of the infrastructures and services necessary to support them. This has led many public works departments to rely even more heavily on private sector actors for public infrastructure, making it increasingly harder to effectively regulate new developments (Fig. 4). The result has been a growing privatization of public streets and throughways, and developments characterized by a “network of elite spaces, with proliferating citadels (e.g. gated subdivisions, luxury condominiums, high-rise office buildings) linked to spaces of elite consumption (e.g. exclusive malls, recreational areas that are fenced-in or simply forbidding to the poor) through toll-highways and flyovers, equipped with high-technology telecommunications, and power and water infrastructures, that hardly extend into the public city.” 26 This geographically sprawling version of the Intramuros-Extramuros dyad has ultimately relegated the urban poor to areas with high exposure to flooding and limited access to even basic services.27

Private and public transportation: (a) the privatization of road infrastructure reduces mobility options and contributes to incredible traffic congestion along primary public roads, further fragmenting connectivity within Metro Manila; (b) jeepnies, the popular mode of public transportation, are often not allowed in private enclaves and roads, contributing to more congestion.

“The Economics of Informal Settlements” revealed that that most informal urban dwellers are self-employed, working either in or near their homes. Many own sari-saris (neighborhood variety stores), work in transportation or construction, or operate home laundry services (Fig. 5). Between this patchwork of domestic enclaves, large and often exclusive malls have become prototypical centers for both commerce and public life. But with as many as 75% of all workers in the Philippines employed informally, these centralized and highly controlled urban spaces have hurt more than helped the urban poor.28 For those relying on more spatially dispersed and economically diverse networks, even the most beautifully designed malls come at a high social price, limiting the chances for many small and medium sized enterprises to survive. From an ecological perspective, privatized water, drainage, and sewage infrastructures that protect malls from flooding can increase flood vulnerability for surrounding areas.29 Impermeable footprints of big-box typologies, paved parking lots, and the siting of buildings on or near waterways often constrict the flow of streams, creating problems associated with flooding in other locations (Fig. 6).

Commercial development poses major challenges: (a) Festival Alabang, a large mall with surface parking lots, is constructed on the Alabang River in Muntinlupa; while one kilometer to the east, informal settlements reside on the Laguna de Bay marge, selling goods along the north-south corridor of Ilaya Street; (b) Existing development patterns contribute to environmental hazards by encroaching on river edges and adding to impervious surfaces.

Informal Settlements: Living on the Edge

The World Bank organizes informal settler families (ISFs) into three categories:

1.those living on government land;

2.those living on private land and in threat of eviction; or

3.those living in danger zones.30

In 2014, approximately 18% of the 600,000 ISFs in Metro Manila were living both without legal claim and in primarily high-risk areas. While there is no direct translation for the term “slum” in Tagalog (the official language of the Philippines), the term iskwater refers to squatters living in semi-permanent dwellings (Fig. 7). Other terms such as estero (estuary, creek), looban (tightly-packed inner blocks invisible from the street), dagat-dagatan (flood prone land), and eskinita (narrow lane) are also often used to describe the physical geographies of informal settlements. There are six typical informal settlement typologies in Metro Manila.

In Muntinlupa City, informal settlements are located along the shoreline of Laguna de Bay, the esteros, and the West Valley Fault, making communities vulnerable to flooding and earthquakes. In 2009, Tropical Storm Ondoy would devastate Muntinlupa with flooding along the lakeshore; however, many informal settlements have continued to make their homes on this high risk land today.

These include the following:

●Coastal or lakeshore settlements (Tabing-Dagat). Water-based settlements are home to rice farmers and fish harvesters who often rely on water for their livelihoods. They are commonly found along the edges of Laguna de Bay in Muntinlupa City and are often subject to the most intense flooding.

●Esteros and riverbank settlements (Tabing-Ilog).

Settlements along esteros (estuaries or creeks) and riverbanks are also common throughout Metro Manila. They occur within a ten-meter [32.8 ft.] easement along both sides of major waterways, where development can constrain water capacity and flood during heavy rains and storms, endangering the lives of residents.31

●Vacant land and railway settlements (Along the riles).

Some settlements occur on land that is either held by an absentee landlord or earmarked for future uses. In some cases, such as the Philippines National Railway right-of-way, these spaces functions as a main streets but can be narrow and unsafe for human settlement.32 Other settlements such as those in the Cristo El Salvador Cemetery, encroach on spaces that are designated for other uses.

●Inner block settlements (Looban).

In the densest sections of Metro Manila, such as Intramuros and parts of Alabang, settlements crowd in the inner courtyards of urbanblocks. They are often invisible from the street and only accessible through narrow lanes and passageways.

●Settlements near exclusive villages (Gillages).

These settlements emerged after the 1920s when elite families moved out of Intramuros to suburban enclaves and villages. “Gillages” (from the colloquial merger of the words gilid meaning “side,” and village) collocate alongside elite villages to provide domestic services.33

●Settlements near the dump (Barangay Basur).

Many settlements are located near dump sites which serve as resources for scavenging and recycling.34 The infamous Smokey Mountain, an unplanned dumping site from the 1950s, grew to a city of 30,000 people by the 1980s, with scavengers relying on selling and recycling goods found within the site. Though Smokey Mountain was leveled and 20 ac. [8 ha] were redeveloped with housing by 2001, several settlements in Metro Manila still rely on dump sites as sources of income.35

