Professor in Residence, Department of Architecture, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

As communities and design professionals confront complex cultural issues in planning, new tools are needed to introduce interdisciplinary cultural inquiry into urban design/planning. Reparative planning is premised on a reckoning with socio-economic and environmental decline through design of the built environment. Cultural mapping is necessary to both visibilize suppressed narratives behind decline and inequity, as well as underwrite new policy and development approaches. City in the Woods is a cultural mapping project that supports planning for Cherokee Village. Moving beyond the map as object to mapping as a process, we employed the deep map to sketch a memoir of place different from the disciplinary linearity found in conventional cartography. Cultural mapping animates diverse data sets through various visual literacies ranging from serial filmstrip narratives, to collages, thick description drawings that reconstruct lost local heritage landscapes, and geospatial mapping of the built environment. Change requires storytelling. This descriptive agency in planning, entailing collaboration between design professionals and community, models an equity-based approach beginning with stories that enable community self-advocacy, motivate institutional redesign, and construct new urban forms.

“The idea of development stands like a ruin

in the intellectual landscape.”

(Wolfgang Sachs) 1

Urban designers rarely get the opportunity to stage a deep dive into the cultural forces shaping a place before preparing plans. Contemporary planning in the US has been captured by a totalizing market logic, where home and public space have been financialized to serve investment interests. Since the 1930s when cities solidified their role as modern services providers with sole control over their land uses, planning has conformed to regulatory development templates designed to ensure growth rather than good placemaking. American cities, as urban historian Eric Monkkonen reminds us, are public corporations that came to see themselves as “economic (not social) centers” 2 for capturing growth.

Arguably, their overcommitment to debt financing, liquidity in property exchange, marketing, and capital formation eclipse old concerns for the social. Their planning regimes leave little room for important minor histories related to informality, indigeneity, vernacularity, working class solidarity, and other traditions structured around cooperation. These traditions constitute the pluriverse or the world conceived through multiple economic and social narratives. As planners understand, the contemporary city has become a stubborn socio-technical system resistant to change in its capital-oriented mindset. But what is to be done when the planning goal is reparative? How do we restore social, economic, and environmental functioning for the many populations left behind by our neoliberal economy? One first step is to revisit once-orienting cultural capital and voices lost to appropriation by settler mentalities motivated by financialization. Cultural mapping aims to improve models of interdisciplinary cultural inquiry in urban design and planning – a prerequisite to reparative planning.

EMBEDDING CULTURAL INQUIRY INTO URBAN DESIGN AND PLANNING

Modern cities are places of continual erasure, hastened by ever shortening cycles of the “creative destruction” theorized by economist Joseph Schumpeter. The enthusiasm for recovering a sense of place through invocation of plural land traditions, forgotten origin stories, and nonexploitative relations to the environment has elevated cultural landscape studies in land-use planning. Cultural landscapes are places of a recognized relationship among space, natural resources, and human activity, according to the Cultural Landscape Foundation.3 The University of Arkansas Community Design Center (UACDC) in partnership with Cherokee Village stakeholders – residents, community organizations, artists, folklorists, and historians – were given the opportunity to excavate an archeology of forgotten forces tangled up in the shaping of a planned community built during the mid-1950s in Arkansas. Cultural mapping of Cherokee Village was guided by participatory forms of inquiry, research, and representation of its minor histories. Surprisingly, cultural mapping revealed a far more robust and fascinating web of underlying influences than is evident in Cherokee Village’s built environment. Recall of these tangible and ephemeral forces empowered the community to envision unexpected planning possibilities for stemming economic stagnation and high poverty rates experienced among current property owners. The utopian promise of Cherokee Village, portrayed in its marketing materials, was most fully experienced by its first generation of homeowners but did not persist among successive generations.

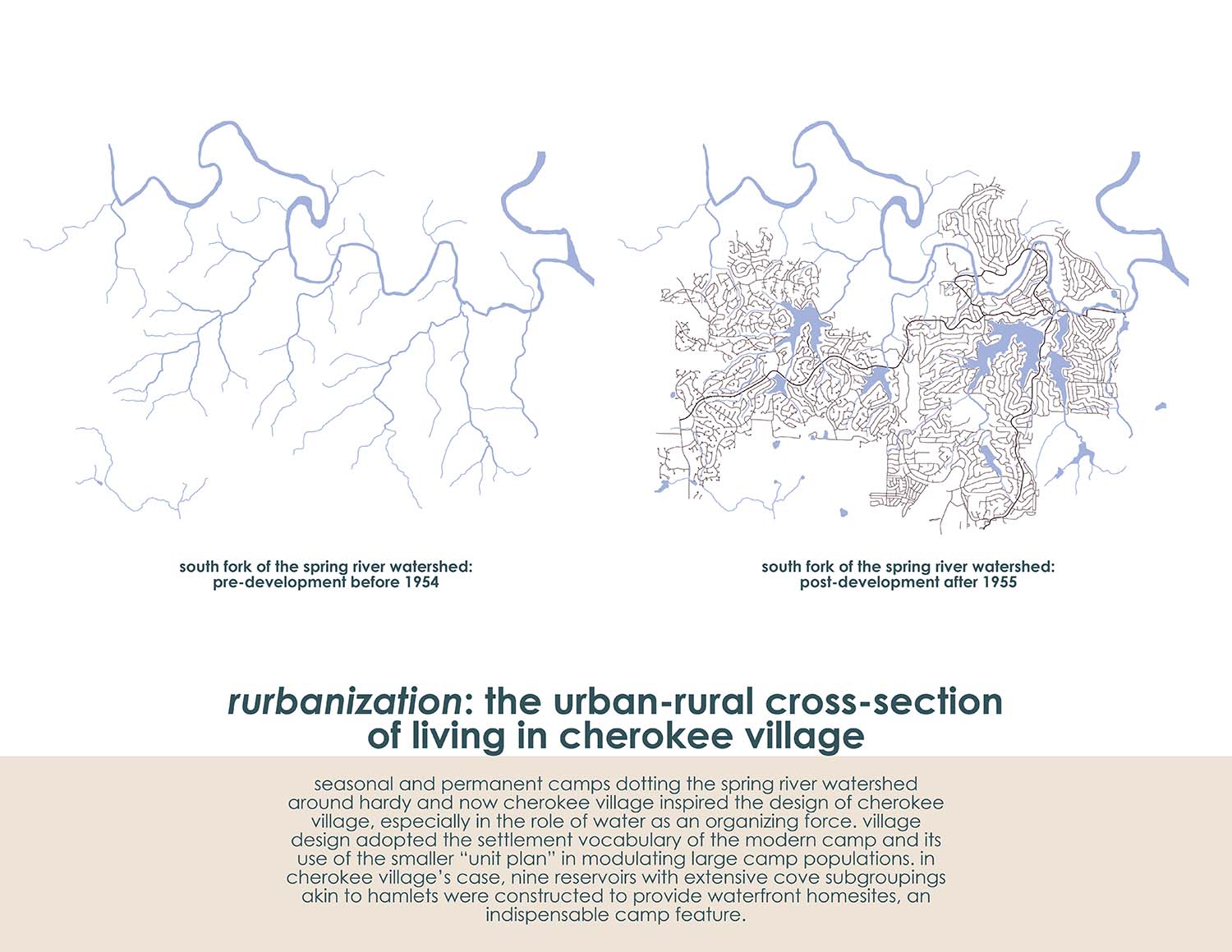

City in the Woods is a cultural mapping project that supports a subsequent Framework Plan commissioned by Cherokee Village and prepared by the UACDC to strategically develop the City’s 21.3 sq. mi [55 sq. km] area (population: 4,900). Cultural mapping describes the interconnectedness of landscapes, histories, and social geographies of the Arkansas Ozarks highlands surrounding one of America’s first planned retirement‐oriented recreational communities. The challenge is what does one do with a sprawling automobile-oriented community planned around arterial roads, cul-de-sacs, and single-family homes… where eighty percent of platted home sites remain vacant after more than sixty years… where 25,000 home sites were platted for a population of 60,000 serviced by 296 mi [476 km] of roads for access to only 3,100 houses…. where the median household income is $37,917 and 17.6% of the population lives below the poverty line despite the visions of modernity used to sell then award-winning Cherokee Village? 4

Like forty percent of US cities with at least 10,000 residents, Cherokee Village has experienced shrinkage, whether gauged by decline in population, employment, or economic development.5 Indeed, the inability to respond to the withering of US towns and cities remains one of the nation’s largest socio-economic challenges.

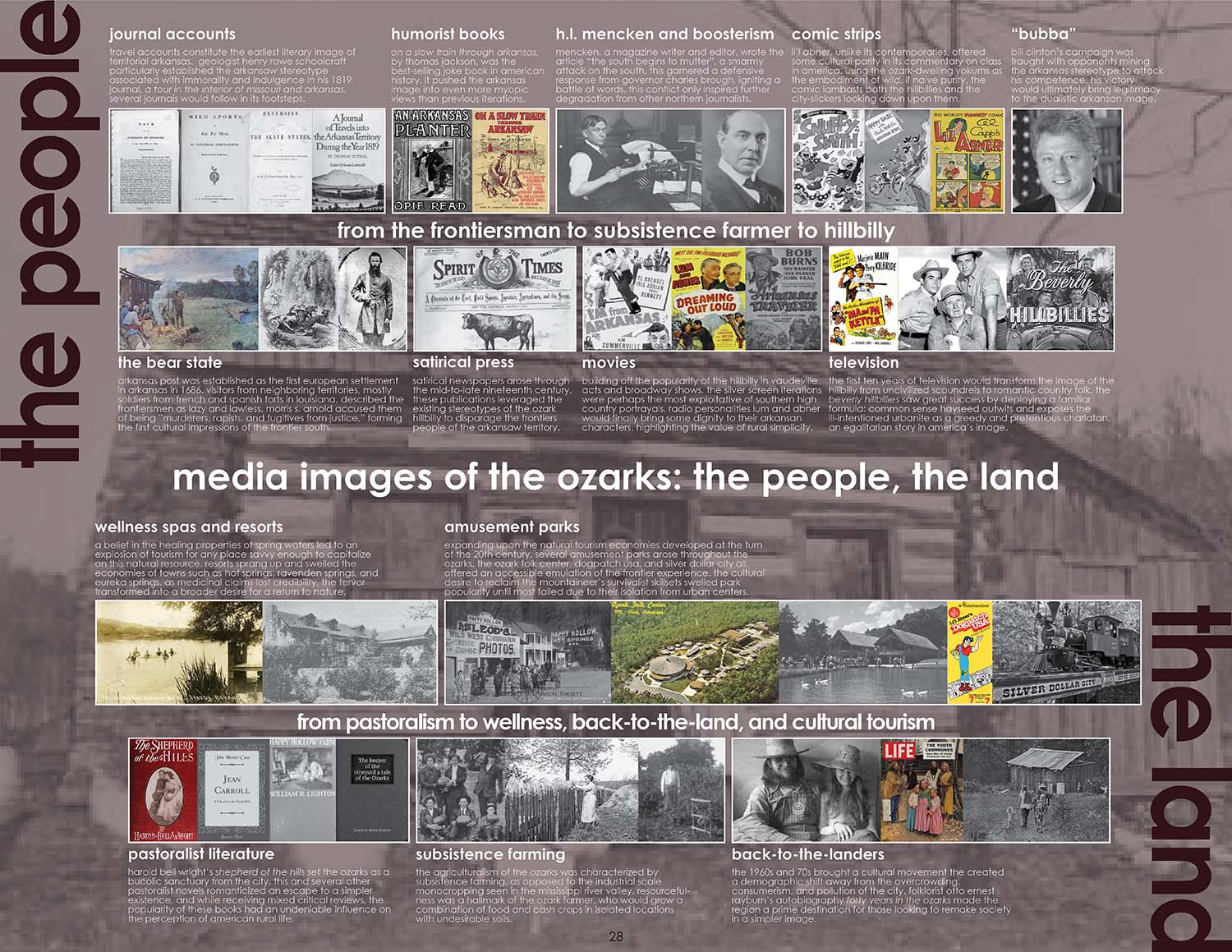

Cultural maps are not plans, site analyses, asset inventories, nor faithful descriptions of a territory. Rather, cultural mapping is a visual dialogue. Cultural mapping often recasts minor histories using folk, media, and archival resources to describe tangible and ephemeral systems across different eras in the interrogation of place. In this case, five cultural frameworks formulated by local arts and development leaders captured Cherokee Village’s originating story: Native American heritage, Ozark pioneer and folk heritage, camping and scouting, midcentury planned communities, and regional modernism in design and planning. Cultural mapping visibilizes the surprising constellation of land traditions employed in imagining Cherokee Village, though some frameworks overshadow others.

This critical cartography raises controversial public-interest issues including the appropriation of Native American identity and, ironically, the absence of social diversity among populations in planned communities. The novelty of Cherokee Village’s award-winning polycentric street network of arterials and cul-de-sacs pioneered in midcentury planning was countered by pre-modern imagery in Indigenous, camp meeting, and frontier traditions embraced by Cherokee Village’s developer John Cooper (Fig. 1). Cultural mapping resurrected a suppressed and far more complex development history smoothed over by time and the homogeneity of late modern planning. This unpacking of latent cultural-historical memory is a platform for envisioning new social and ecological planning possibilities otherwise implausible in conventional planning processes. Cultural mapping, thus, is epistemological in shaping how we see and know things.

The fifty-seven cultural maps reveal a fascinating story. Retirement community magnate Del Webb is credited with having created the retirement community industry based on his well-known development of Sun City, Arizona – an age-restricted retirement community opened in 1960. In her history of the post-WWII age-restricted retirement community, housing historian Judith Trolander celebrates Webb’s use of innovative market segmentation techniques, including subsidized mini-vacation packages and direct-mail marketing, in convincing seniors nationwide to relocate to his sunbelt leisure community.6 But John Cooper had already accomplished this six years earlier in 1954 when he opened Cherokee Village, a planned retirement-based recreational community in the Arkansas Ozarks. Cooper targeted both senior and young households (average property purchaser age was 47) 7 who would vacation in and eventually retire to this forest community.

Cooper did not employ age restrictions and even donated land for the construction of schools.8 According to Trolander, Del Webb and his management consultants reacted with skepticism to these new demographic segmentation techniques in marketing when they first learned of the retirement community concept through a 1957 NBC show featuring nearby Youngtown, Arizona. Youngtown, the first age-segregated retirement community was developed in 1954, the same year as Cherokee Village. However, Cherokee Village differed from both Youngtown and Sun City. The latter Arizona communities reflected a deliberate generic suburbanism to attract home buyers from all regions across the US. While all three progenitor planned communities were marketed around the trope of the vacation, Cooper’s vision was unique in combining influences from both modern and folk/regional development traditions. Cooper was particularly drawn to the long-established camp meeting tradition throughout the Ozarks with its emphasis on social pluralism and family in civilizing this highlands landscape (Fig. 2).