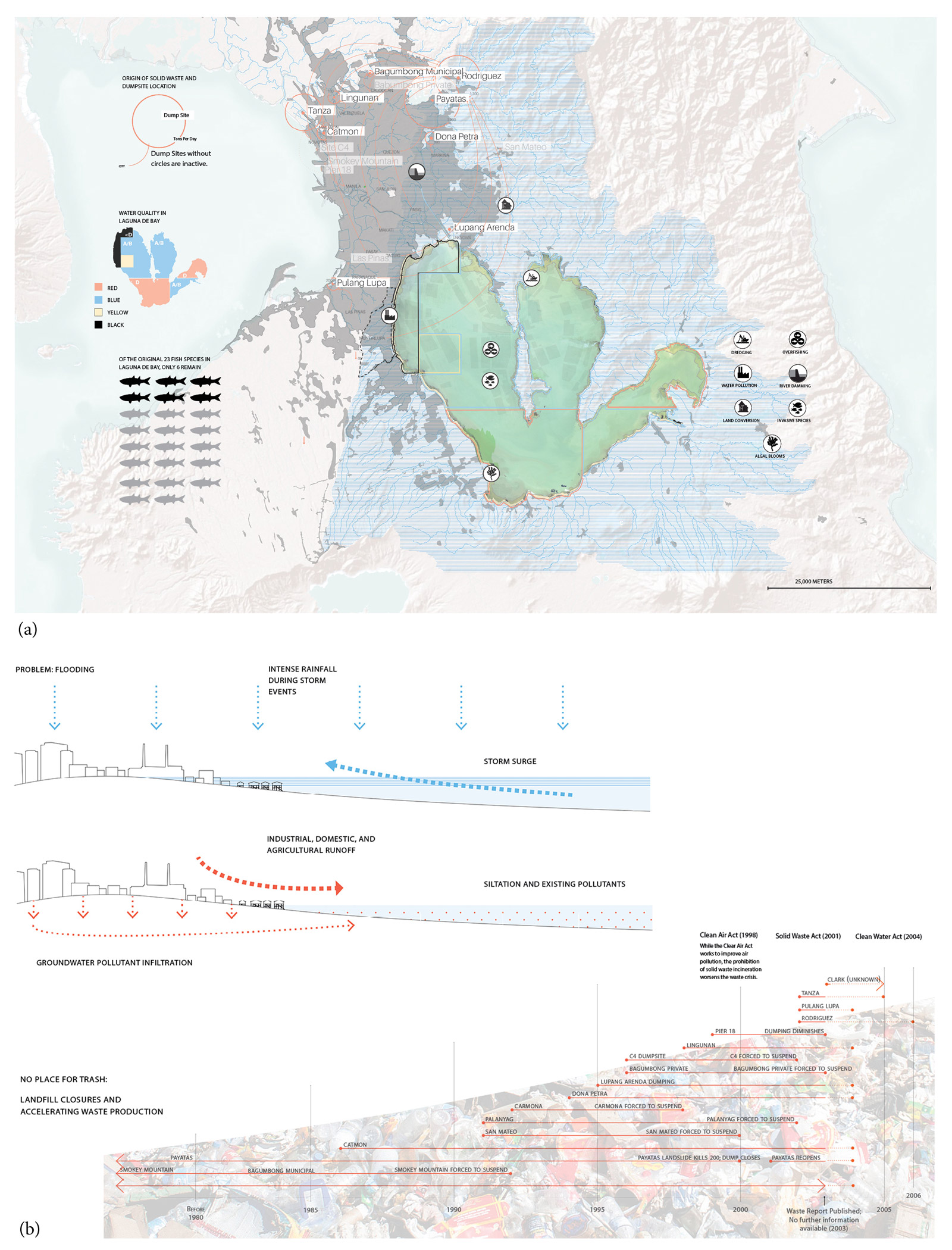

Discussion: The Challenge of Resettlement as a Strategy for Resilience

In Metro Manila, approximately 6.000 tons [6,613 US tons] of trash goes into waterways, landfills, or streets every day. This trash leaches into soil and the sub-basin of Laguna de Bay resulting in “Worse than Class D” water quality along the shoreline of Muntinlupa City on a level of toxicity which is considered unsafe for human contact of any kind.36 Overfishing, invasive species, and decreased saline levels from over-damming have also had negative impacts. Trash removal strategies such as dredging aimed at improving water quality have actually had adverse effects, exacerbating ecological damage by stirring up silt which harms fish populations (Fig. 8).

To make matters worse, these flood-impacted areas in Metro Manila are projected to increase to 42% by 2050, and affecting nearly 2.5 million people living in low-lying areas by 2100.37 All of these issues pose serious health risks for lakeshore and estero communities, but despite the known risks, local fisheries remain major sources of food and income for these communities, and so informal dwellers continue to live in basket-like bamboo houses stilted above the contaminated water and closer to their social networks and sources of income.

Lake contamination and pollution contribute to the ecological environmental vulnerabilities of Informal Settler Families: (a) Laguna de Bay’s “Worse than Class D” status has lake pollution attributed to domestic, agricultural, and industrial sources, which has depleted fish to only 6 species remaining of the original 23; (b) two major sources of flooding include obstructed waterways caused by intense rain fall during storm events and storm surge, and urban development, waste, and runoff. A historic timeline of landfill events show that waste production is accelerating, though there are also increasing regulations to curtail pollution.

Prior to 2011, the Philippine government was moving aggressively to reduce the prevalence of informality in Metro Manila, primarily by relocating urban poor communities from hazardous areas in the city to the outskirts where land was cheaper and more readily available. Many were relocated with little to no meaningful community engagement, leading dislocated families to experience unsustainable mortgage debt, increased travel time and loss of productivity, and fragmented social and economic networks. In extreme cases, distant relocations have precipitated breakdowns in traditional family units, where breadwinners live apart from their families for extended periods of time in order to be closer to their places of employment. In his 2015 post-Typhoon Haiyan visit, Pope Francis vocalized this issue:

The pressures on family life today are many. Here in the Philippines, countless families are still suffering from the effects of natural disasters. The economic situation has caused families to be separated by migration and the search for employment, and financial problems strain many households.38

Learning from failures of the past and leaving out-of-city relocation as a measure of last resort, the Philippine government launched Oplan Likas in 2011 to move 104,000 ISFs out of ecologically hazardous areas and into safer and higher density urban housing. From 2011 to 2016, P.50 billion (approximately US$1.5 billion) was allocated for land acquisition and construction. But the pace of implementation has severely lagged behind demand, leading to a backlog of approximately 1.7 million shelters in 2016, as estimated by The Housing and Urban Development Coordinating Council. Oplan Likas not only failed to resettle hundreds of thousands of urban poor residents, but also fell short of successfully engaging with those who were resettled in order to understand their aspirations for an improved quality of life . During the same period, some Local Government Units (LGUs) demonstrated more sensitive approaches to resettlement, but they were limited by land constraints, affordability issues, and institutional challenges.39 Examples of community-driven upgrading projects led by NGOs have occasionally won government support, but even those have subsequently failed to scale up due to resource constraints. Private sector participation in the low-income housing market has also been limited to date, though some developers are beginning to recognize an “untapped market opportunity” and to tacitly express interest in expanding their business models to include in-city medium-rise buildings for the urban poor.40 For those living on the social, economic, and physical edges of society, barriers to traditional financing have made it extremely difficult to gain secure housing. This is particularly true for those that primarily depend on the informal economy for their livelihoods.

When considered together, these failures amount to a compelling case against vulnerability-reducing strategies that rely too heavily on flood risk reduction as a primary measure for resilience. Without more comprehensive approaches, such solutions, well-intentioned as they may be, will continue to disconnect vulnerable communities from their social and economic networks and reinforce existing socio-spatial divisions that define Metro Manila as a dual city.41 Acknowledging a need to invest in community-driven decision-making and a financially sustainable model, the World Bank launched the Metro Manila Citywide Development Approach to Informal Settlement Upgrading (CDA) in 2014. The CDA program was created to explore new models for in-city relocation, and more importantly, prioritize community engagement throughout the process. The three pilot projects were: Caloocan City (neighborhood scale), Muntinlupa City (district scale), and Quezon City (city scale).

TOWARDS A MORE RESILIENT URBANISM: THE CASE FOR MUNTINLUPA CITY

Taking the World Bank’s CDA brief as a point of departure, in this section authors explore a socio-ecological urban design approach to resilience in Muntinlupa. The City of Muntinlupa is the southernmost city of 16 LGUs that make up Metro Manila. In 2015, the Muntinlupa City Planning and Development Office estimated that nearly half of the 504,509 residents belonged to the urban poor sector, which is defined by the 1994 Social Reform Agenda as those living under the poverty line and with less than the “Minimum Basic Needs (MBN)... in terms of a three-tier needs hierarchy: survival (food/nutrition, health, water/sanitation, and clothing); security (shelter, peace, income, and employment); and enabling (basic education/literacy, people’s participation, family care, and psycho-social indicators).” 42

In 2007, over 27,000 informal settler families (according to the government definition, there are 5 informal settlers per informal settles family) were living in 241 communities in Muntinlupa; and in 2014, roughly 30% of these were either situated along creeks/esteros (where approximately 5,000 ISFs live), or along the 11 km [6.8 mi.] lakeshore of Laguna de Bay (where approximately 4,000 ISFs live).43 The four most prevalent informal settlement typologies observed in Muntinlupa were: lakeshore settlements, esteros and riverbank settlements, vacant land and railway settlements, and looban or inner block settlements (Fig. 9).

Four major informal settlement typologies found in Muntinlupa included: (a) coastal and lakeshore settlements along Laguna de Bay; (b) vacant land and railway settlements situated along the Philippines National Railway; (c) esteros and riverbank settlements throughout the city; (d) looban or inner block settlements nested within formal development.

Research Methods

In order to better understand the factors affecting the choice for residential location by the ISFs, authors and researchers conducted in-person interviews with 40 informal urban dwellers living along the edge of Laguna de Bay in barangays Sucat, Cupang, Buli, and Alabang (Fig. 10). They were particularly interested in understanding the relative importance of flooding to ISF decision-making processes when determining where to live. Respondents were asked to complete the following sentence: “I want to live in a place where__________” with 10 pre-selected answers that they rated on a scale from 1 to 5 based on significance to their lives. Of the interviewees, 17 were female, 17 were male, 2 were married couples, and 4 were children (surveys with children under 14 were not included). The 36 tabulated interviews included representation by nearly 1% of the estimated 4,000 lakeshore ISFs in Muntinlupa City. Survey results (Table 1) revealed three consistent themes:

1.Proximity and Network.

Community members emphasized the importance of living close to their jobs, schools, sources of food, and transportation options.

2.Housing.

Despite expressing dissatisfaction in their current housing conditions, issues of housing stability and land tenure were still ranked lower on their list of concerns.

3.Flooding.

Very few interviewees described flooding as more than a nuisance.

As found in Icamina’s investigation in the book chapter “The Economics of Informal Settlements,” most interviewees worked in or near their homes, reducing travel time and cost, and making it possible for them to spend most of their time close to their families, friends, and community networks.

Most striking was the relatively lower levels of concern about housing quality and regular flooding. While respondents described these as a unpleasant, they consistently ranked the importance of living in proximity to resources and employment higher. In Dr. Emma Porio’s 2014 research entitled “Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation in Metro Manila,” she also noted that although informal settlers recognized the risks of floods to their homes and communities, a majority of respondents were more concerned with economic problems related to unemployment and a loss of income.44

| Barangays | ||||||

| Sucat | Buli | Cupang | Alabang | Averages | ||

| 1 | I can buy goods and food near my home | 5 | 4.66 | 5 | 4.33 | 4.75 |

| 2 | I can walk, bike, or take transit to important destinations | 5 | 4.33 | 5 | 4 | 4.58 |

| 3 | My children are close to their schools | 4.66 | 4.66 | 5 | 4 | 4.58 |

| 4 | My cost of living is low | 4.33 | 4.33 | 4 | 3 | 3.92 |

| 5 | I live near my parents, siblings, children, etc. | 3.33 | 3.33 | 5 | 3.33 | 3.75 |

| 6 | I am safe from flooding | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2.33 | 3.58 |

| 7 | I can live in a diverse community | 2.66 | 3.33 | 4.66 | 2.33 | 3.25 |

| 8 | There is a park near my house | 3 | 4.33 | 2 | 2.66 | 3.00 |

| 9 | I can build a house wherever I want | 3.33 | 4.33 | 1.33 | 2 | 2.75 |

| 10 | My community exactly the way it is today | 2.33 | 0 | 4 | 2.33 | 2.17 |

Principles of Resilient Urban Design

Although respondents in all three studies (Icanmina’s, Porio’s, and this investigation) consistently ranked flooding below other concerns, these findings in no way diminish the seriousness of health and safety risks associated with regular flooding and standing water. In this section, authors explore three urban design principles aimed at reducing vulnerabilities for ISFs living on the “edge” in Muntinlupa City by asking the following questions:

•How can integrated resettlement strategies balance considerations for natural systems, city form, and socio-cultural dynamics?

•How can ISFs in Metro Manila be better prepared for future storm events?

•How, where, and for whom should future development occur?

•What are the benefits of public, private, and nonprofit sector collaborations?

Responding to stakeholder interviews (Table 1 and Appendices A, B, and C) and vulnerabilities assessments, three principles of urban resilience were developed and illustrated by urban design concepts (“imaginaries”) that operate across scales, time, and disciplinary boundaries (Table 2).

They intentionally blur the boundaries between ecological, social, and spatial phenomena and aim to demonstrate the latent potential in taking a socio-ecological urban design approach to resilience that imagines more efficient, equitable, and integrated urban environments.

| “IMAGINARIES” | ||||

| Scale | Strategy | Morphological | Socio-Economic | Ecological Environmental |

| Neighborhood | Strategy 1: Intelligent Infrastructure Addressing Permanent Temporariness |

Target in-situ and cost-effective shared infrastructure to meet basic needs with community amenities (plumbing, trash, electricity, refrigeration) | ISFs are not relocated and remain in place with proximity to existing social networks and sources of income | Flood-resistant and easily maintained; Human activities are spatially concentrated for easy clean-up and reduced pollution in and along Laguna de Bay |

| District | Strategy 2: Connected Communities with Higher Ground for Lower Income |

Designate temporary flood-emergency evacuation areas on nearby vacant land; Incent private sector participation with targeted up-zoning and special development allowances |

ISFs remain proximate to homes and near public transportation during flood emergencies; Limited social and economic disruption; On-site educational and vocational facilities as pipeline to permanent housing; |

When developed, vacant land retains pervious areas for storm water recharge |

| City, Region | Strategy 3: Landscape Infrastructure and Sustainable Landfill |

Reconfigure land-making strategy for planned C-6 Expressway Dike as controlled bio-remediation pond from Manggahan Floodway in the north to San Pedro to the south; | Local fisherfolk retain water access for lake-dependent livelihoods; Integrates spaces for small scale fish markets and large scale fish processing, connecting informal and formal programs with spaces to buy, sell, or process the daily catch |