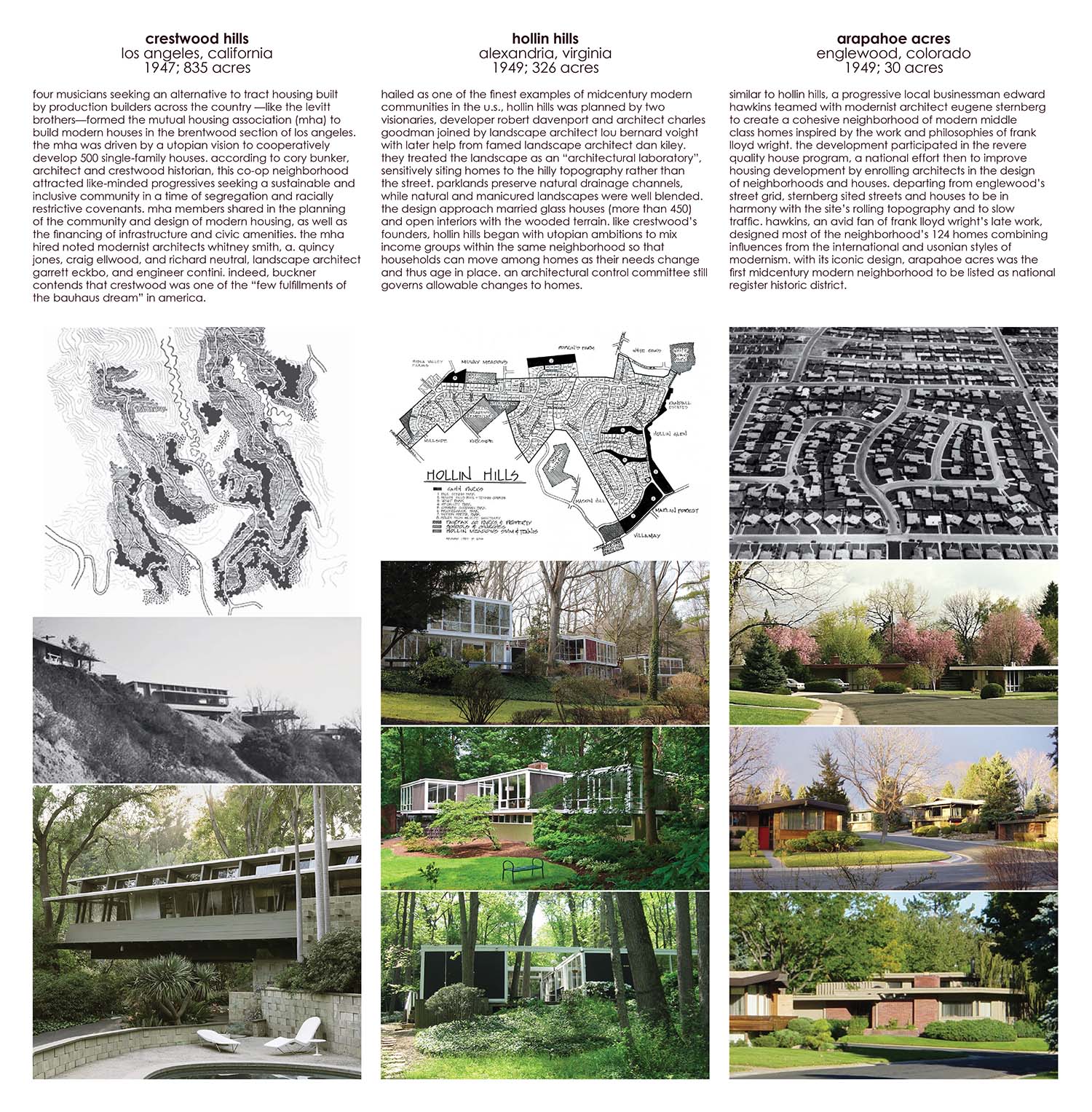

The significance of City in the Woods lies in its recall of divergent cultural trajectories engaged by Cooper to conceptualize a new settlement pattern: the planned community organized exclusively around the single-family lot and low-density development requiring automobile travel. Such post-WWII special-interest communities signaled capital’s shift from investment in the centralized infrastructure of the dense nineteenth-century industrial city of production, to suburban real estate development and its wraparound culture of consumptionand the marketing of land. Along with peer developments in America’s inaugural class of postwar planned communities (Fig. 3) – Levittown, New York being the most well-known – Cherokee Village was a real estate product unmoored from any placemaking precedents. Community developers like Cooper were essentially winging it, devising untested forms of financing, real estate marketing, rural building supply chains, and governance alternatives to the incorporated city. Most greenfield developers simply exercised a crude rationality by subdividing sites into parcels for improvement by merchant home builders. Cooper was the rare community builder who aimed to combine functionalist modern design with countercultural American regionalism rooted in organicist planning approaches for a highlands forest. An iconoclast, or at least as much as a developer with a lot of capital on the line could be, Cooper intellectually gravitated toward the pluriversal: the world as conceived through multiple economic and social narratives. Or to use the well-known Zapatistas phrase: “A world where many worlds fit.” 9 Cooper was searching for a social complexity organic to traditional communities.

Alas, the plural land traditions celebrated by Cooper were never reconciled with the unyielding economics of the midcentury automobile-oriented subdivision, singularly committed to the single-family home and its rigid social arrangement in the nuclear family. Nonetheless, Cherokee Village’s origin story offers a compelling repertoire of land traditions connected by their commitments to hospitalityas a planning episteme. Here, cultural mapping unearthed subaltern influences from camp meetings, revival grounds, healing resorts, scouting camps, and countercultural leisure and performance spaces as powerful but nearly forgotten proto-urban forms deployed to civilize the Ozark frontier. These urbanized forms of hospitality offer a viable urbanism (and livelihood) for renovating Cherokee Village’s calcified living environments. Hospitality is the ultimate social resource for reasons that will be examined in the form of a conclusion after review of the cultural mapping project.

CULTURAL MAPPING: CO-CREATED INQUIRY WITH COMMUNITY AND MEMORY

Moving beyond the map simply as object to mapping as a process, cultural mapping as defined by communications expert Nancy Duxbury “aims to make visible the ways that local cultural assets, stories, practices, relationships, memories, and rituals constitute places as meaningful locations, and thus can serve as a point of entry into theoretical debates about the nature of spatial knowledge and spatial representations.” 10 Cultural mapping is employed to sketch a memoir of place (what some call a deep map) different from the disciplinary linearity found in conventional cartography (though that too is used). Cultural mapping animates diverse data sets through representational strategies akin to a novel. Multi-modal drawings engage visual literacies ranging from serial filmstrip narratives, to collages, thick description drawings that reconstruct lost landscapes, and geospatial mapping of Cherokee Village’s built environment. Media environments were queried to map midcentury White perceptions of Indigenous and settler folk cultures (a mix of cultural appropriation, regard, supremacy, and caricature), key to understanding Cherokee Village’s origin story.

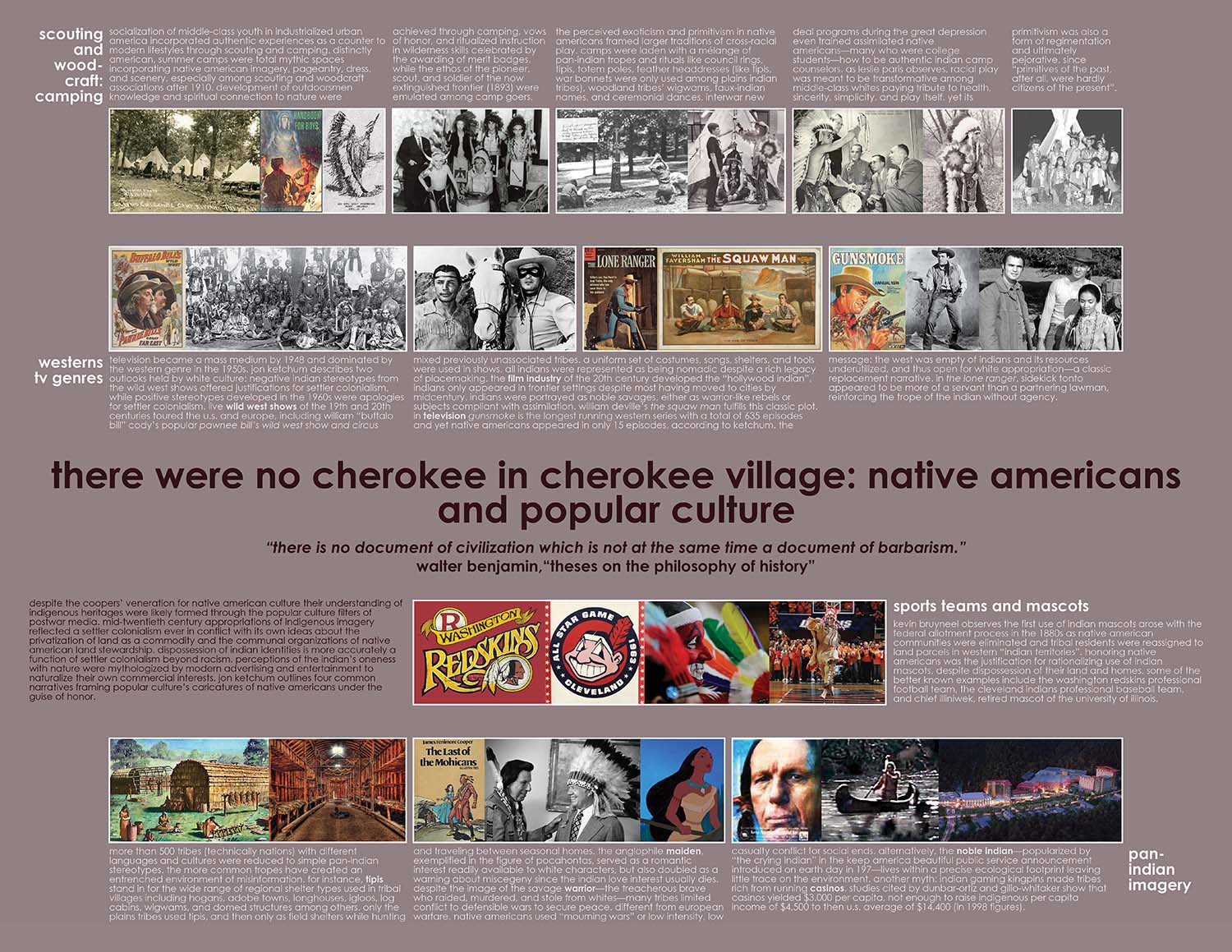

Here, mapping tracks the racial-reinforcing myths that influenced the development of a new social geography. What was the milieu in which Whites could believe that Native Americans had disappeared? Media theorist John Durham Peters argues that while media are commonly perceived as environments, too, environments themselves are media,historical constituents of habitats, material culture, and socio-political life in a place. That is, media is not just the message or the figure, but rather the ground – media is indeed infrastructural.11 Modern communities cannot be dissociated from the various media that shape them and the representations by which its subcultures are understood. (Fig. 4)

Following William Least Heat-Moon’s self-coined notion of thedeep map from his PrairyErth (a deep map)12to sketch a memoir of Chase County, Kansas, performance studies expert Mike Pearson and archaeologist Michael Shanks define the plural logics underwriting deep map constructions. Their notion of the deep map’s polyvocality is especially useful as a tool for making sense of Cooper’s own reach across cultural traditions.

Reflecting eighteenth century antiquarian approaches to place, which included history, folklore, natural history and hearsay, the deep map attempts to record and represent the grain and patina of place through juxtapositions and interpenetrations of the historical and the contemporary, the political and the poetic, the discursive and the sensual; the conflation of oral testimony, anthology, memoir, biography, natural history and everything you might ever want to say about a place.13

Likewise, City in the Woods as a cultural mapping project cuts across dominant histories (developer economics, middle-to-upper-class homeownership, and modernism) and minor mostly hidden histories (Native American ontologies, camping and youth scouting, and Ozark subsistence settler and folk culture) in imaging Cherokee Village. The map is no longer the smooth data-oriented product of professional cartographers because the deep map invites co-creation of cultural inquiry among community stakeholders, artists, and allied design professionals. Embedded knowledge among inside stakeholders is negotiated with the professional orientations of outside folklorists, historians, and design professionals who are more reliant on disciplinary models in conducting cultural-historical analyses. This inquiry was collaborative yet critical, entailing a three-pronged process of engagement, research, and advocacy. First, with technical assistance from the National Endowment for the Arts, community leaders in the arts and development constructed Cherokee Village’s story using the five cultural frameworks – Native American heritage, Ozark pioneer and folk heritage, camping and scouting, midcentury planned communities, and regional modernism. This story was essential in organizing further research by others, confirming Michel de Certeau’s important observation: “What the map cuts up, the story cuts across.” 14

Second, local stakeholders and design professionals researched oral histories, primary sources, archived folklore material, and published histories of Cherokee Village and area highlands culture accordant with the five cultural frameworks. Political theorist Clarissa Hayward observes that who we are as both individuals and collectives is a function of narrative construction. In her examination of the “narrative identity thesis,” Hayward asserts that: “Identification is unavoidably selective, exegetical, productive, and evaluative. Narrative as a discursive form captures and mirrors these qualities.” The narrative production of identity, especially its uncritical institutionalization and reproduction, as Hayward summarizes, may take the form of bad stories 15 (like playing Indian and other mythologizations of race and ethnicity) that warrant deconstruction and/or transformation into good stories. Cultural mapping is especially useful for communities aiming to examine detrimental social narratives difficult to decode once they are socially naturalized.

Third, from community-based research, design professionals constructed multimodal drawings, projecting cultural-historical narratives that tell multiple and sometimes divergent stories. Mapping iterations invited community feedback giving professionals direction in refining development of the five cultural frameworks. More than autonomous or fixed statements, deep maps are open exegetical tools generating inquiry (it was difficult to know when to stop) useful for later scenario planning. Professionals ventured into topics typically disassociated from planning and design, amplifying the public relevance of the otherwise rootless professional. Cultural mapping positions design professionals to be facilitators of larger cultural exchange beyond their role as simply creators of end‐of‐the‐pipe planning solutions.

Change requires storytelling. Cultural mapping provides new perspectives on blind spots in what seemed to have been promising development models at the time – that is, automobility, single-use zoning, lack of services, or the overemphasis on recreation as a social glue. City in the Woods curates multiple perspectives across two temporal frameworks: diachronicdevelopment – those evolutionary relationships which develop over time, and synchronicdevelopment – those relationships considered at one moment in time (like in conventional cartography). Such archaeological imagination is a productive tool for opening discussion around otherwise unconsidered planning possibilities, while cultivating greater collective awareness about Cherokee Village and its good and bad stories.