Restores a healthy hydrological system by aligning with inland stream outlets, mitigating inland flooding, and cleaning Class D lake water; Reduces stormwater contamination from trash dumping as well as leaching from sewers and landfills |

| City, Region | Strategy 4: Environmental Zoning and Planned Informality |

Plan and zone for ecologically sensitive land with low development value to support environmentally responsive and socially inclusive growth and development | Rural-urban migrants are directed away from the fringes and into developments with opportunities to capitalize on agricultural expertise; Provides live/work economic opportunities in local (farm-to-table) and regional (chain supplier) food production and sale; Reduces household expenditures by 60%, by reducing food costs |

Environmental Zoning adds value to and protects underutilized land; Ecologically sensitive development patterns integrate storm water, open space, agriculture, and built space |

| City, Region | Strategy 5: Integrated Economies Towards a Future Vernacular |

Reconfigure land-making strategy for planned C-6 Expressway Dike as indigenous land-making (pilapil) designed to respond to fluctuations in water level | New developments connect and blend informal and formal sectors with physical spaces that support productive social and economic exchanges; Local fisherfolk retain water access for lake-dependent livelihoods; ISFs are not relocated and remain in place with proximity to existing social networks and sources of income |

Restores a healthy hydrological system by aligning with inland stream outlets, mitigating inland flooding, and cleaning Class D lake water; Ecologically sensitive development patterns integrate stormwater, open space, aquaculture, and built space |

Ecological Environmental Principle: Design with Nature, Not Against It

Interviews with vulnerable populations living along the lakeshore of Laguna de Bay revealed that regular and recurring flooding can take as long as six months to completely recede. In this context, flooding is as much a social problem as it is a natural process, and informal fishing communities continue to live in areas surrounded by polluted water due to their reliance on the lake (Table 2). Lakeshore communities also face the imminent threat of displacement from the construction of seven landfilled islands planned in order to finance the construction of the C-6 Dike Expressway. Here, the barriers to resilience for ISFs are the limited (often agrarian) skillsets; high cost of food (often greater than 60% of household income); lack of safe and affordable housing alternatives; and the threat of development and displacement.

Environmental zoning and planned informality (Fig. 11): With a growing number of rural migrants moving to Muntinlupa each year, the city has an opportunity to explore socio-ecological land-use and development strategies; protecting and preserving the natural environment and connecting rural migrants to urban employment opportunities. By building on the agricultural skills of migrants and taking advantage of wetter, cheaper land at the edges of the city, an environmental zoning and planned informality strategy could create dense development clusters surrounded by floodable farms and a system of environmental corridors that support ecological health. A shared economy approach developed around urban agriculture could divert rural-urban migrants away from hazards and informal developments and towards new clusters of mixed income housing surrounded by agricultural land. Development patterns would then respond equally to the flow of water and an increasing demand for the production of food. In this scenario, new developments and open space systems perform dual roles as flood-reducing landscapes and social infrastructures, supporting both economic productivity and social development.

Landscape infrastructure and sustainable landfill (Fig. 12): The plan to construct seven manmade islands along the shoreline of Muntinlupa City not only disconnects the fishing communities living along the shoreline from their sources of income and food, but it also threatens to create of a giant moat with “worse than class D” water. However, if constructed responsively, the new lakeshore, landfill, and expressway could form an integrated system for cleaning polluted water. By positioning the islands between existing stream outlets with controlled openings, the moat could instead become a regional-scale stormwater retention and bioremediation area and a system of soft edges within the most contaminated areas of the lake. Stepped filtration terraces could provide redundant flood protections against breach, reduce inland flooding, and become platforms for shared public space with open air markets and fishing access for existing communities. This socio-ecological infrastructure could become a literal and figurative bridge between the informal fishing villages and the formal development which would otherwise displace them.