CITY IN THE WOODS: COOPER’S IMAGINARY AND OTHER POSSIBLE SOCIAL WORLDS

Every Twelve Seconds a Man Retires

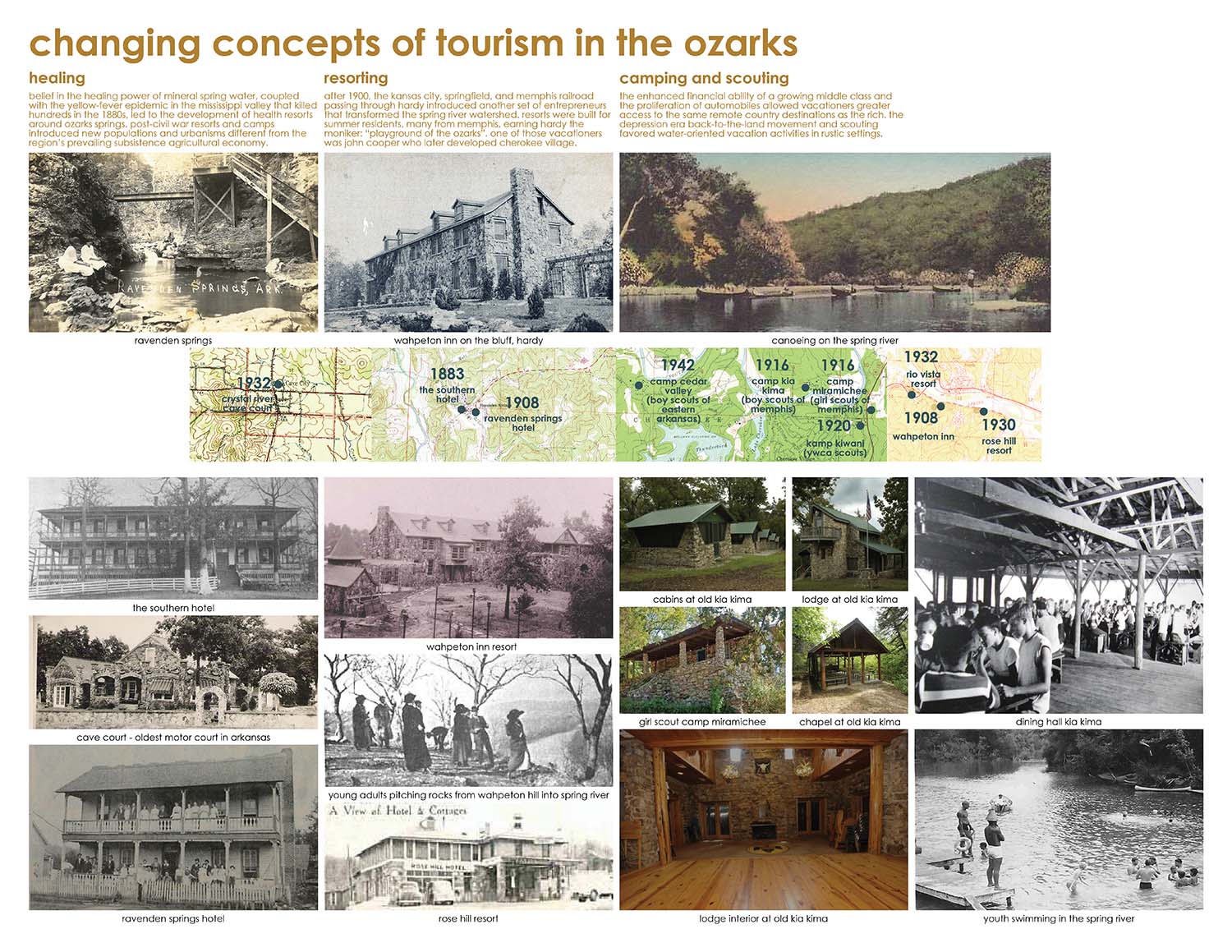

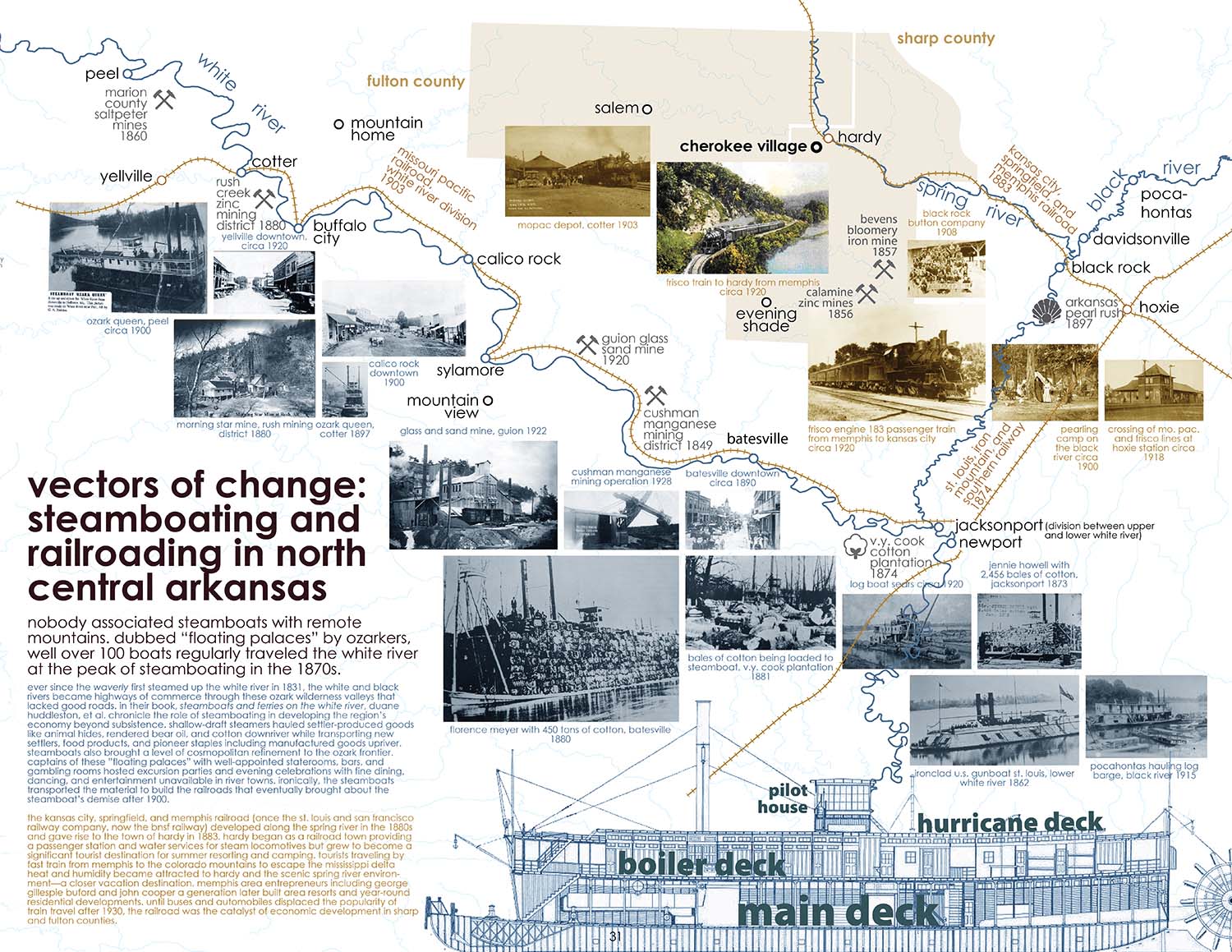

Born in Earle, Arkansas, John A. Cooper, Sr. (1906-1998), like other affluent vacationing Memphians since the turn of the twentieth century, sought resort in the Ozark highlands away from the summer heat and humidity of the Arkansas Delta on the Mississippi River. The town of Hardy was the first railroad stop in the Ozarks for those traveling west from Memphis to Denver and San Francisco. (Fig. 5) Before its railroad boom, Hardy – a Spring River town – had long been a popular camp and resort spot among Native American tribes (where the Osage and other Siouxan tribes held Olympic-style games),16 frontiersmen, settlers, vacationers, and later youth scouting troops from Memphis. Cooper, the vacationer-cum-developer since the 1940s, embraced the more radicalized experiences of Ozark culture and nature as he conceptualized a retirement-based recreational community on the nearby South Fork Spring River in the early 1950s.

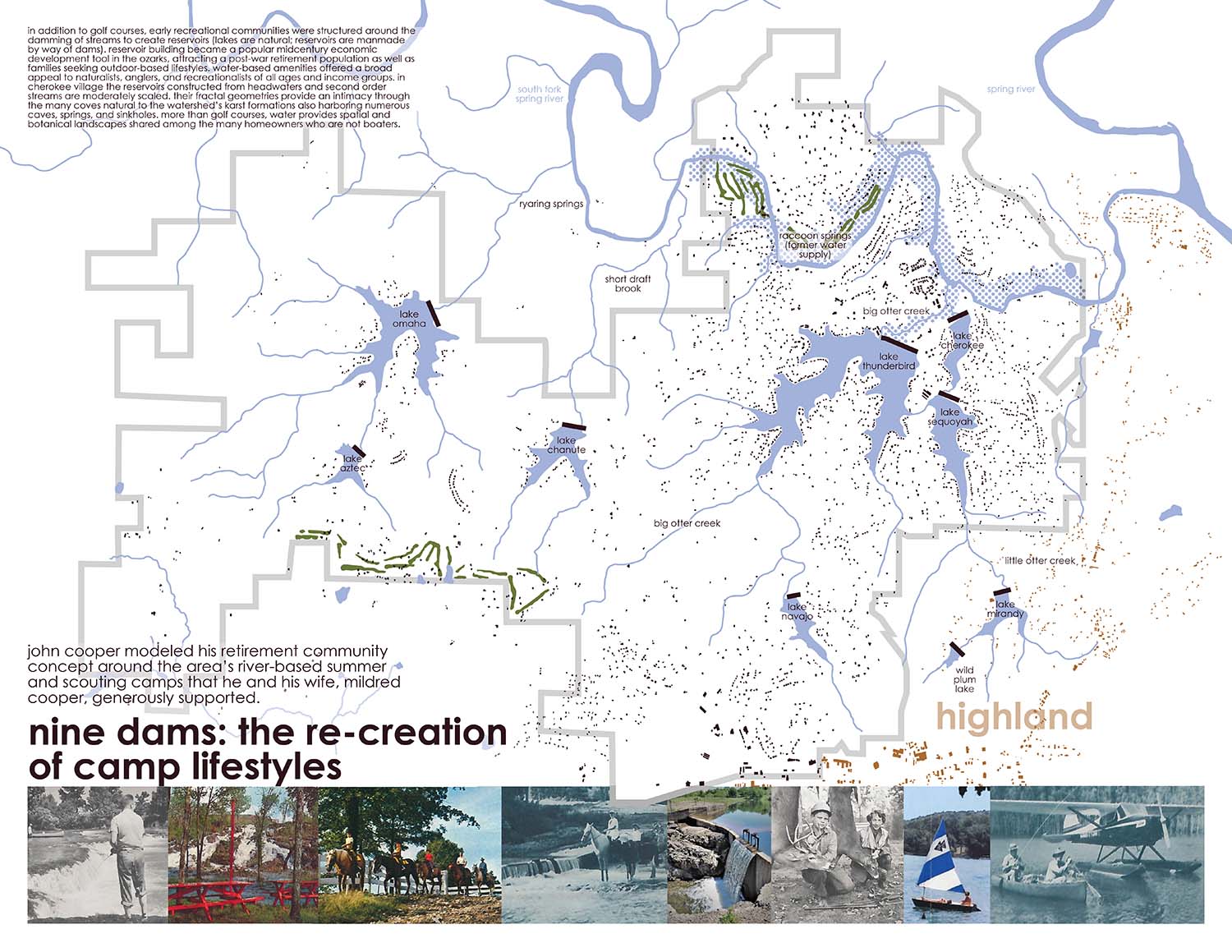

John Cooper recognized an emergent market opportunity in the new generation of retirees as postwar retirees were the first to enjoy full social security benefits, pensions, unprecedented mobility, extended life expectancy, and new notions of self-actualization. Cooper tapped into emergent sociological thinking that countered entrenched, often grim, conceptions of aging through the notion of active lifestyles. Cooper’s research fully grasped this scope of change, observing that “every twelve seconds a man would be retiring; every twelve seconds a man would be receiving a gold watch.” 17 Cherokee Village’s sales force – over 130 at its peak in the 1970s – was the first to deploy new marketing techniques including free vacation packages to tour home sites and direct-mail advertising. Within a 21 sq. mi [54.4 sq. km] area, Cooper dammed headwater streams creating seven lakes as nodes for organizing 25,000 home sites while preserving the area’s forest. This capital web of reservoirs and roads created a distributed order for selling home sites across the Village’s expansive territory. (Fig. 6)

Cherokee Village attracted thousands of property owners from all fifty states and twenty countries to this Ozark foothills community. Cooper’s encounters with Ozark land traditions are sampled below, while the entire cultural mapping project can be viewed at https://uacdc.s3.amazonaws.com/UACDC_Cherokee-Village-Cultural-Mapping.pdf.

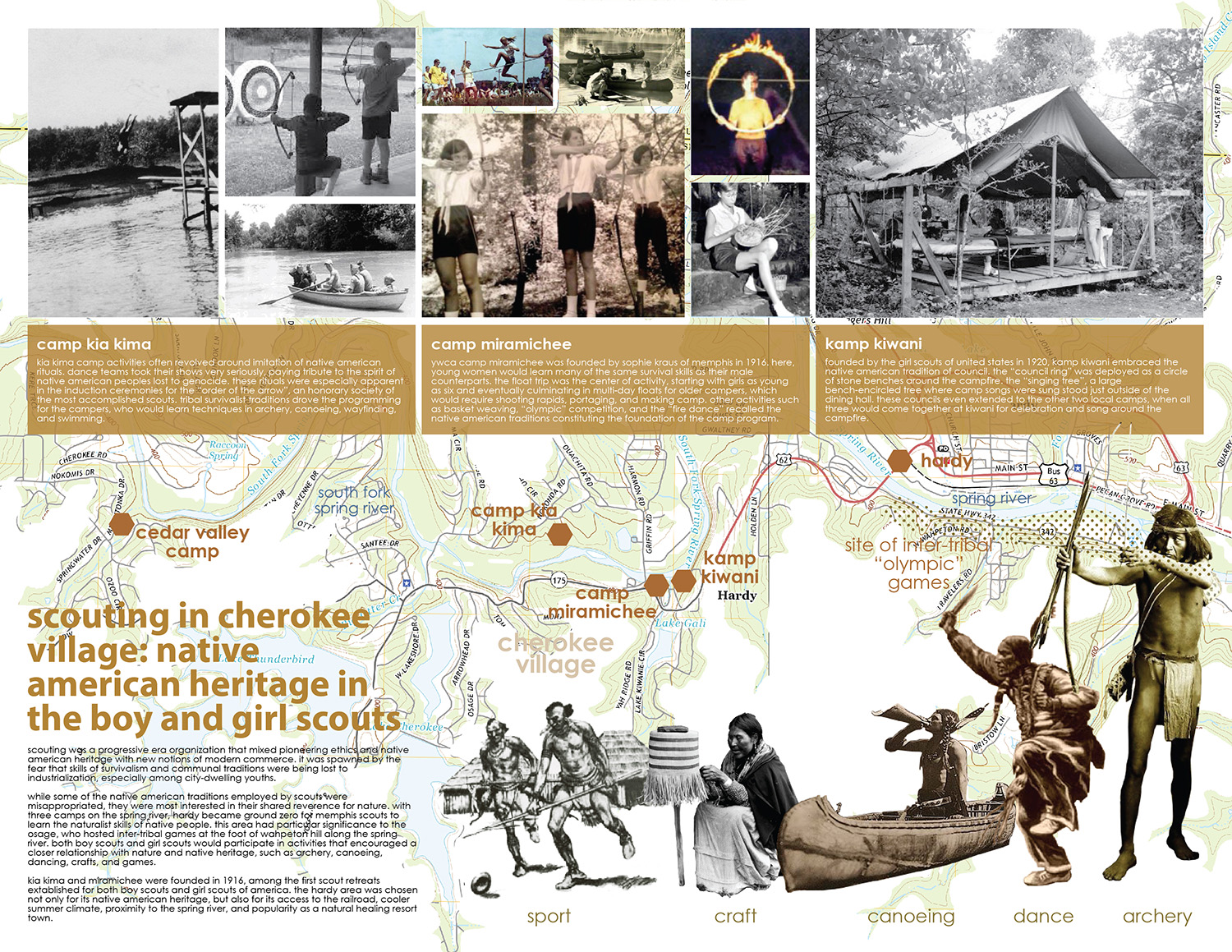

Native American Heritage: “Playing Indian”

John and wife Mildred Cooper venerated Native American culture; indeed, Indian sayings were engraved throughout their Cherokee Village home. Despite the Coopers’ veneration for Native American culture their understandings of Indigenous heritages were likely formed through the white-supremacist filters of postwar popular media. Cherokee Village was named in acknowledgement of an alleged Cherokee settlement nearby, while its Thunderbird and Omaha recreation centers, Sitting Bull club restaurant, and streets were given Indian names by the Coopers. Both Coopers were donors of time, land, and money to national scouting organizations that built significant camp facilities, most pre-dating Cherokee Village. Scouting drew heavily upon Native American tropes in a return to primitivism as an alternative education for urban youth. Postwar-era appropriation of Indian names and imagery extended a long and troubled relationship between Indians and White settler culture that displaced Indigenous peoples from their homelands.