Socio-Economic Principle: Support a Shared Economy

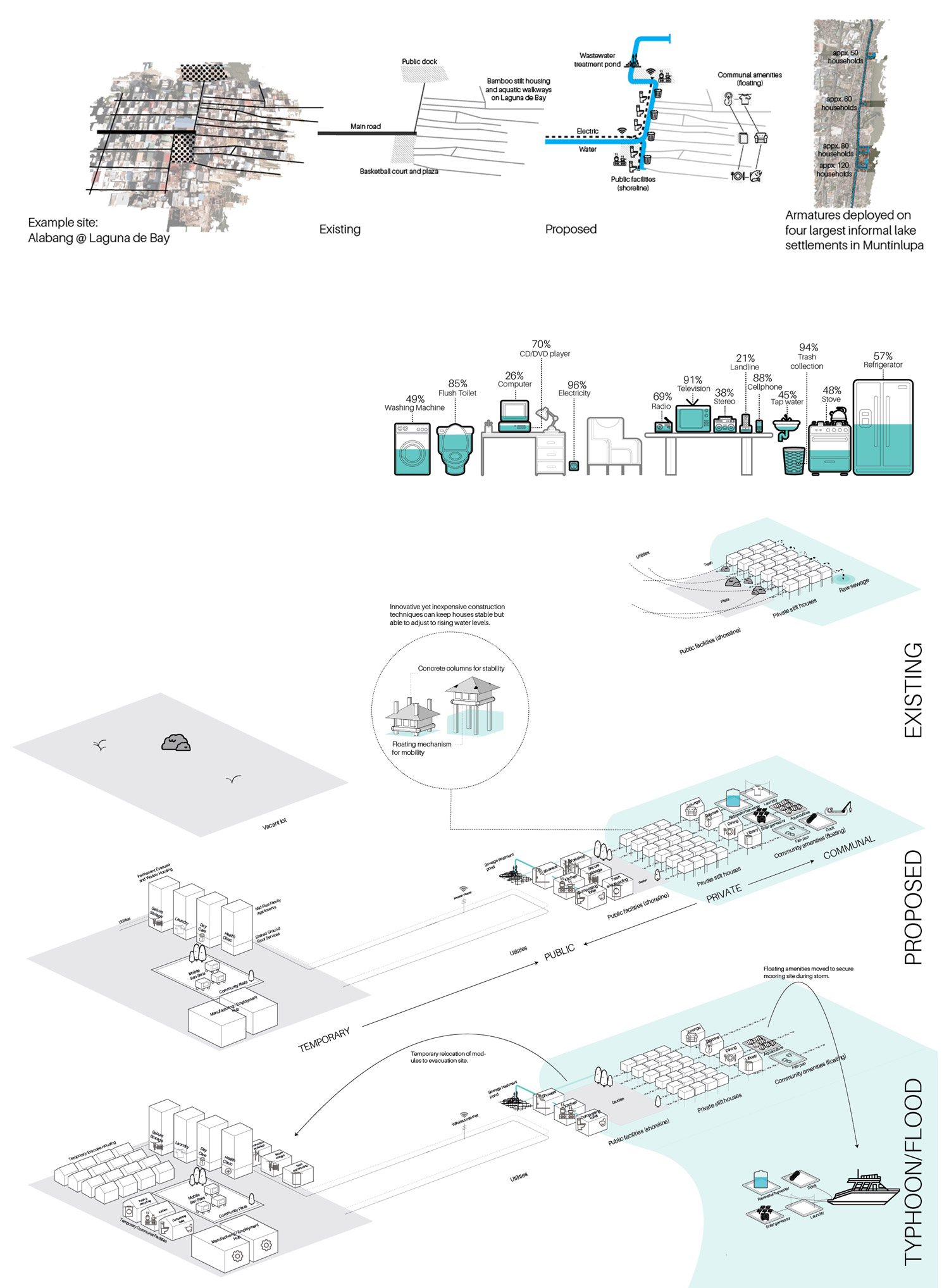

The integration of formal and informal economies could dramatically improve the lives of urban poor residents in Muntinlupa City. Paying close attention to the structural conditions that shape informal settlements, the livelihoods they support, and the social capital that exists within them, informal communities could be improved through tactical and shared infrastructures. Interviews revealed that many informal dwellers rely on proximity to resources and community for their livelihoods (Appendix A), making out-of-city relocation programs largely unsuccessful. Based on conservative 2011 Philippine census estimates for Muntinlupa City, figures showed that at least half of residents lack refrigerators, stoves, clean water, and other basic household amenities. The poorest 15% of residents also lack flushing toilets and adequate trash collection services. Here, the barriers to resilience are a continuous influx of rural migrants to Muntinlupa City; lack of basic household utilities and amenities; insufficient public resources to address informality; and many failed relocation strategies that disconnect families from social and economic resources.

Intelligent infrastructure addressing permanent temporariness (Fig. 13). Formalizing a few basic services for informal communities along a new civic spine could begin to blur distinctions between formal and informal sectors. Rejecting a false dichotomy and exploring ways to ensure a healthy and fulfilling future for all residents, a multifunctional adaptive infrastructure could provide centralized amenities within existing informal communities.

A shared infrastructure could also provide basic services of power, plumbing, refrigeration, and community amenities that reduce vulnerability to flooding, enhance access, improve health and safety, reduce cost, and ultimately incorporate informal neighborhoods as integral parts of the city.

Morphological Principle: Break Down Development Silos

Metro Manila has undergone rapid economic expansion over the past two decades, and this growth has amplified spatial inequities in housing and transportation, environmental deterioration, and the expansion of an informal economy and settlement pattern. The result has been an urban environment which is both physically and socially disconnected and unable to collectively respond to ecological hazards. Here, the barriers to resilience are political, social, and spatial silos among communities; unenforced and uncontrolled zoning and development patterns; uncoordinated public agencies and decision-making; and development that does not accommodate natural systems.

Integrated economies towards a future vernacular (Fig. 14). Borrowing from traditional planning and design technologies and adapting them to the needs of twenty-first century cities, there is an opportunity to reimagine built-up areas to support aquaculture, new forms of inclusive housing, ecologically performative open space, and shared mobility options through culturally rooted land-making. By adapting indigenous construction techniques already visible along the Laguna de Bay shoreline, new patterns for living with water in urban communities could be imagined through morphologies that are both more authentic to Filipino culture and more resilient to Filipino hazards. Development practices such as the pilapil or rice paddy dike (Fig. 15), could inform contemporary construction techniques to be more responsive to regular flooding. Civic projects such as the proposed landfill islands associated with the C-6 Dike Expressway present near-term opportunities to explore new spatial and infrastructural development paradigms. Through new incentives, enforcement of existing regulations, and the design of new edge typologies, the private sector could establish productive relationships between water and land use, as well as between formal and informal developments (Fig. 16).

CONCLUSION

The coincidence of hyper-urbanization, informality, and increasingly severe natural disruptions has drawn broad public attention, triggered the release of large injections of capital, and presented an opportunity (and urgency) to reimagine cities as more connected, adaptive, and resilient. Just as no single strategy can be a silver bullet for resilience, solving for climate change-related vulnerabilities cannot be our only measure for success. Cities are assemblages of deliberate, if uncoordinated, spaces and places embedded with the complexities and contradictions of the communities that occupy them. They serve as both platforms for and expressions of the social life of people and our relationship with nature. Overly simplistic definitions of urban design which emphasize any one system (ecological, sociological, or morphological) over another system will inevitably fall short of achieving a state of resilience that is both socially inclusive and ecologically responsive.

In Aseem Inam’s paper “Meaningful Urban Design: Teleological/Catalytic/Relevant,” Inam describes urban design in the architectural tradition as having “an over eagerness to be unconventional and spectacular” and that it is often taught and practiced as an aesthetic, morphological, novel, and superficial exercise.45

He continues:

Unfortunately, much of this recent interest in urban design repeats the familiar deficiencies of the past: a focus on the superficial aesthetics and the picturesque aspects of cities (instead of what role aesthetics play, say, in community development processes), an over-emphasis on the architect as urban designer and an obsession with design (instead of a more profound interdisciplinary approach that addresses fundamental causes), an understanding of urban design primarily as a finished product (instead of an ongoing long-term process intertwined with social and political mechanisms) and a pedagogical process that is comfortably rooted in architecture and design (rather than in the rich experiences, processes and evolution of cities). 46

Jianguo Wu’s paper “Ecological Resilience as a Foundation for Urban Design and Sustainability” references Van der Ryn’s book Ecological Design where he describes urban design as disconnected from nature:

In many ways, the environmental crisis is a design crisis. It is a consequence of how things are made, buildings are constructed, and landscapes are used. Design manifests culture, and culture rests firmly on the foundation of what we believe to be true about the world. Our forms of agriculture, architecture, engineering, and industry are derived from design epistemologies incompatible with nature’s own. It is clear that we have not given design a rich enough context.47

Humanist critiques of urban design such as Inam’s that call for greater emphasis on social issues, and ecologically-based critiques such as Van der Ryn’s and Wu’s which argue for a more deliberate foregrounding of nature in the design of cities are, in their own right, important critiques. But when taken together they expose the inability for urban design, as it is currently understood and practiced, to effectively take on many of the complex and overlapping challenges of urban resilience discussed by other disciplines. They also signal the need for a new approach to the way we spatially code our cities; one that supports coexistence, synchronicity, and the transformative potential of both humans and nature.