As author Philip Deloria argues in PIaying Indian, Americans have indiscriminately appropriated Native American imagery and enacted racialized Indian roles throughout the nation’s history to shape White national identity. From colonial insurrectionists dressing up as Indians to carry out the 1773 Boston Tea Party, along with other carnivals and misrule rituals (e.g., the Whiskey Rebellion of 1791-1794, and the post-revolutionary war Tammany Societies), to the formation of nineteenth-century ethnographic studies around the ideology of the vanishing Indian (they are still here), conceptions of Indianness changed over time. Revolutionary-era Indianness celebrated self-determination, Americanness, and perceived freedoms in open landscapes. But what is clear to Deloria is that America ultimately “desired Indianness, not Indians.” 18

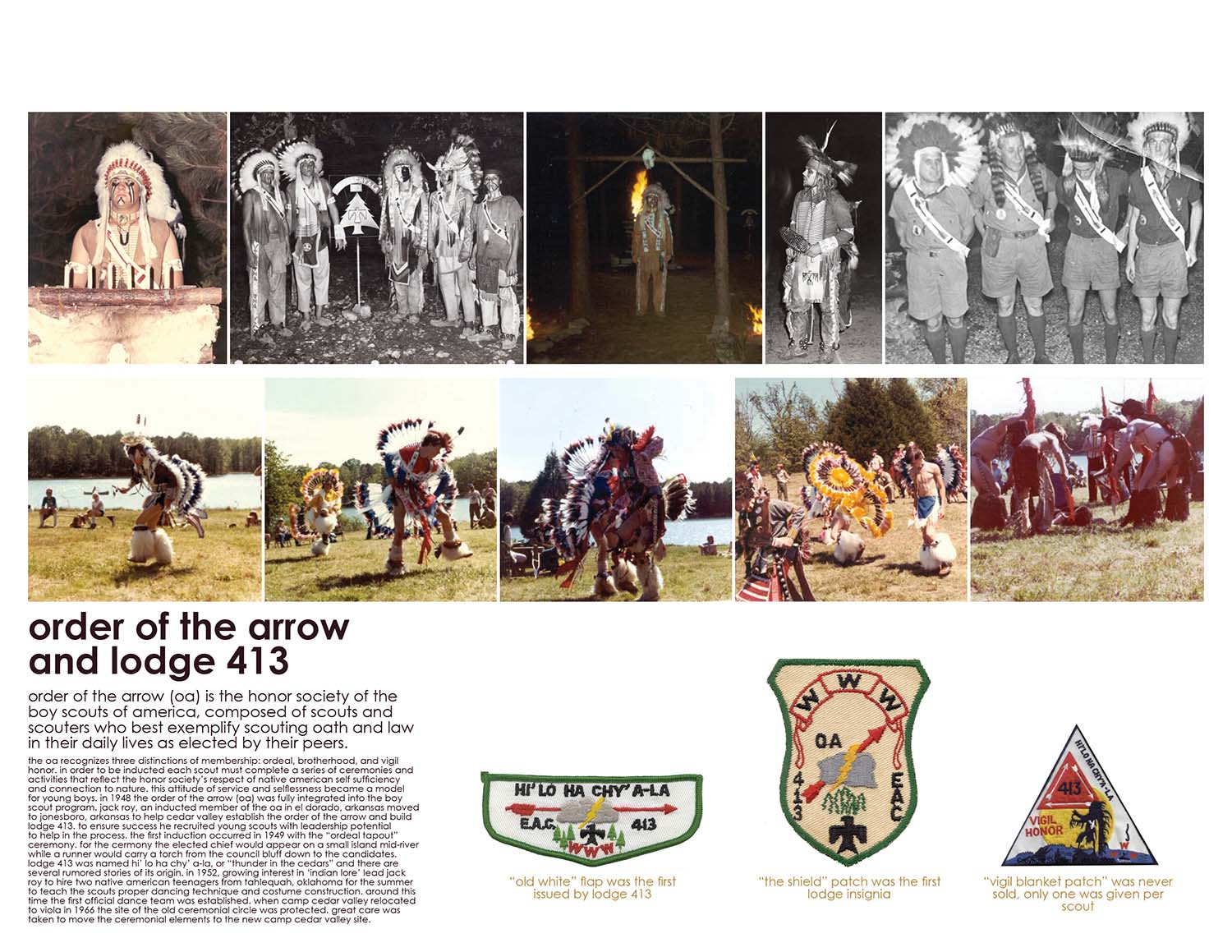

During the twentieth century invoking Indianness helped Americans confront anxieties over the environment, authenticity, the Cold War, and the dislocating effects of modernity. The scouting youth movements originating in the early twentieth century, including the Woodcraft Indians and Camp Fire Girls, were at the forefront of enacting Indianness to reestablish links to nature missing among urban youth in industrial society.19Interwar period summer camps codified Indianness through practices including dressing up as Native Americans, performing Indigenous dance rituals, and casting vows of honor around council rings among facsimiles of tipis, totem poles, and wigwams (Fig. 7). Conjuring an ahistorical all-knowing pan-Indian figure (the noble savage combining customs and skills from unassociated tribes), education in woodcraft – the art of living in the woods – was an organizing principle of the interwar summer camp. Woodcraft teaching was accompanied by a focus on the development of handicraft, agriculture, and social skills. Camps became important incubators of middle-class values, mixing instruction in thrift, adventure, reciprocity, and hospitality.

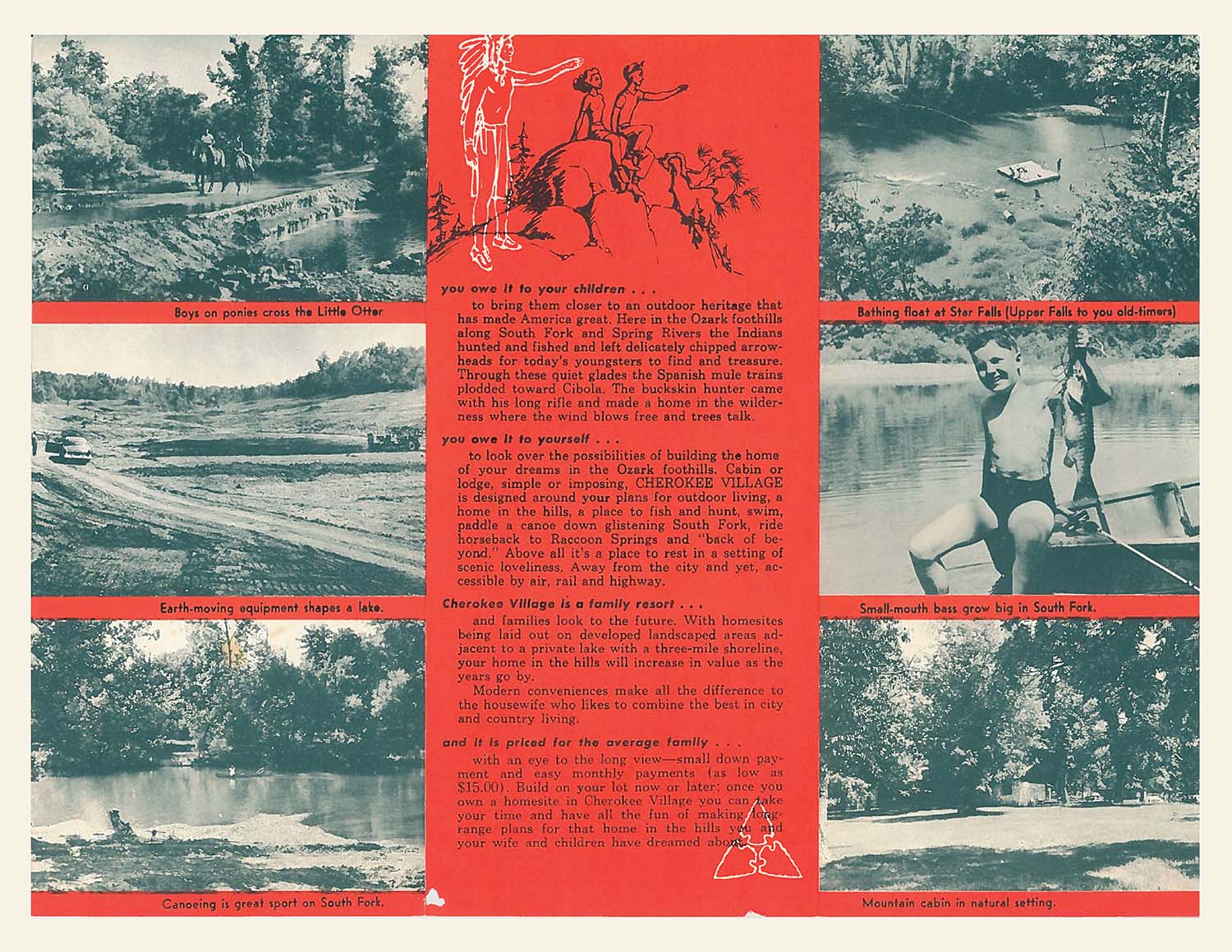

Indeed, Spring River basin camps and resorts – the area’s frontline for pioneering permanent settlements – thoroughly Indianized the resort and summer camp landscape after WWI. The idealization of a seemingly primitive, timeless, and purifying Native American ethnography provided a counter to modernization processes that were felt to be more alienating than liberating. Playing Indian was mixed with the era’s progressivist tendencies to seek redemption in nature, both underwriting the social reconstruction of modern childhood and national identity. The veneer of Indian lore and motifs deployed in camp life – what Leslie Paris calls “camp’s arcadian fantasies” while “sheltering children from the wilderness that they extolled” 20 – migrated to permanent developments like Cherokee Village. The White search for authenticity is a distinctly modern condition; a quest for this otheras Deloria argues that “can be coded in terms of time (nostalgia or archaism), place (the small town), or culture (Indianness).” 21

Like most economic and social relationships in America, even for non-Indians, these relationships oscillated between destruction and creativity, or “bad stories” as Cooper’s conflation of tribal cultures in a pan-Indian imaginary shows.22 Nonetheless, Deloria consistently shows that the social construction of Whiteness cannot be disassociated from the social construction of Indianness. Cooper’s association with the Cherokee was mythic, confirmed by Ozark historian Brooks Blevins who ironically observed: “There never were any Cherokee in Cherokee Village.” 23

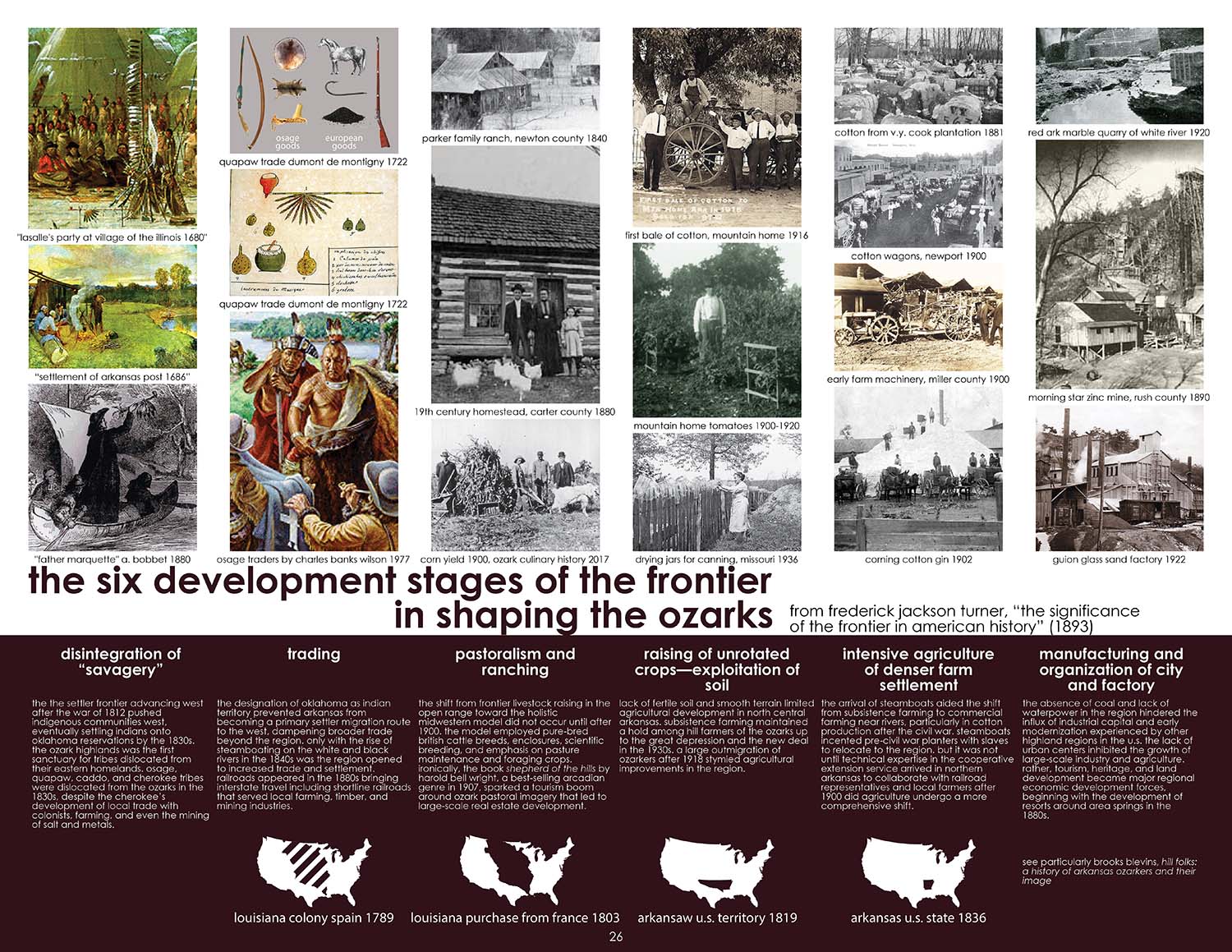

Ozark Pioneer and Folk: Arcadian Imagery – Tourism and Real Estate Transform the Ozarks

The designation of Oklahoma as Indian Territory directly to the west prevented Arkansas from becoming a settler migration route westward, atrophying its frontier development processes (Fig. 8) and creating what Blevins calls the “millpond effect.” 24 Only with the rise of steamboating on the White and Black rivers in the 1840s did the region open to increased trade and settlement. However, the absence of coal, and lack of waterpower, hindered the influx of large-scale industrial capital and early modernization experienced by other highland regions in the US.25 Despite the lack of urban centers in the Ozarks, nature tourism, heritage, and land development became major economic development forces, beginning with resort development around the area’s springs in the 1880s.

Middle-and-upper-class tourists and investors (the latter to extract timber and minerals) from Kansas City, St. Louis, and other cities north were attracted by pastoral imagery depicting the Ozarks. Arcadian imagery promoting classical, genteel visions of Ozark agrarian life – solidified by Harold Bell Wright’s 1907 national best-seller The Shepherd of the Hills – established a national basis for the region’s commercial tourism. Railroads overcame the geographical and cultural barriers stymieing urbanization of the Ozark’s rugged and remote frontier. Through cave parties, river float trips, game parks, and fish camps, regional boosters including railroad companies advertised the Ozarks as a continuous pastoral playground. The Ozark float trip staged by outfitters became memorialized in the region’s journalism and folklore as discussed by Morrow and Myers-Phinney in their history of tourism in the Ozarks, Shepherd of the Hills Country. Tourist-sportsman excursion venues evolved into resort cities as streams were dammed, which in turn brought a rush of homesteaders from across the nation to real estate developments after WWII.26 Besides its natural recreational assets, the region’s folk heritage – seen as hospitable and exotic – attracted back-to-landers looking to withdraw from urban lifestyles. By the end of the Great Depression, folk culture was being manufactured (Fig. 9) to attract tourists and new residents at the very moment native Ozarkers were emigrating to the American west and north due to their inability to make a living at home.27 Likewise, Cooper’s promotional brochures marketed a back-to-the-land rusticity, while community developers nationwide favored a benign aesthetic in appealing to a broad consumer market.