Designing for resilience within a plurality of systems transcends the expertise of any one discipline. While C.S. Holling’s research is cited as the origin of contemporary resilience theory, it was developed by observing communities of insects.48 Urban communities are made up of far more complex social, economic, political, cultural, and spatial ecosystems; and when the impacts of natural hazards involve humans (as they do in cities), the metrics for success expand beyond basic survival to include issues of equity, opportunity, and general well-being.49 Recent advancements in resilience planning (also known as adaptation planning), promise a greater intersectionality of systems by combining hazard identification, asset mapping, vulnerability assessment, goal setting, scenario modeling, implementation, and monitoring. This involves a range of strategies including protection (engineered infrastructure that protects already built-up areas), accommodation (project by project modifications of existing buildings and other assets to accommodate occasional flooding in already built-up areas), avoidance (restricting new development in potentially vulnerable areas), and retreat (moving human and built resources out of potentially vulnerable areas). But while resilience planning theoretically balances consideration for ecological, socio-economic, and morphological vulnerabilities, in practice many so-called “resilience planning” efforts in informal contexts more commonly resort to a combination of protection through highly engineered solutions and retreat by mandatory resettlement.

Exploring the intersectionality of urban resilience and urban design presents an opportunity to intellectually and operationally advance both; extending the concept of urban resilience from one of observation to one of action, and expanding the disciplinary domain of urban design from one based in architecture to one that balances considerations for ecological, sociological, and morphological systems. For cities like Muntinlupa, at the crossroads of hyper-urbanization, informality, and climate change, designing with nature, not against it; breaking down development silos; and supporting socio-economic integration for growing and increasingly vulnerable urban populations can reduce vulnerability, increase resilience, and ultimately result in new and exciting forms of urbanity.

Appendix A: Summary of interviews with informal dwellers on lakeshore flooding.

Eric and Anican

Quote

“As a boy, I used to wade knee deep in the water to collect shellfish to sell.

The water level in Laguna de Bay is much higher today.”

Interview Highlights

Eric is a cellphone technician originally from Sucat. His father was a fisherman.

He remembers when the landscape in the area was completely different, with far less pollution. Eric’s son, Anican, attends a private school in Cupang and likes to spend time with his friends and family in the Sucat People’s Park.

Tiangco

Quote

“When I was a kid, the water was so clean; I could drink it and collect mussels

and snails.”

Interview Highlights

“When I was a kid, the water was so clean: I could drink it, and collect mussels and snails. We used to do more subsistence fishing and watercress farming, but there are now fish pens everywhere. However, the watercress still grows. Now, I’m a traffic enforcer; I work the night shift at the airport. It’s a one hour journey by two jeepneys, but I can’t move because my councilor nephew got me this job. Plus, it’s only 20 minutes usually, there is just construction traffic right now. When it floods, we all go to the school for refuge. The last time, it took four months to subside. I would like to move to the Baguio highlands, not just because of the flood, but because there is less traffic and it is cleaner and calmer.”

Carlos

Quote

“The flooding came all of a sudden, but didn’t subside for six months.”

Interview Highlights

Carlos works along Laguna de Bay. He is a fisherman, and spends his days catching fish and repairing watches to make ends meet. His livelihood and shelter is extremely vulnerable to flooding. His home is made of weak materials that could easily be swept away. He does not see many other options to survive in the city, and looks forward to a day when he will be able to earn more and be less vulnerable to rising waters.

Ferdinand

Quote

“When it floods, I move to the second floor of my house. Sometimes, it can be months before the water completely subsides.”

Interview Highlights

Ferdinand is a tricycle driver. In between rides, he rests at the main tricycle hub in Muntinlupa, which is located near the railroad track between Don Juan Bayview subdivision and Dona Rosario Bayview subdivision.

Trinidad

Quote

“To prevent flooding during the next storm, I believe that the government should be more strict when it comes to trash disposal and collection.”

Interview Highlights

“My friends and I all work as street-sweepers employed by the local government. We all have several children at home, and some of us are single mothers. I (Trinidad) live nearby in Cupang, but some of us come from further away: Bonoy Avenue in Manila, Luzon, four miles from here. Although we live in different neighborhoods, we’ve all been impacted by the flooding. For me, the effects were not too bad, just one or two feet of flooding that subsided quickly. To prevent flooding during the next storm, I believe that the government should be more strict when it comes to trash disposal and collection. Clogged canals cause and worsen the flooding. Although it floods, I’m not interested in moving. I’m satisfied with what I’m earning, and really just grateful to have a job, one that I stick with because of the wages. I’d even work further away, if it meant a higher wage.”

Concepcion

Quote

“We are used to flooding, but I worry about my family’s health when the waters don’t go down.”

Interview Highlights

Concepcion and her family have been fortunate enough to upgrade their house from bamboo and wood to cinder block. Their home is only a few meters from the water and is susceptible to flooding. With their material upgrades, they do not have to worry about damages as much some of their neighbors. They work outside of their community and have planned for their future to be able to invest in their child’s education and their family’s health.

Renato

Quote

“Because we live on higher ground, our home is usually not affected by flooding. What we really need is a safe place for our children to play.”

Interview Highlights

Renato has lived along the railroad tracks in Buli for 20 years. This area is located on higher ground and is generally not affected by flooding. Instead, Renato is concerned about the safety of the children who play along the rail line. He hopes for more public space in the future so the neighborhood kids can have a safe place to play. Renato works as a luggage porter at the Airport. He has a one-hour commute.

Alejandro

Quote

“In the end, I believe that this place can be cleaned up.”

Interview Highlights

“I was born in Bikol, son of an American father, but have lived here in Cupang for 31 years. I’m the father to 6 children. The youngest is 23 and works at a Jollibee at the fringe of the city, and the eldest is 36 and lives at home. Typically, I work as a bookbinder in the Muntinlupa City Hall, but I have work off today because of the Pope’s visit. On days like this, I go fishing with my friends for tilapia and milkfish. I live nearby, at the border of Alabang and Cupang. During times of flooding (like 2009, when flooding was bad and didn’t subside for 5 months), I go to my brother’s house, who lives nearby but in a higher place. Because I work in government, my income isn’t affected by the storms and I’m satisfied with the work that I am doing. To get to work, I take one trike and one jeepney, for around 30 minutes. Because I know the people here, I wouldn’t move, even for a better paying job. Many of my neighbors have moved since the last storm, though, including a friend who moved to the province, only to be hit by Hurricane Yolanda. In the end, I believe that this place can be cleaned up, and that it’s the responsibility of the MMDA to do so.”

Marikor

Quote

“During storms, the water can come up as high as I am pointing, so our family raised our house to slightly above this height.”

Interview Highlights

Marikor is unemployed and has lived next to the Alabang river for four years with her husband and young daughter. She is originally from Quezon Province, six hours to the south. She and her family could not find work there, so they moved to Manila for better paying jobs. She worked at an airbag manufacturing company in Santa Rosa Laguna (30 minutes away) until recently, when she ended her contract because it paid provincial wages. She knew that she could access better pay elsewhere. At her previous job, a free shuttle would pick her up and drive her to work. Her husband works in Pasay City (one hour away). He does not make much, but they are able to make ends meet. Their daughter is not in school yet, so she stays at home with her grandmother. Between floods, the family stores its belongings under the house. Unfortunately, because of their home’s location, there is rarely enough time to purchase food and water in preparation for storms. Despite flooding, Marikor’s family wants to stay where they are, because they are close with their neighbors. Since water flows toward the lake, homes upstream from Marikor are not affected.

Susan

Quote

“The people here are hard-working and down to earth. We live very simple lives.”

Interview Highlights

Susan worked for many years as an administrative officer for Muntinlupa City. She is now retired. One of Susan’s concerns is the new C-6, a dike highway that the National Government plans to construct in Laguna de Bay, several hundred meters off the coast of Muntinlupa. Susan worries that there will not be enough room for fish pens if too much land is reclaimed. She tells us that local fishermen are already struggling to make ends meet. The government currently assists the community by restocking fish twice a year and controlling invasive species such as the Knife fish.

Asunción

Quote

“We will always find ways to cope.”

Interview Highlights

Asunción works as a clerk issuing business permits for Barangay Buli. Asunción’s family has lived in the same compound in Muntinlupa for five generations; the family constructs a new house following each marriage. Though Asunción does not travel far for work, all of her children attended universities in Manila City - a commute of around one hour. Distance is not an issue when it comes to education. Unless there is an evacuation order, her family simply stays on the second floor of their home during floods. The worst flooding she can remember occurred in 2009 during Typhoon Ondoy. She reports that the water took nearly two months to fully subside.

Appendix B: Summary of interviews with informal dwellers on livelihoods and community.

Melvin

Quote

“This neighborhood is everything to me. My friends and extended family all live nearby.”

Interview Highlights

Melvin works as a tricycle driver in Alabang. He walks a mere 20 meters to get to his vehicle and takes passengers around Muntinlupa from dusk to dawn. He lives and works in this area because this is what he knows. He was born a few blocks away and depends upon his family and friends for help if there is a flood.

Adelina

Quote

“My husband’s livelihood is along the railroad tracks. After we were relocated we had to come back –this is his work.”

Interview Highlights

Adelina is an Informal settler who lives in a narrow space at the edge of the Philippines National Railways track. Her husband runs a railroad cart for a living. They returned to the area after being relocated several years ago. Given the opportunity, she wants a better life for her family.

Mark Antony

Quote

“I drive a rail trolley because there is no cheap, direct transportation through our community. But, when it floods, everything stops and I have no way to make money.”

Interview Highlights

Necessity sometimes leads to innovation. Mark Antony pushes a homemade rail car between heavily populated areas along the railway in Muntinlupa. His mode of transportation works only in the window between trains but provides an important mode of transportation for pedestrians who need a more direct route to their destination.

Fey

Quote

“Even though our home is safe, when flooding happens we lose our source of income since we can’t work.”

Interview Highlights

Fey moved to Buli when she was 19. She and her husband used to live in a self-built house, but they have since upgraded to a formal, three-story home. This house is raised and rarely floods. When it does, it is because waters drain down from the highlands. For this reason, Fey largely experiences flooding as a financial loss. She and her husband run two businesses (an Internet café and school bus company), both of which they are unable to operate during storms.

Lucy

Quote

“Flooding is not bad here - no more than a foot, so we have never had to evacuate. In fact, everyone comes here to eat during typhoons.”

Interview Highlights

“I was born here; this carinderia is in my mother’s house. My husband was a policeman, but he is retired now.

Our four children are all married - the oldest is 40 - but they still live here. The Geremillos are one of the oldest family names in Cupang. This barangay used to not be so busy, but it is crowded and chaotic now. Flooding is not bad in here, no more than a foot, so we have never had to evacuate. In fact, everyone seeks refuge in the school across the street, and we sell them food. Flooding is much worse near the bridge, but it only floods every seven years.”

Susan

Quote

“After the floods of Typhoon Ondoy, we decided as a community to rebuild our houses higher.”

Interview Highlights

Susan has served as the President of the Sucat’s Sitio Playa informal settlement for the last seven years. As President, she has lobbied for funds to convert some of the worn bamboo pathways into concrete near the roadside entrances of Sitio Playa. When new settlers attempt to build houses and join the community overnight, she is in charge of asking them to register with the Barangay Home Owners Association.

Jay

Quote

“I’m happy here. I don’t see any reason to get away.”

Interview Highlights

Jay has lived in Cupang his entire life. He values living close to his family and enjoys having multiple transportation options to his job at a law office, which is a 30-minute Jeepney ride away. During severe flooding, water in his home stays around a foot high for nearly a month. Jay and his family stay in their houses during this time and, despite the water, experiences only slight disruptions in water and electricity. Jay is not afraid of flooding.

Fhiemie

Quote

“I dropped out of college because I couldn’t afford the tuition. I am now working 14 hour days with the hope of going back to school soon.”

Interview Highlights

Fhiemie works in a small clothing shop in a Gillage near the highway. She travels for at least 30 minutes to and from work. She was a student a few months ago and is slowly adjusting to this new lifestyle. She is young and hopes for brighter opportunities to come.

Renato

Quote

“I was jobless in Quezon province. We moved here when my wife found a job in Muntinlupa. I stay home with the kids.”

Interview Highlights

Childcare, employment and hope for the future have created a unique situation for Renato and his family. With two children and a wife that works, Renato heads the household. He does laundry, takes care of a sick child, and makes sure his children have a brighter future.

Aileen

Quote

“We moved here because of the flood; it went up to our necks! Eventually I would like to move somewhere without flooding.”

Interview Highlights

Aileen is a sari-sari (convenience store) owner in Cupang.

Eddie

Quote

“Ten years ago, the tracks were filled with houses, but most were demolished. Mine was not, so I stayed.”

Interview Highlights

“I’ve lived along the railroad tracks for a long time, more than ten years. About ten years ago, the tracks were filled with houses, but most were demolished to make way for railroad improvements. My house was not, so I stayed. For day-to-day work, I drive a cart along the railroad tracks between Alabang and Cupang, taking people to market, to their homes, and to school. On off days, I rent the cart out to other drivers for a rate of 40 pesos; sometimes I’ll also take work in construction when it’s available. To eat, my family also grows bananas and cassava. The flooding isn’t terrible in my area; we’ve only really been impacted once, in 2009. Then, the flooding came up to our knees, but subsided after a few weeks.”

Appendix C: Summary of interviews with informal dwellers on flooding, livelihoods, and community.

George

Quote

“There used to be other families here, but they moved away because of the rising water. We decided to stay because we grew up fishing.”

Interview Highlights

When George moved to Cupang 42 years ago, he built his house next to a baseball field along the shores of Laguna de Bay. Back then, his family could drink the water. Today, George’s house is surrounded by water and is only accessible via boat or on foot along a series of precariously connected logs. George believes the water rose because nearby factories were constructed in the 1970s. George experiences flooding around three times per year. In the worst storm events, the 17 families that live in the area go to the local evacuation center. If flooding is minor, those who can’t swim retreat to land while George and other older fishermen stay, despite the fact that houses get washed away every few years.