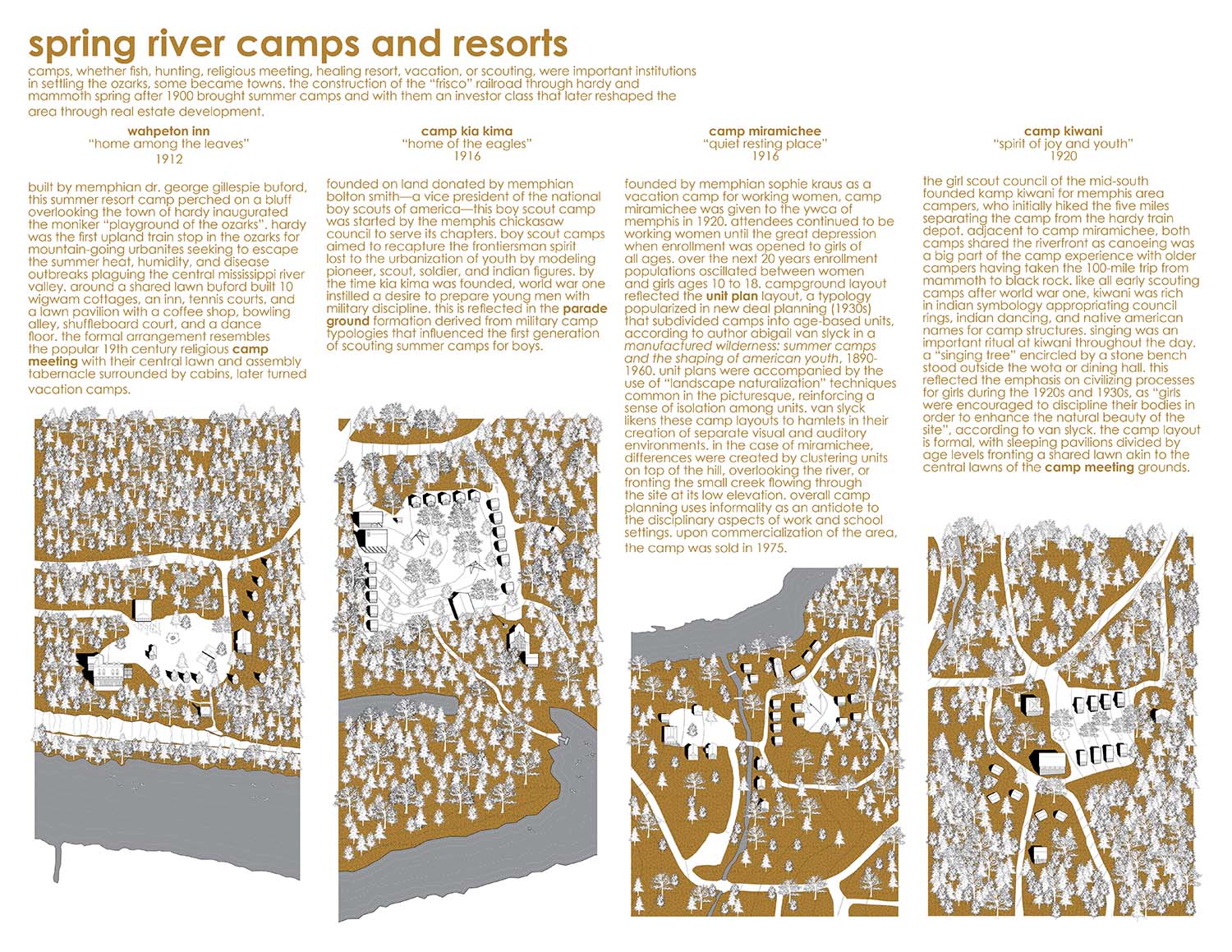

Camping and Scouting: The City in the Woods

“In manufacturing a new type of wilderness out of what – in many cases – had been farmland, summer camps (and to some extent, other rural resorts) seemed to turn back the clock, reversing the westward motion of the advancing frontier and returning the landscape to something that evoked its pristine natural form. Indian names suggested that the land had passed into the hands of camp organizers directly from its indigenous inhabitants, and thus worked conceptually to scrub the land clean of its earlier productive manifestations…” 28 Abigail A. Van Slyck

Construction of the long-haul Frisco railroad through Hardy in the 1880s fueled expansion in residential summer camps and resorts, attracting a new type of investor class that later reshaped the Spring River basin through real estate development. Cooper was drawn to the uniquely American institution of the camp meeting and its role in civilizing the Ozark frontier. Hunting, fishing, and healing camps based in pragmatism and cooperation shared the woods with transcendental religious and educational camps, both giving way to twentieth-century seasonal social resorts. In Camps: A Guide to 21st-Century Space, Charlie Hailey indexes the camp’s range of purpose, from subjugation to discovery and self-expression, through a variety of forms. At their best camps are generative cultural forces. Mythic and ritual-bound “spaces of play outside societal norms”, 29 camps enact important life transitions. “Combining field and event, camp is in effect spatial practice. Camp spaces also lie at the confluence of mental and social space… camp is both field of research and a kind of contemporary field research.” 30

Trolander recalls that camping and hoteling by “tin can tourists” wintering in trailer courts were accessible retirement strategies before the institutionalization of pensions and postwar retirement communities.31 The American camp meeting movement, popularizing community experiences in the woods, from religious revivals to cultural exchanges, became source material for a uniquely American form of settlement – the special interest community. Though the special interest community was rarely as interesting as its informal predecessors, it included recreational and retirement communities, resorts, bungalow courts, pocket neighborhoods, trailer parks, and utopian projects. Burning Man, a nine-day event focused on community, art, and self-reliance held in the temporary desert city of Black Rock, Nevada exemplifies the camp meeting’s social potential.

The camp meeting has its roots in eighteenth century Scottish Presbyterian outdoor ceremonies, later becoming extensive religious revivals, where families built a canvas city around a shared lawn landmarked by a tabernacle for preaching and assembly.32 Camp families sustained themselves, sometimes over an entire summer. Early camps, some accommodating 10,000 people, were the size of neighborhoods, serviced by planned circulation networks, urban blocks, segregated slave quarters, stables for livestock (pre-railroad era), and porches for socializing. By the late nineteenth century with public lighting and modern conveniences, popular revival camps became secularized magical forest cities whose purposes were more social and leisure oriented. The poshest camp meeting was the popular Wesleyan Grove and neighboring resort Oaks Bluff on Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts. In chronicling Martha’s Vineyard’s transition from camp meeting to resort community and eventually incorporated city, Ellen Weiss in City in the Woods writes: “Themes of astonishment, of having been transported from the mundane world into a fairyland, the shock of a miniature city dedicated to joy, pervasive religious feeling, nature, and social density permeated the new decade (1870s), even with the resort’s blatantly commercial edge.” 33 Popular revival camps like Pitman, Mount Tabor, and Ocean Grove in New Jersey enjoyed significant infrastructure investments over time and too became incorporated towns.

While modern camp derivatives saw civic, education, and leisure interests displace religious ones, the atmosphere of the carnival persisted. Camp meeting derivatives included the Chautauqua camps franchised across the U.S. (founded in 1874 as a summer camp for Sunday school teachers at Lake Chautauqua, New York), along with health retreats popularized in the 1880s followed by the resort hotel and the summer youth camp. The Chautauqua movement became an American institution, a center for new ideas combining the arts, the sciences, and public affairs with concerts and theatrical performances attended by tens of thousands of summer residents seeking self-improvement. Cottages were the primary housing form clustered in camps, though sites later accommodated dense hotels and multifamily dwellings compatible with the pedestrian-oriented layout of resort camps. Regardless of meeting purposes, camps shared a common objective to renew the individual through a communal-based retreat to nature.

Similarly, river-based resorts and camps in the Spring River basin reconnected social and natural lifeworlds alienated by the industrial city (Fig. 10). This was especially important in the socialization of middle-class urban youth through summer scouting and the Young Men’s Christian Association/Young Women’s Christian Association (YMCA/YWCA) camps prominent around Cherokee Village. The national rise of the summer youth camp movement since the 1890s was directed at building capacity and character in children without subjecting them to the adult influences of the resort hotel. Memphians formed some of the first scouting troops in the nation and turned to Cherokee Village for camping opportunities. Youth improvement pedagogy combined emulation of frontier soldiers and pioneers with enactment of Indian roles in recovering a sense of authenticity lost to modernity. Scouting was a Progressive Era organization that mixed pioneering ethics and Native American heritage with new skillsets needed for modern commerce and, originally, military service. Scouting was spawned by the fear that skills of survivalism and communal traditions were being lost among city-dwelling youth.34 (Fig. 11.)

As mentioned, Native American motifs like the council ring and tipi became permanent imagery in the camp landscape. In tracing the design development of summer camps, Abigail A. Van Slyck found that after the New Deal in the 1930s, summer camps were thoroughly modernized, though planners worked hard to make them look natural. Camp layout started to reflect the suburb more than the dense urban neighborhoods of the nineteenth-century camp meeting.35 While the camp is an age-old urban form, it uniquely served Americans as a training ground for prototyping new conceptions of social life in an industrializing democracy. Like their northern brethren, popular Ozark camp meeting centers evolved into incorporated cities like nearby Branson, Missouri – now a popular eco-tourist destination nationwide.

Midcentury Planned Communities: Mass Marketing Real Estate

Market segmentation in advertising paralleled the emergence of the nuclear family as a powerful new consumer group with changing needs, including the marketing of new environments tailored to each phase of life. Such specialization in Cherokee Village is ironic, given the Cherokee’s own adaptive practices of polygamy and blending multigenerational households along matrilineal descent responsive to changing circumstances. Cherokee family roles were fluid, egalitarian, and inclusive, where hospitality and reciprocity governed relationships in tribal social organization.36 Cooper marketed heavily to young families. Among his marketing innovations in land sales other than direct mail and free vacations to tour home sites, Cooper formulated graduated land sales and graduated retirement, a theory articulated by Joe Basore, his marketing executive and son-in-law. Basore observed, “what we are doing is just like graduating… first from grade school, then high school, then college. We are selling land for people to play and pay for while they are young, then they are graduating to the next phase – retirement, and then later to apartment or townhouse living. It is graduated living.” 37 Cooper supported a weekly newspaper portraying Village lifestyles, circulated to a national audience of property owners and prospective home buyers.38 Cooper even built an airstrip to fly in prospective property buyers and to support his large traveling sales force.

Special interest communities were a natural continuation of America’s penchant for the camp meeting landscape. The twentieth-century camp, now obligingly organized around a waterfront, gave Cooper the imagery for developing a forest lake community by damming its headwater streams. Drawing upon the tropes of pioneers and Native Americans (Indianness is represented as a ghost in Cooper’s marketing brochures) prevalent in the scouting movement, Cherokee Village marketing material clearly referenced back-to-the-land imagery central to Ozarks tourism (Fig. 12).

Sports activities included hunting, swimming, floating, archery (bowfishing still practiced), and horseback riding through mountain streams and alongside lakes, golf courses, equestrian facilities, marinas, and an airstrip. Cooper pioneered other planning concepts which became standard bearers in the industry. He was the first to use golf fairway frontage for middle-class housing.

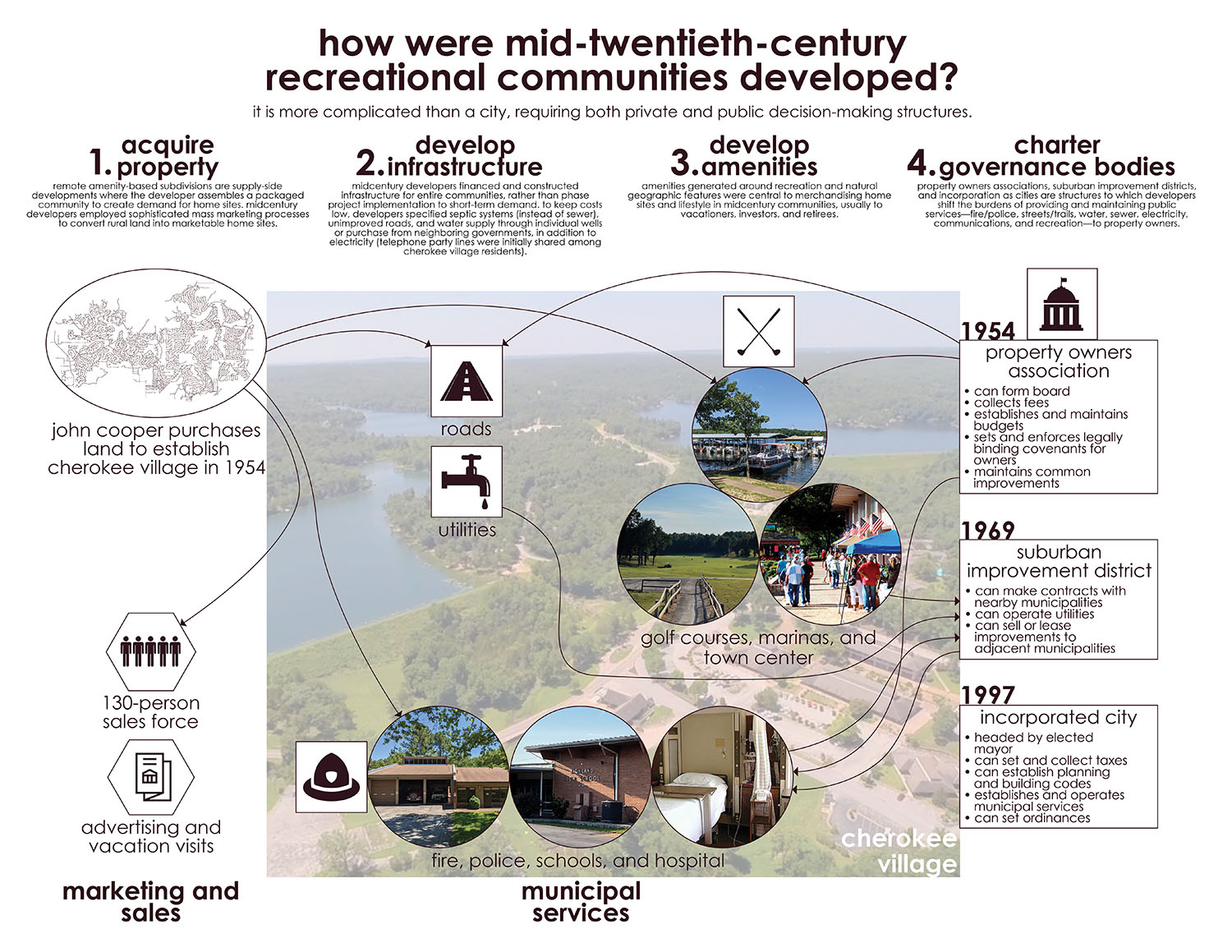

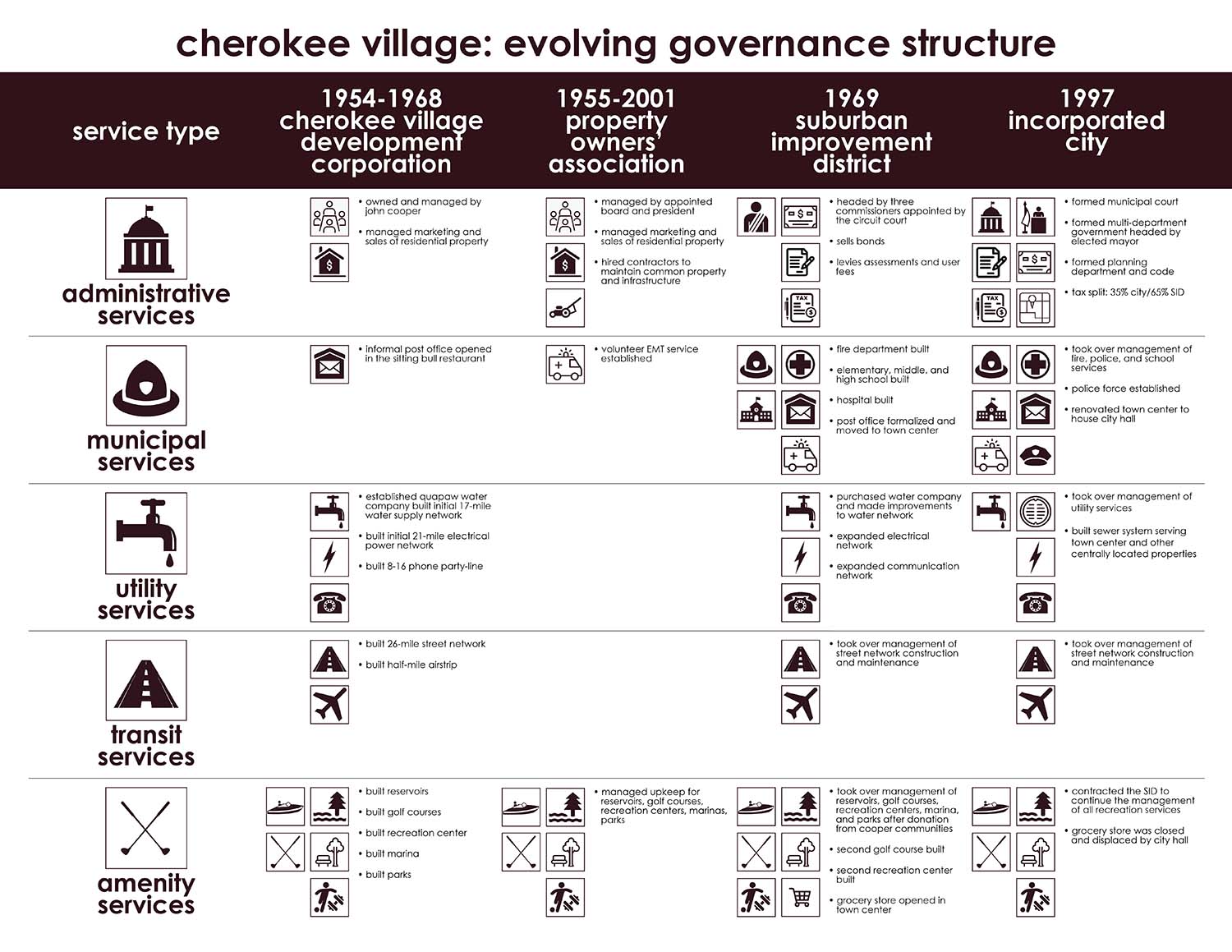

The July 1971 issue of Golf USA recognized John Cooper (not Del Webb) as “the architect of America’s land development industry, and originator of the planned retirement concept which has swept the nation.” 39 Notably, Cherokee Village originated as a rural unincorporated community (i.e., not a city), entailing a novel hybrid governance system in delivering public services. Governance responsibilities were often contested among several entities – Cooper’s development corporation, a property owners association, and a state-enabled suburban improvement district – forty years before Cherokee Village’s incorporation as a city added yet another level of complexity.40 (Figs. 13, 14.)

Cherokee Village’s remoteness forced another innovation in Cooper’s business model – vertical integration of real estate development. In addition to lot sales and financing managed by his real estate company, Cooper owned an engineering and construction company. His operations included a cement plant and concrete block factory to produce drain tile, infrastructural components, and homes.41 Cooper also provided furnishings packages for new homeowners. Cherokee Village even had its own disaster fall-out shelter stocked with a two-week supply of food and water – an example of civil infrastructure rare in speculative community development.

John A. Cooper, Sr. was inducted into the Arkansas Business Hall of Fame in 2004, joining the likes of Sam Walton (Walmart), John Tyson (Tyson Foods), J.B. Hunt (J.B. Hunt Transport Services), William Dillard (Dillard’s), and former Arkansas Governor Winthrop Rockefeller. Cooper opened the nation’s first planned retirement-based recreation community in 1954; and by 1967 his Cherokee Village Development Company was the nation’s fourth largest land developer. According to Witt Stephens, founder of Stephens, Inc., in Little Rock, Arkansas (then-largest brokerage firm off Wall Street), John Cooper “was the man who most changed the face of Arkansas.” 42

Regional Modernism in Design and Planning: Topography, Context, Climate, and Tectonic Form

“Modern building is now so universally conditioned by optimized technology that the possibility of creating significant urban form has become extremely limited… critical regionalism necessarily involves a more directly dialectical relation with nature than the more abstract, formal traditions of modern avant-garde architecture allow.” 43 (Kenneth Frampton)

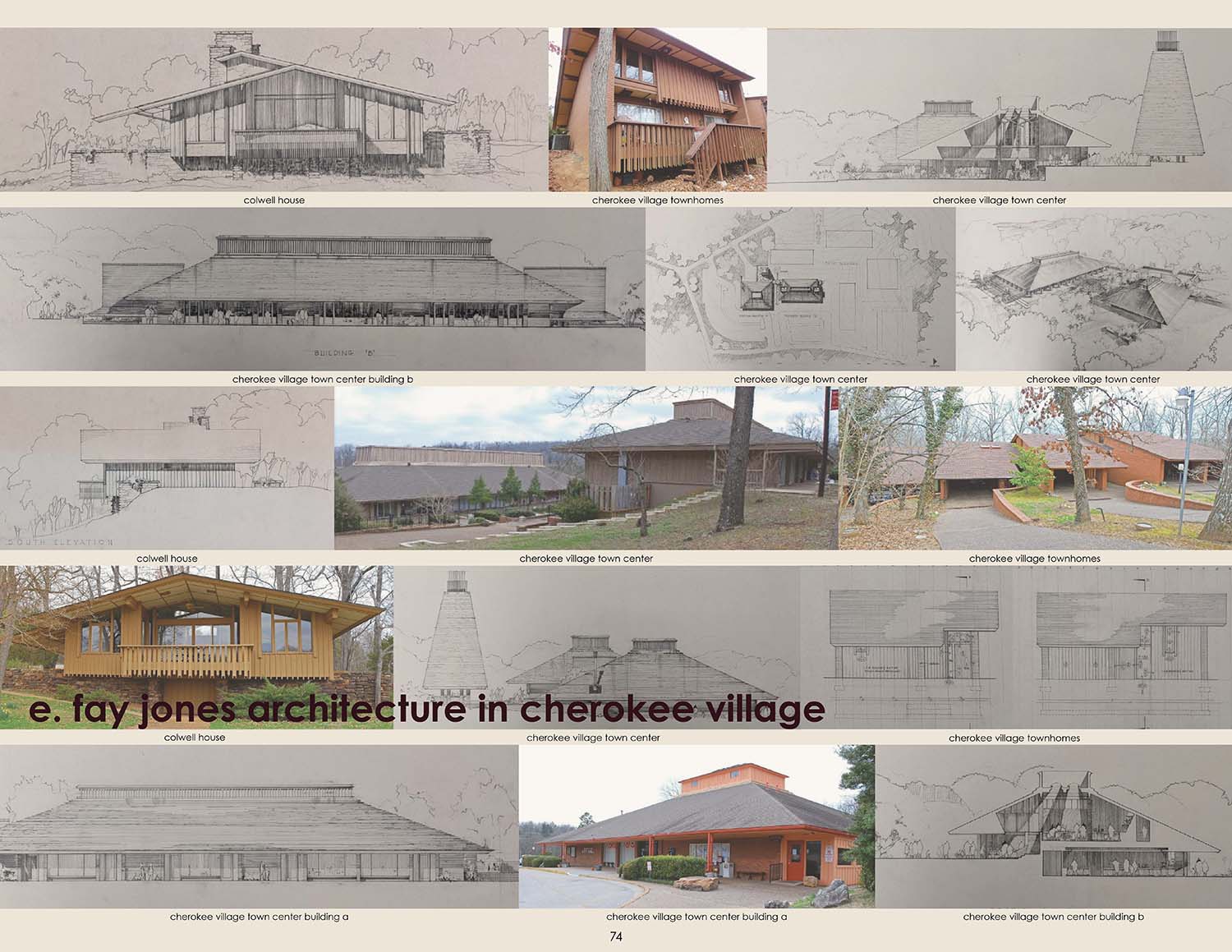

Cooper commissioned award-winning architects who balanced new modernist expressions of space with concern for local topography, context, climate, light, and tectonic form that root buildings to place per Kenneth Frampton’s celebrated notion of critical regionalism. They include 1990 AIA Gold Medalist architect E. Fay Jones (1921-2004). Jones was a young unknown professional when Cooper hired him to design the town center complex and nearby townhouses (Fig. 15).

Cooper became a repeat client. Like his mentor Frank Lloyd Wright, Fay Jones mastered the coordinates with which modern architecture struggled – earth and sky, street and garden, novelty and familiarity, and monumental and human scale. Jones grounded his buildings through a highly formal earthwork of masonry bases and retaining walls that shaped courts and plazas as extensions of interior living spaces. The bustle of the ground was countered by the serenity of a simple but iconic lightweight roofwork of wood with deep overhangs for passive solar control and for sheltering outdoor space. Using natural light to shape interior space, Jones often located skylights at the heart of the building rather than relying solely on the wall for admitting natural light into interior spaces. Windows were never simply punched holes in the walls but rather syntactical systems for organizing the building envelope. Windows are operable and work with skylights and building volume to naturally ventilate indoor space, important before the age of central air conditioning. He skillfully used symmetry to create typologically clear building organizations in service to expressing a poetics of construction fitting of the Ozark landscape. Paradoxically, Jones’ buildings create a convincing environmental continuity often cited as organic architecture yet also stand out as powerful landmarks. He was the Ozark’s signature architect.

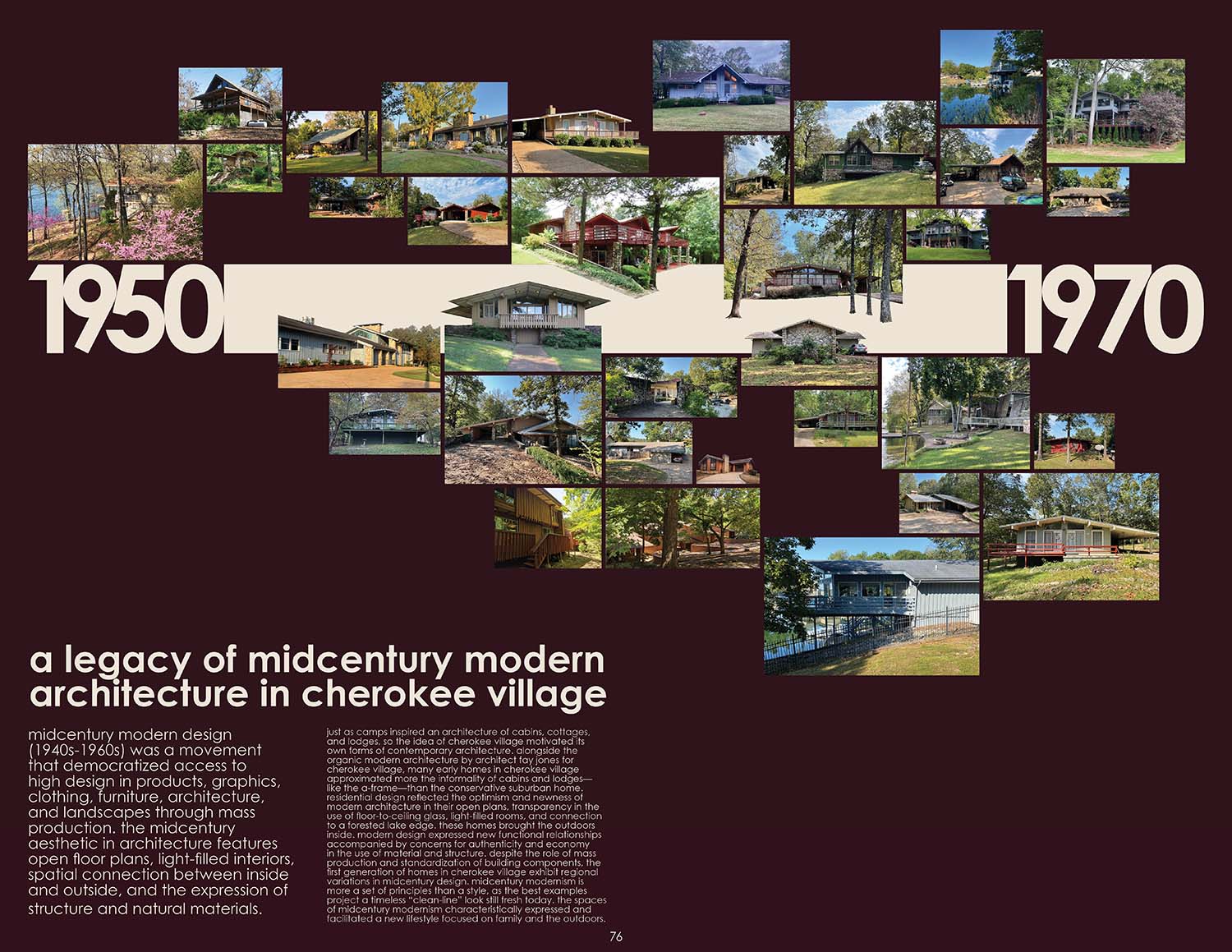

Just as camp meeting formats inspired new urban adaptations of rural cabins, cottages, and lodges, Cherokee Village motivated a regional modernism in its first generation of residential design. Alongside the organic architecture of Fay Jones, early homes in Cherokee Village tempered an orthodox modernism with the rusticity of cabins and lodges, like the A-frame typology. The first generation of residential design in Cherokee Village reflected the optimism and newness of modern architecture in their open floor plans, spatial transparency in the use of floor-to-ceiling glass, light-filled rooms, and orientation to a forested lake edge as well as the street. Modern design expressed new functional relationships accompanied by concerns for authenticity and economy in the use of material and transparent expressions of structure, all while incorporating standardized building components. Homes incorporated passive solar strategies to condition indoor environments. Outdoor decks, responsive to lakefronts and hillside topography, integrated with house forms to extend domestic living space. Architecture brought the outdoors inside. (Fig. 16) Critical regionalism resisted debased and sentimentalized consumer trends through modest interpretations of local forms. Aside from Crestwood Hills in Los Angeles, Hollin Hills in Alexandria, Virginia, and Arapahoe Acres in Englewood, Colorado – all from the late 1940s (see Fig. 3) – Cooper’s Cherokee Village was the rare development in the first generation of postwar community development projects to connect design thinking with placemaking for middle-class housing.

CONCLUSION: HOSPITALITY, THE NEXT ECONOMY

“After a while, a town forgets how to earn its living...”