Jocelyn

Quote

“I have no time for leisure. To make ends meet, I sell vegetables until 10:00 pm seven days a week.”

Interview Highlights

Jocelyn has lived in Buli since she was eight years old. To make ends meet, Jocelyn sells banana fritters in front of her house, her husband sells corn in Parañaque, and her father works as a fisherman. Jocelyn and her family live in a stilted house along the lakeshore. During flooding events, water levels rise up to eight feet. They evacuate once every two years due to flooding. Despite this, she does not want to move, as her family would lose their main source of income.

Virginia

Quote

“The neighbors help each other during floods by building temporary bridges to pass through to the main road.”

Interview Highlights

Virginia is a janitress in Makati. She prizes proximity to public transit, good schooling for her children, and having access to food. Virginia has lived in Sucat for 22 years. She lives in a two story concrete house in an informal community along the lakeshore of Laguna de Bay, where floods can trap her family on the second floor.

Resureccion

Quote

“Working in Manila allows us to send money home so that our two children can go to college.”

Interview Highlights

Resureccion moved to Muntinlupa so that she could earn income to help support her family. She and her husband send their extra money from fishing and construction to support their grandchildren’s education. They live a few meters from the water’s edge and do not expect to be able to stay in this location permanently because of the risk of severe flooding.

Myla

Quote

“I came to Manila so that my children could get a better education. It takes them 1 hour to commute to school each way.”

Interview Highlights

Myla came to Muntinlupa from the province of Samar and lives in the informal settlement of Daang Hari. In exchange for her son’s scholarship, she sweeps the church of Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal every Friday.

Marcello

Quote

“After each typhoon, new people move to Cupang, but they leave quickly for better areas that are closer to schools and major roads.”

Interview Highlights

“I was born here, am a retired well builder, and I own this lot and house. When it flooded last time, it went up four feet. We went to the evacuation center in the school, although we usually just repair the house and stay here. We make makeshift bridges to get from place to place, and before the flood we stock up on food and repair the house to prepare. I have no interest in moving, especially since I own this property and rent some units to neighbors. I would like to elevate the house though. When I worked, I made pumps and wells for groundwater. Groundwater is free, but it’s less popular now that the official water utility has come in. Fishing is not so popular anymore; my only relative here who fishes is my nephew After every typhoon, new people move to Cupang, but generally they leave quickly for better areas that are closer to schools and major roads.”

Jhary Ann

Quote

“I’ve only experienced flooding once. I’m not afraid of floods because I live on the third floor.”

Interview Highlights

Jhary Ann moved from Novatas to Cupang in 2007 to live with her husband. Here, she primarily works as a public school teacher. Since moving to Cupang, her family has only needed to evacuate once due to flooding. Jhary feels extremely safe, especially because her bedroom is on the third floor.

Jonnel

Quote

“I prefer living in a gated community because I think it is safer there.”

Interview Highlights

Jonnel has been a security Guard at the Church of Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal for one year. Originally from a rural province, he today lives in a barracks in the gated Posadas Village.

Ronalyn

Quote

“I like that everything in the barangay is within walking distance.”

Interview Highlights

Ronalyn is a high school student who works at her

cousin’s roadside snack stand on Manuel Quezon road.

Jason

Quote

“With climate change, this place is going to be like waterworld.”

Interview Highlights

Jason is an IT Engineer who runs a local bike shop out of his own garage. He lives in the Don Juan subdivision of Sucat. He has lived in the area for his entire life. Jason values the convenience of Muntinlupa, which, he says, is easily accessible by rail and by bike, as well as close to the airport. He fears the consequences of climate change and the relative lack of concern that many area residents have expressed towards its dangers.

Vic

Quote

“In my neighborhood, people are open, know each other, and interact on a daily basis. We are not divided by walls like in the gated subdivisions.”

“The main livelihoods in Sucat in the past were farming in the rice fields and fishing in the lake.”

Interview Highlights

Vic is the Barangay administrator of Sucat. He is a retired electrical engineer who values the community resources in the area.

Hilda

Quote

“I have no time for leisure. To make ends meet, I sell vegetables until 10:00 pm seven days a week.”

Interview Highlights

Hilda’s livelihood relies upon vibrant street life to sell her produce. She benefits from streetlights to sell vegetables later than most grocery stores would be open. She rarely has time for leisure activities and works from 7:00 AM to 10:00 PM at night, with only a short afternoon siesta.

Eduardo

Quote

“Since I moved here in 1998, the number of people living here has tripled.”

Interview Highlights

Eduardo’s occupation is flexible and adaptable. He sells food from bins and can modify his route should a flooding event occur. He came from his rural community to the city over 15 years ago looking for better prospects. He has made a stable life for himself in Muntinlupa.

Theresa and Carlito

Quote

“We’re retired and watch after this property for the land owners.”

Interview Highlights

Although not landowners themselves, Theresa and Carlito have built trust with the landowner over time and built a life for themselves and their family. In exchange for looking after a few hectares of land near the railway in Muntinlupa, they secured reduced rent and have been able to save money. They are both retired and receive a pension from the government. As a result, they have been able to invest in income-generating activities and raise chickens, perform basic mechanic repairs, and sell produce.

Matthias Garschagen et al., World Risk Report 2016 (Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft and UNU-EHS, 2016), http://collections.unu.edu/view/UNU:5763.

Makiko Watanabe and The World Bank, “Closing the Gap in Affordable Housing in The Philippines,” Policy Paper for the National Summit on Housing and Urban Development. (Manila, Philippines, July 2016), http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/547171468059364837/Closing-the....

Arnel Casanova, “Designing Bonifacio Global City” (Cities by Design II Seminar, Harvard University Graduate School Design, April 21, 2016).

Congress of the Philippines, “Climate Change Act of 2009,” Pub. L. No. Republic Act No. 9729 (2009), http://climate.gov.ph/images/documents/Republic_Act_No.9729.pdf.

“Typhoon2000.Com,” www.typhoon2000.com, November 1, 2013, 20.

Sim Van der Ryn and Stuart Cowan, Ecological Design (Washington DC: Island Press, 2007).

Niraj Verma, “Urban Design: An Incompletely Theorized Project,” in Companion to Urban Design, ed. Tridib Banerjee and Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, Routledge Companions (Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, UK; New York: Routledge, 2011); Alex Krieger, “Where and How Does Urban Design Happen?,” Harvard Design Magazine no. 24 (Spring-Summer 2006): 64–71; Joan Busquets and Felipe Correa, Cities X Lines : A New Lens for the Urbanistic Project = Ciudades X Formas : Una Nueva Mirada Hacia Proyecto Urbanistico (Rovereto, It.: Nicolodi Editore; Cambridge MA, USA: Harvard University, Graduate School of Design, 2006); “10th Urban Design Conference Proceedings,” Harvard University Archive, April 17, 1966.