(Richard C. Longworth) 44

Like Lola Olufemi in her Experiments in Imaging Otherwise, what if we do not expect the map to be a “record of the past or an arrangement of physical space, but, as Mogel and Bhagat write, a topography of procedures? That is, a continuous, fickle, evolving set of processes that eschews definition, or concreteness, or knowing. What if we do not need to know the past, or, indeed, to feel it?” 45 Rather than search for the authorial or a contextualizing authority in the image that gives a thing its history, cultural mapping’s most useful service may be heuristic – an imperfect approach for discovering and generating associations, including the inevitable misreadings which lead to new imaginaries. Olufemi writes, “Here I want to propose a speculative method that anticipates nothing, that does not try to recover context but, instead, lets the image do the work, lets the image make its own argument. I want to begin not with everything-we-do-not-know about the image but all the ways it is self-evident.” 46 Likewise, community planning did not lead us to obvious or symmetrical solutions – recovery of an Indigenous community that was not there (the Cherokee were just passing through and the Osage, who claimed the Arkansas Ozarks as theirs, only used the region for seasonal hunting), or restoration of a pre-development ecology. As it turns out, hospitality is the common thread running throughout Cooper’s buried genealogy of social lifeworlds in organizing place, social structure, and relationships.

What is hospitality’s significance here? More than a mere commercial or perfunctory form, hospitality is a philosophical concept where the guest acquires sovereignty aside a host. In expanding on his description of hospitality through a political and ethical lens, philosopher Jacques Derrida writes, “absolute hospitality requires that I open up my home and that I give not only to the foreigner, but also to the absolute, unknown, anonymous other, and that I give place to them, that I let them come, that I let them arrive, and take place in the place I offer them, without asking of them either reciprocity (entering into a pact) or even their names.” 47 Hospitality is a profound social resource: an imaginary based upon porosity in space, between public and private realms, between the street and its various land uses, and strong and weak ties among diverse populations, all anathema to zoning. Hospitality is a form of resilience, where the stranger is not a threat, but an additional source of cooperation, where social codes and hierarchies give rise to evolutionary forms of habitation rather than a premature fix to untested and now seemingly inferior conditions like the zoned suburb.

Suburban hegemony admits no informal tenancy found in the organic community – those shared co-living economies or communal housing solutions that affordably sheltered waves of working-and-middle-class populations migrating through the early twentieth century industrial city. Midcentury land-use regulations outlawed the pre-WWII portfolio of housing-neighborhood complexes where the bed rather than the house was the minimum unit of dwelling.48 Such innovative living formats included residential hotels, the bungalow court, single-room occupancy hotels (SROs), co-living complexes, live-work dwellings, room-and-board residences, and forms of missing middle housing. Too, the once common intergenerational household, an incredibly resilient social structure, was zoned out as a non-conforming lifestyle by midcentury municipal policy.

This was all quite revolutionary, as architectural historian Niklas Maak recalls in Living Complex: From Zombie Cities to the New Communal. “For millennia, building complexes were the rule and significantly more than four related people, on average, lived in them together, whether they were farmsteads or palaces or bourgeois townhouses. What seems like an experimental residential commune to us today was the norm.” 49

By midcentury, America’s generous and diverse housing supply had been replaced by atomized real estate products – single-family houses – legislated, financed, and motivated by what Maak calls a social “pathology of privacy.” 50 A pathology or White fragility that fortresses home buyers from changing social, economic, and technological futures, often rendering their communities vulnerable to obsolescence and the capacity to adapt. Yet, as Maak reflects things change, “the private and public are not basic anthropological constants either, but rather historically established concepts subject to social and technological change.” 51 Thus, we consider Cherokee Village to be an incomplete project.

Cultural mapping as a framing mechanism is the onset of planning.52 The deep map or memoir of Cherokee Village harbored a genealogy of associations that reoriented the planning process for Cherokee Village away from the lazy reliance on market feasibility analyses and data projections based on comparables (comps), and toward scenario thinking. Inspired by the hospitality intrinsic to Indigenous, subsistence settler, camp meeting, and scouting traditions, scenario planning for Cherokee Village embraced cooperative forms of living unearthed in cultural mapping to address big challenges ahead. Prevailing economic and social precarity, now describing a supermajority of the American population, requires hospitality and forms of cooperation as a planning episteme. Cooperativity as a socio-economic orientation entails regard for the constellation of pluriversal traditions and their dividends. They include more complex habitologies related to informal neighborhood housing formats, new roles for care and reciprocity in development, social and functional porosity (vs. zoning), social capacities, and reparative planning (equitable, environmental, and social). Cherokee Village’s Framework Plan is premised on this much needed ethic of repair.

Wolfgang Sachs, “Forward: The Development Dictionary Revisited,” in Pluriverse: A Post-development Dictionary, eds. AshishKothari, Ariel Salleh, Arturo Escobar, Federico Demaria, and Alberto Acosta (New Delhi, India: Tulika Books, 2019), xi.

Eric H. Monkkonen, America Becomes Urban: The Development of US Cities & Towns 1780-1980 (Berkeley CA, USA: University of California Press, 1988), 4.

“The Cultural Landscape Foundation,” accessed September 30, 2021 – https://www.tclf.org/places/about-cultural-landscapes. According to the CLF, there are four types of cultural landscapes: designed landscapes, ethnographic landscapes, historic sites, and vernacular landscapes. Cherokee Village is a designed landscape.

“US Census Bureau (2019),” American Community Survey 5‑Year Estimates. US Department of Commerce, September 30, 2021 – https://data.census.gov/.

Richard Florida, “How Some Shrinking Cities Are Still Prospering,” CityLab (June 13, 2019) – https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-06-13/some-cities-are-getti....

Judith Ann Trolander, “Del Webb’s ‘Sun City’ Concept,” in From Sun Cities to the Villages: A History of Active Adult, Age-Restricted Communities (Gainesville FL, USA: University Press of Florida, 2011), 47-81.

“America’s Land Development Industry,” Arkansas State Magazine (Spring 1967), 12-17, 43, 44, 46.

See essays in Cherokee Village Historical Society, Early “History” of Cherokee Village (Salem AR, USA: Areawide Media News Printing, 2005).

Quoted in Ashish Kothari et al., “Introduction: Finding Pluriversal Paths,” in Pluriverse: A Post-development Dictionary, xxxiii.

Nancy Duxbury, W.F. Garrett-Petts, and Alys Longley, “An Introduction to the Art of Cultural Mapping: Activating Imaginaries and Means of Knowing,” in Nancy Duxbury et al. (eds.) Artistic Approaches to Cultural Mapping: Activating Imaginaries and Means of Knowing (Abingdon-on-Thames, UK: Routledge, 2019), 3.

John Durham Peters, The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2015), 1-12.

William Least Heat-Moon, PrairyErth (A Deep Map) (New York: Mariner Books, 1999).

Mike Pearson and Michael Shanks, Theatre/Archaeology (London: Routledge, 2001), 64-65. Quoted in Ines de Carvalho and Deirdre Denise Matthee, “Other Lives and Times in the Palace of Memory: Walking as a Deep-Mapping Practice” in Artistic Approaches, eds. Duxbury et al., 122.

Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven F. Rendell (Berkeley CA, USA: University of California Press, 1984), 129.

Clarissa Rile Hayward, How Americans Make Race: Stories, Institutions, Spaces (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 3.

The Timely Club, The Hardy History (Hardy AR, USA: Riverside Graphics, 1980).

Tish Talbot, “John A. Cooper, Sr: A Vision of and for Tomorrow”, Arkansas Times (March 1983), 31-40. Insights by John Cooper are all drawn from secondary sources as writings and correspondences by John Cooper are not available to the public. The family company, Cooper Communities is ongoing and located in Rogers, Arkansas.

Philip J. Deloria, Playing Indian (New Haven CT, USA: Yale University Press), 90.

See especially David C. Scott and Brendan Murphy, The Scouting Party: Pioneering and Preservation, Progressivism and Preparedness in the Making of the Boy Scouts of America (Dallas: Red Honor Press, 2010); Leslie Paris, Children’s Nature: The Rise of the American Summer Camp (New York: New York University Press, 2008); and Abigail A. Van Slyck, A Manufactured Wilderness: Summer Camps and the Shaping of American Youth, 1890-1960 (Minneapolis MN, USA: University of Minnesota Press, 2006).

Paris, Children’s Nature, 9.

Deloria, Playing Indian, 101.

For common racialized perceptions of Native Americans, see Roxanne Dubar-Ortiz and Dina Gilio-Whitaker, “All the Real Indians Died Off” and 20 Other Myths about Native Americans (Boston: Beacon Press, 2016).

The Trail of Tears passed nearby but Cherokees had not settled in the area, as it was Osage hunting ground. Brooks Blevins, “History of the Ozarks and Local Pioneer Culture” (public lecture in Cherokee Village, October 25, 2021).

Brooks Blevins, Arkansas/Arkansaw: How Bear Hunters, Hillbillies, & Good Ol’ Boys Defined a State (Fayetteville AR, USA: The University of Arkansas Press, 2009), 39.

Brooks Blevins, Hill Folks: A History of Arkansas Ozarkers and Their Image (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 89.

Lynn Morrow and Linda Myers-Phinney, Shepherd of the Hills Country: Tourism Transforms the Ozarks, 1880s-1930s (Fayetteville AR, USA: The University of Arkansas Press, 1999).

Blevins, Hill Folks.

Van Slyck, A Manufactured Wilderness, 4-5.

Charlie Hailey, Camps: A Guide to 21st-Century Space (Cambridge MA, USA: The MIT Press, 2009), 9.

Ibid., 3.

Trolander, From Sun Cities to the Villages, 45.

For an excellent history of camp meeting, see Ellen Weiss, City in the Woods: The Life and Design of an American Camp Meeting on Martha’s Vineyard (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1998). See also Sara N. Hines, Cottage Communities – the American Camp Meeting Movement: A Study in Lean Urbanism (Ashland MA, USA: Hines Art Press, 2015).

Weiss, City in the Woods, 113.

ohn Phillips, “Selling America: The Boy Scouts of America in the Progressive Era, 1910-1921” (master’s thesis, The University of Maine, 2001), 205 – http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/205.

For an excellent history chronicling the evolution of summer camp design, see Van Slyck, A Manufactured Wilderness.

Not unlike many tribal nations, the Cherokee family was expansive and resilient in its communitarian-based approach to household formation, and in confronting climate challenges, resource constraints, and conflict including colonization – what ecologist Robin Wall Kimmerer calls the “ethic of the longhouse” (symbolizing family, unity, and togetherness in the Iroquois or Haudenosaunee tradition) in Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants (Minneapolis MN, USA: Milkweed Editions, 2015). For Cherokee family structure see, Rose Stremlau, Sustaining the Cherokee Family: Kinship and the Allotment of an Indigenous Nation (Chapel Hill NC, USA: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011).

Ray Speckman, The Cooper Communities: A Walk with History, unpublished, 20.

Bill Ligon, “Village Editor” in Cherokee Village Historical Society, Early “History” of Cherokee Village, 78.

Talbot, “John A. Cooper, Sr.”

For more on the operational framework of unincorporated recreational-based planned communities, see Hubert B. Stroud, The Promise of Paradise: Recreational and Retirement Communities in the US since the 1950s (Baltimore MD, USA: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), especially 12-13.

“America’s Land Development Industry,” Arkansas State Magazine.

Witt Stephens quoted in Speckman, The Cooper Communities, 37.

Kenneth Frampton, “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance,” in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, ed. Hal Foster (Port Townsend WA, USA: Bay Press, 1983), 16-30.

Richard C. Longworth, Caught in the Middle: America’s Heartland in the Age of Globalism (New York: Bloomsbury USA, 2008), 47.

Lola Olufemi, Experiments in Imagining Otherwise (London: Hajar Press, 2021), 18-9.

Ibid., 20.

Jacques Derrida and Anne Dufourmantelle, Of Hospitality, trans. Rachel Bowlby (Stanford CA, USA: Stanford University Press, 2000), 25.

Ariel Aberg-Riger, “When America’s Basic Housing Unit Was a Bed, Not a House,” CityLab (February 22, 2018) – https://www.citylab.com/equity/2018/02/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-american....

Niklas Maak, Living Complex: From Zombie Cities to the New Communal (Munich, Ger.: Hirmer Publishers, 2015), 26.

Ibid., 160.

Ibid., 166.

To view the Cherokee Village Framework Plan and report, see University of Arkansas Community Design Center – https://uacdc.uark.edu/work/2023/05/16/cherokee-village-framework-plan.

I express my deepest gratitude to our partners in Cherokee Village on both the cultural mapping and scenario planning initiatives. Thanks especially to Jonathan Rhodes and his exceptional leadership in developing this project with the National Endowment for the Arts. It was certainly a watershed project for our center, and one in which we did not entirely fathom what we were getting into. Many thanks to the National Endowment for the Arts for your support and technical assistance on this important project.

All images are by the University of Arkansas Community Design Center unless otherwise listed.

Figure 1:

man fishing below dam

“scenic publications.” hardy: arkansas, n.d.

dam, picnic tables in foreground

rhodes, jonathan. american land co, n.d.

dam, riders on horseback in foreground

cherokee village historical society. there is a mountain home for you at cherokee village on the south fork river, hardy, arkansas, n.d.

dam, rider on horseback with steer in foreground

rhodes, jonathan. american land co, n.d.

dam spillway

rhodes, jonathan. american land co, n.d.

dam, hunter holding antlers and woman with deer in foreground

“scenic publications.” hardy: arkansas, n.d.

dam, canoe and plane on lake in foreground

rhodes, jonathan. american land co, n.d.

Figure 2:

ravenden springs

wahpeton inn on the bluff

“wahpeton inn.” pinterest, may 11, 2019. https://www.pinterest.com/pin/4714774596446821/

southern hotel ravenden springs

“the southern hotel, ravenden springs.” five rivers historic preservation. (http://www.5rhp.org/southern.jpg:

accessed november 8, 2022; site inactive on 27 february 2023).

wahpeton inn resort

“wahpeton inn news.” pinterest, july 22, 2015. https://www.pinterest.com/pin/197736239866214637/

cabins at old kia kima

“history of old kia kima.” old kia kima. accessed february 27, 2023. https://www.oldkiakima.org/okk_history.php

tbird lodge at old kia kima

“about old kia kima.” old kia kima. accessed february 27, 2023. https://www.oldkiakima.org/

crystal river cave camp

“cave city area origins.” cave city, arkansas. accessed february 27, 2023. https://www.cavecity.us/our-history

girl scout camp miramichee

“c.1935 stone home with lake view in hardy arkansas under $48k ~ off market.” old houses under $50k, november 16, 2019. https://oldhousesunder50k.com/c-1935-stone-home-with-lake-view-in-hardy-...

chapel at old kia kima

“history of old kia kima.” old kia kima. accessed february 27, 2023. https://www.oldkiakima.org/okk_history.php

dining hall at old kia kima

morton, fred. “kia kima at the beginnings of scouting in memphis.” old kia kima. accessed february 27, 2023. https://www.oldkiakima.org/okk_beginning.php

rose hill resort

“rose hill resort.” pinterest, april 8, 2018. https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/659707045389939695/

tbird lodge inside at old kia kima

“photo gallery.” old kia kima. accessed february 27, 2023. https://www.oldkiakima.org/okk_pictures.php

youth swimming in the spring river

morton, fred. “kia kima at the beginnings of scouting in memphis.” old kia kima. accessed february 27, 2023. https://www.oldkiakima.org/okk_beginning.php

Figure 3:

imbert, dorothee. “the art of social landscape design.” university of california press. accessed february 27, 2023. https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docid=ft6g50073x%3bchunk.id

crestwood hills_jonesmhaview

“a. quincy jones & whitney smith house - los angeles, ca.” frank lloyd wright building conservancy. accessed february 27, 2023. http://wrightchat.savewright.org/viewtopic.php?p=108517

crestwood hills

“mha site office: a. quincy jones, whitney r. smith 1947.” open space, may 15, 2019. https://openspaceseries.com/blog/the-mha-site-office-a-quincy-jones-whit...

hollin hills_hollin hills virginia

“hollin hills.” hollin hills. accessed february 27, 2023. https://www.hollin-hills.org/

hollin hills

“029-5471 hollin hills historic district.” dhr virginia department of historic resources. accessed february 27, 2023. https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/historic-registers/029-5471/

hollin hills

“10 things: hollin hills, va.” claass haus, september 20, 2018. https://www.claasshaus.com/blog/10-things-hollin-hills-va

hollin hills

“mid-century hollin hills and mad men.” sunshine+design, july 25, 2010. https://sunshineanddesign.wordpress.com/2010/07/25/hollin-hills-mad-men/

arapahoe acres

“arapahoe acres.” arapahoe acres | the cultural landscape foundation. accessed february 27, 2023. https://www.tclf.org/landscapes/arapahoe-acres

arapahoe acres

“arapahoe acres.” arapahoe acres | the cultural landscape foundation. accessed february 27, 2023. https://www.tclf.org/landscapes/arapahoe-acres

arapahoe acres

“arapahoe acres.” arapahoe acres | the cultural landscape foundation. accessed february 27, 2023. https://www.tclf.org/landscapes/arapahoe-acres

Figure 4:

boulevard kamp kiwani

“1920 photo: boulevard kamp kiwani.” kia kima alumni association museum. accessed february 23, 2023. https://www.kiakimamuseum.org/items/show/467#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-79%2c-6...

1948 handbook for boys

schilling, vincent. “order of the arrow is a ‘secret’ scout society ‘in the spirit of the lenni lenape’ - a lenape leader disagrees.” ict. the arena group, september 16, 2019. https://ictnews.org/news/order-of-the-arrow-is-a-secret-scout-society-in...

1989 oa section conclave

chickasah lodge, “1989 oa section conclave (kia kima program),” kia kima alumni

association museum. accessed february 23, 2023,

https://www.kiakimamuseum.org/items/show/657

chickasaw dance and drum team

“photo: chickasah lodge dance and drum team,” kia kima alumni association museum.

accessed february 23, 2023, https://www.kiakimamuseum.org/items/show/1042

kia kima totem pole

fred carney, “1935 photo: kia kima totem pole,” kia kima alumni association museum.

accessed february 23, 2023, https://www.kiakimamuseum.org/items/show/743

scout show pow wow

press-scimitar, “1968 photo: scout show pow wow - pinky pratt, richard stevens, bill

rosen,” kia kima alumni association museum. accessed february 23, 2023, https://www.kiakimamuseum.org/items/show/647

chickasaw council silver beaver recipients

“1952 photo: chickasaw council silver beaver recipients,” kia kima alumni association

museum. accessed february 23, 2023,

https://www.kiakimamuseum.org/items/show/1035

chickasaw lodge regalia hiriam maynard

press-scimitar, “1975 photo: chickasah lodge regalia hiriam maynard,” kia kima alumni

association museum. accessed february 23, 2023,

https://www.kiakimamuseum.org/items/show/648

kia kima dancers

“1958 photo: kia kima dancers at fouth of july celebration,” kia kima alumni association

museum. accessed february 23, 2023, https://www.kiakimamuseum.org/items/show/759

buffalo bill’s wild west

“buffalo bill wild west show.” pinterest, november 14, 2018. https://www.pinterest.com/maryolm/wild-west/buffalo-bill-wild-west-show/

pawnee bills wild west

chester, molly. “the wild west? apush.” smithsonian learning lab. accessed february 28, 2023. https://learninglab.si.edu/collections/the-wild-west-apush/ud13xubfn5bgv...

the lone ranger

fox, courtney. “'the lone ranger': clayton moore made a masked man a western icon.” wide open country, june 7, 2021. https://www.wideopencountry.com/clayton-moore-lone-ranger/

the lone ranger comic

“the lone ranger #133.” my comic shop. accessed february 23, 2023. https://www.mycomicshop.com/search?minyr=1956&maxyr=1969&tid=192121&pgi=101

the squaw man

“file : william faversham in the squaw man lccn2014635472.jpg.” wikimedia commons. accessed february 23, 2023. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/file:william_faversham_in_the_squaw_m...

gunsmoke

“gunsmoke annual 1974.” gunsmoke. accessed february 23, 2023. https://www.gunsmokenet.com/gunsmoketgaw/marks-stuff/gunsmoke/collectabl...

gun the man down

“self-defense - gun the man down - 1956 - andrew v. mclaglen.” western movies forum. accessed february 23, 2023. https://forum.westernmovies.fr/viewtopic.php?p=350417#p350417

gunsmoke

“shona - gunsmoke (season 8, episode 20): apple tv.” apple tv, accessed 2023. https://tv.apple.com/us/episode/shona/umc.cmc.5kbjnblixhejf85ba58h2s4t1?...

washington redskins

“washington redskins.” pinterest, october 4, 2015. https://www.pinterest.com/pin/502151427181091222/

mlb cleveland all-star logo

“mlb all-star game logo .” chris creamer's sportslogos.net. accessed february 23, 2023. https://www.sportslogos.net/logos/view/2943/_mlb_all-star_game/1963/prim...

cleveland indians face paint

riedel, charlie. “a cleveland indians fan poses for a picture before game 1 of the major league baseball world series against the chicago cubs tuesday in cleveland. daily news.” accessed february 23, 2023. https://www.dailynews.com/wp-content/uploads/migration/2016/201610/news_...

chief illiniwek dances at illinois game

“chief illiniwek dances on the court at an illinois basketball game for the last time on feb. 21, 2007.” accessed february 23, 2023. https://www.gannett-cdn.com/authoring/2018/01/29/nsjr/ghows-ls-63ee3661-...

native american dwelling

yost, russell. “guide to native american life.” the history junkie, january 9, 2020. https://thehistoryjunkie.com/guide-to-native-american-life/

inside of a longhouse

freda, tom. inside of a longhouse. tom freda photography. accessed february 23, 2023. https://www.tomfreda.com/

last of the mohicans

“the last of the mohicans.” biblio. accessed february 23, 2023. https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/705/801/881801705.0.m.2.jpg

iron eyes cody and president jimmy carter

dunaway, finis. “the ‘crying indian’ ad that fooled the environmental movement.” zócalo public square, november 7, 2017. https://www.zocalopublicsquare.org/2017/11/09/crying-indian-ad-fooled-en...

pocahontas

“disney princess article: pocahontas: the princess with personality.” fanpop. accessed february 23, 2023. https://www.fanpop.com/clubs/disney-princess/articles/228352/title/pocah...

pollution ad

kaplan, aline. “changing cultural norms step by step.” the next phase blog, october 10, 2017. https://aknextphase.com/tag/keep-america-beautiful/

canoeing

“keep america beautiful.” pinterest, august 12, 2013. https://www.pinterest.com/ldover15/keep-america-beautiful/

cherokee casino

“harrah's cherokee poised to complete $250m project.” casinobeats, june 24, 2021. https://casinobeats.com/2021/06/24/harrahs-cherokee-poised-to-complete-2...

Figure 5:

mopac depot cotter arkansas

parker houghton, jeana. “marion co, arkansas' genealogy.” marion county usgen web. accessed february 27, 2023. https://www.argenweb.net/marion/index.html

frisco railroad to mempis to hardy

“‘frisco’ railway near hardy.” encyclopedia of arkansas, september 29, 2022. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/media/st-louis%c2%96san-francisco-rai...

courtesy of the butler center for arkansas studies, central arkansas library system

workers at black rock button factory

“black rock buttons.” ozark county times, (https://www.ozarkcountytimes.com/%20from%20%20arkansas%20fish%20and%20ga... accessed November 7, 2022; site inactive on 27 february 2023)

frisco engine 183 passenger train from memphis to kansas city

“the frisco: a look back at the saint louis-san francisco railway.” the library. accessed february 27, 2023. https://thelibrary.org/lochist/frisco/frisco.cfm

pearling camp

“pearling camp.” encyclopedia of arkansas, (http://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/media-detail.aspx?mediaid.... accessed November 7, 2022; site inactive on 27 february 2023). courtesy arkansas state university museum

hoxie depot

“hoxie depot.” encyclopedia of arkansas, may 27, 2022. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/media/hoxie-depot-11383/. courtesy of the butler center for arkansas studies, central arkansas library system

ozark queen, cotter 1897

“steamboat ozark queen.” pinterest, july 24, 2018. https://www.pinterest.com/pin/105975397467063102/

yellville downtown

“cotter heritage.” trout capital usa. accessed february 27, 2023. http://www.troutcapitalusa.net/heritage.html

morning side mine rush arkansas

parker houghton, jeana. “marion co, arkansas' genealogy.” marion county usgen web.

accessed february 27, 2023. https://www.argenweb.net/marion/index.html

calico rock downtown

“calico rock; late 1800s.” encyclopedia of arkansas, september 30, 2022. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/media/calico-rock-1800s-11388/. courtesy of the butler center for arkansas studies, central arkansas library system

ozark queen

“vintage photos: gorby.” exploring izard county, march 5, 2020. http://exploreizard.blogspot.com/

glass and sand mine guion

“guion sand mine.” encyclopedia of arkansas, may 27, 2022. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/media/guion-izard-county-sand-mine-8683/

cushman manganese mining operation

“w. h. denison; contractor.” encyclopedia of arkansas, september 29, 2022. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/media/w-h-denison-contractor-11038/

batesville downtown

“batesville history.” city of batesville, may 8, 2015. https://www.cityofbatesville.com/about-batesville/history/

florence meyer with 450 tons of cotton

“florence meyer with 450 tons of cotton, batesville 1880.” university of wisconsin-madison libraries. accessed february 27, 2023. https://asset.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/klzq76a2zg5al8s/m/h1380-84d8a.jpg

bales of cotton being loaded to steamboat, v.y. cook plantation 1881

huddleston, duane; sammie, rose; and wood, pat. steamboats and ferries on white river: a heritage revisited, university of central arkansas press: 1995. courtesy of the university of arkansas, little rock archives and special collections

long boat sears circa 1920

huddleston, duane; sammie, rose; and wood, pat. steamboats and ferries on white river: a heritage revisited, university of central arkansas press: 1995. photo courtesy of jacksonport courthouse museum

jennie howell with 2456 bales of cotton

“steamboat jennie howell loaded with cotton.” louisiana digital library. accessed february 27, 2023. https://louisianadigitallibrary.org/islandora/object/hnoc-clf:4495

ironclad u.s. gunboat st. louis

“fort henery: u.s. gun boat st. louis.” fort henry. accessed february 27, 2023. http://ushistoryimages.com/fort-henry.shtm

tender for dredges 1898

“blueprints.” online steamboat museum dave thomson collection. accessed february 27, 2023. https://steamboats.com/museum/davet-ephemerablueprints.html

pocahontos hauling log barge, black river 1915

huddleston, duane; sammie, rose; and wood, pat. steamboats and ferries on white river: a heritage revisited, university of central arkansas press: 1995. photo courtesy of wilson powell

Figure 7:

ceremony speaker

Photograph. Eastern Arkansas Area Council Historical Preservation Society. Cedar Valley Alumni Association, 1970. http://eaac.org/photoalbum/Hi%20Lo%20Ha%20Chy%20A-La%20Lodge/Images/70-0...

ceremony outfits

Photograph. Eastern Arkansas Area Council Historical Preservation Society. Cedar Valley Alumni Association. http://eaac.org/photoalbum/Hi%20Lo%20Ha%20Chy%20A-La%20Lodge/Images/XX-0...

ceremony entrance

Photograph. Eastern Arkansas Area Council Historical Preservation Society. Cedar Valley Alumni Association, 1974. http://eaac.org/photoalbum/Hi%20Lo%20Ha%20Chy%20A-La%20Lodge/Images/74-0...

ceremony costume

Photograph. Eastern Arkansas Area Council Historical Preservation Society. Cedar Valley Alumni Association, 1975. http://eaac.org/photoalbum/Hi%20Lo%20Ha%20Chy%20A-La%20Lodge/Images/75-0...

oa sashes

Photograph. Eastern Arkansas Area Council Historical Preservation Society. Cedar Valley Alumni Association, 1956. http://eaac.org/photoalbum/Hi%20Lo%20Ha%20Chy%20A-La%20Lodge/Images/56-0...

dancers 1

Photograph. Eastern Arkansas Area Council Historical Preservation Society. Cedar Valley Alumni Association, 1981. http://eaac.org/photoalbum/Hi%20Lo%20Ha%20Chy%20A-La%20Lodge/Images/81-0...

dancers 2

Photograph. Eastern Arkansas Area Council Historical Preservation Society. Cedar Valley Alumni Association, 1981. http://eaac.org/photoalbum/Hi%20Lo%20Ha%20Chy%20A-La%20Lodge/Images/81-0...

dancers 3

Photograph. Eastern Arkansas Area Council Historical Preservation Society. Cedar Valley Alumni Association, 1981. http://eaac.org/photoalbum/Hi%20Lo%20Ha%20Chy%20A-La%20Lodge/Images/81-0...

dancers 4

Photograph. Eastern Arkansas Area Council Historical Preservation Society. Cedar Valley Alumni Association, 1981. http://eaac.org/photoalbum/Hi%20Lo%20Ha%20Chy%20A-La%20Lodge/Images/81-0...

dancers 5

Photograph. Eastern Arkansas Area Council Historical Preservation Society. Cedar Valley Alumni Association, 1981. http://eaac.org/photoalbum/Hi%20Lo%20Ha%20Chy%20A-La%20Lodge/Images/81-0...

old white flap patch

Photograph. Eastern Arkansas Area Council Historical Preservation Society. Cedar Valley Alumni Association. http://eaac.org/OA/images/F1-F1.jpg

the shield patch

Photograph. Eastern Arkansas Area Council Historical Preservation Society. Cedar Valley Alumni Association. http://eaac.org/OA/images/X1a-X1a.jpg

vigil blanket patch

Photograph. Eastern Arkansas Area Council Historical Preservation Society. Cedar Valley Alumni Association. http://eaac.org/OA/images/J6-J5.jpg

Figure 8:

lassale's party at the village of the illinois

sabo, george. “indians and colonists.” arkansas archeological survey. accessed february 23, 2023. http://archeology.uark.edu/indiansofarkansas/printerfriendly.html?pagena...

detail from "lasalle's party feasted in the village of the illinois, january 2, 1680" by george catlin. ©1997 board of trustees, national gallery of art, washington (paul mellon collection).

quopow trade dumont de monligny

sabo, george. “indians and colonists.” arkansas archeological survey. accessed february 23, 2023. http://archeology.uark.edu/indiansofarkansas/printerfriendly.html?pagena...

henri de tonti's post on the arkansas. courtesy of the arkansas historical commission.

parker family ranch

morrow, lynn. “newton country, arkansas.” ozarkswatch. accessed february 23, 2023. https://thelibrary.org/lochist/periodicals/ozarkswatch/ow204e.htm

first bale of cotton

“mountain home cotton.” encyclopedia of arkansas, may 27, 2022. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/media/mountain-home-cotton-8630/

cook plantation

“cook's landing.” encyclopedia of arkansas, may 27, 2022. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/media/cooks-landing-14744/

re ark marble quarry of white river

“list of quarries in arkansas & quarry links, photographs and articles.” stone quarries and beyond. accessed february 23, 2023. http://quarriesandbeyond.org/states/ar/ar-photos_1.html

cotton wagons

“1900's – cotton wagons in downtown newport circa 1900.” jackson county historical society. arcadia publishing, 2016. https://jacksonhistory.net/cotton-wagons-in-downtown-newport-circa-1900/

settlement of arkansas post

“colonial arkanasas post ancestry.” university of arkansas libraries digital collections. accessed february 23, 2023. https://digitalcollections.uark.edu/digital/collection/capa

quopow trade dumont de monligny 2

“trade goods.” arkansas archeological survey. accessed february 23, 2023. http://archeology.uark.edu/indiansofarkansas/index.html?pagename=trade+g.... courtesy of the newberry library, chicago

carter county homestead