Professor in Residence, Department of Architecture, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

This article focuses on the French architect Claude Parent’s exploration of oblique architecture during a series of traveling programs pursued between 1969 and 1975. Based on a theory of the inclined plane developed in the 1960s with Paul Virilio as part of the group Architecture Principe, Parent conducted this exploration through temporary installations and staged public events hosted by cultural centers throughout France. This article examines the institutional context within which Parent’s traveling repertoire took place as well as the government policies, social movements, and cultural forces that shaped it. Through such an approach, the article develops a perspective on the relationship between Parent’s practice and the cultural centers’ objectives as mutually beneficial, and of his interventions as site specific, both architecturally and socially. The article furthermore provides evidence that these participatory experiences had a lasting effect on the architect’s attitude toward experimental architecture, shifting his priorities from form to subject.

During the 1960s the French architect Claude Parent collaborated with Paul Virilio as part of Architecture Principe, a group they cofounded with the initial involvement of other artists. The group’s distinguishing achievement was the development of a theory preoccupied with the use of inclined planes in architecture, known as the oblique function.1 Although it lasted only a few years—from 1963 to approximately 1968—Parent and Virilio’s collaboration yielded a substantial body of work consisting of publications, exhibitions, speculative works, as well as built commissions through which they explored various forms of oblique architecture.2 The general premise of their theory was that slanting or angling typically level architectural elements like floors—and more generally the ground—moved people into a deeper engagement with their physical environment, while at the urban scale diagonal geometries offered the preferred alternative to both horizontal expansion and vertical growth of cities. Architecture Principe’s theory reflected an interest in what the architectural critic Jacques Lucan explains as “a Gestalt psychology of form, which promoted continuous, fluid movement and forced the body to adapt to instability.” 3

Through their joint endeavors, Parent and Virilio argued that in order to be socially relevant, architecture needed to reflect the dynamic nature of contemporary life. In this way, they considered the inclined plane to be the ultimate expression of “the new plane of human consciousness.” 4 Among the group’s most significant achievements were two artifacts: a serial publication and a religious building. The former, the eponymous self-published magazine with a total run of nine issues,5 consisted of a series of provocations about the future of architecture, captured in strikingly drawn images of oblique architectural forms accompanied by manifesto-style writing. The latter artifact is Architecture Principe’s Church of St Bernadette of Banlay in Nevers, an equally provocative concrete bunkerlike building with a sloped nave completed in 1966 and recognized, since 2000, as a historic monument.6 (Fig. 1.)

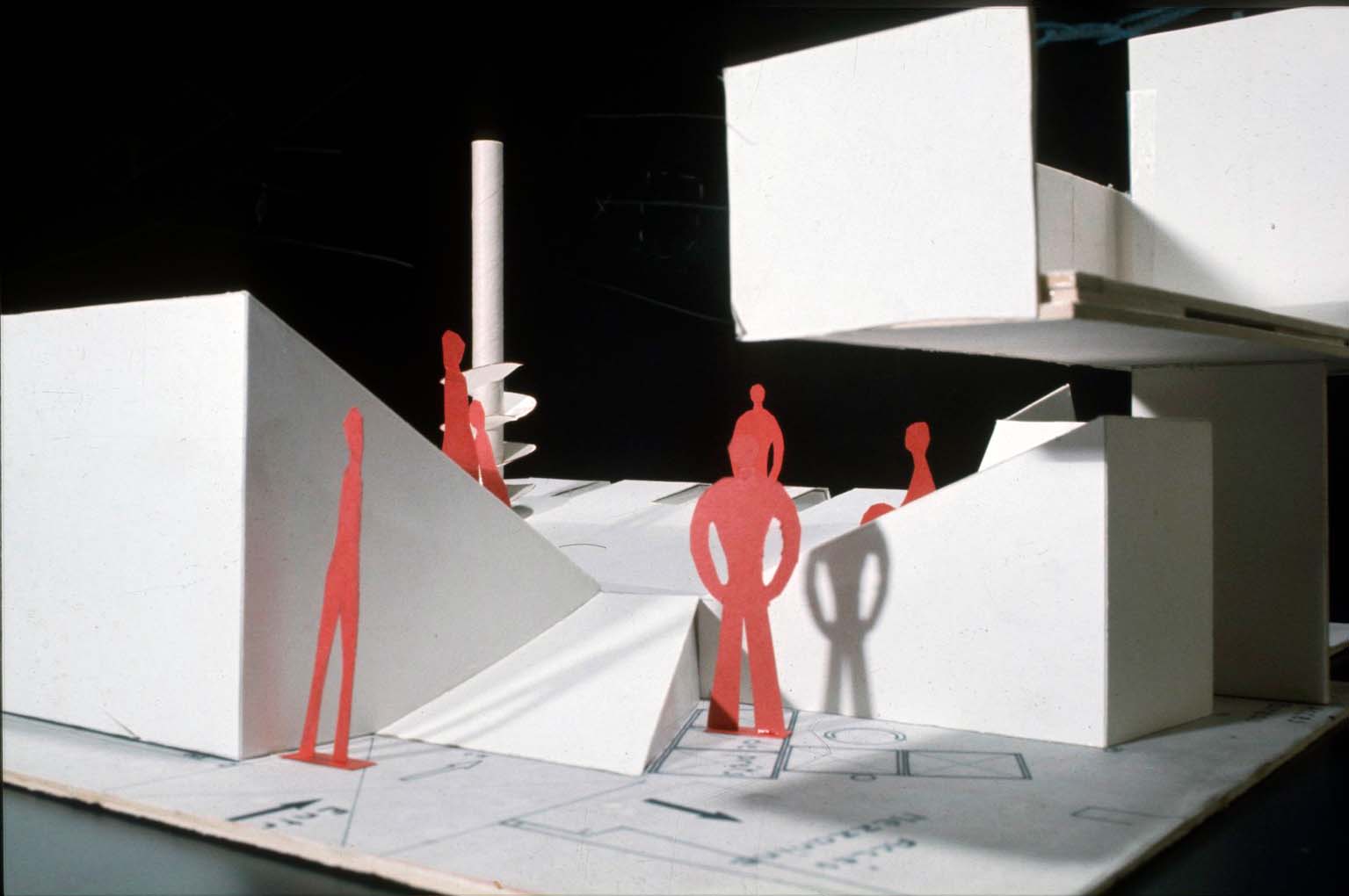

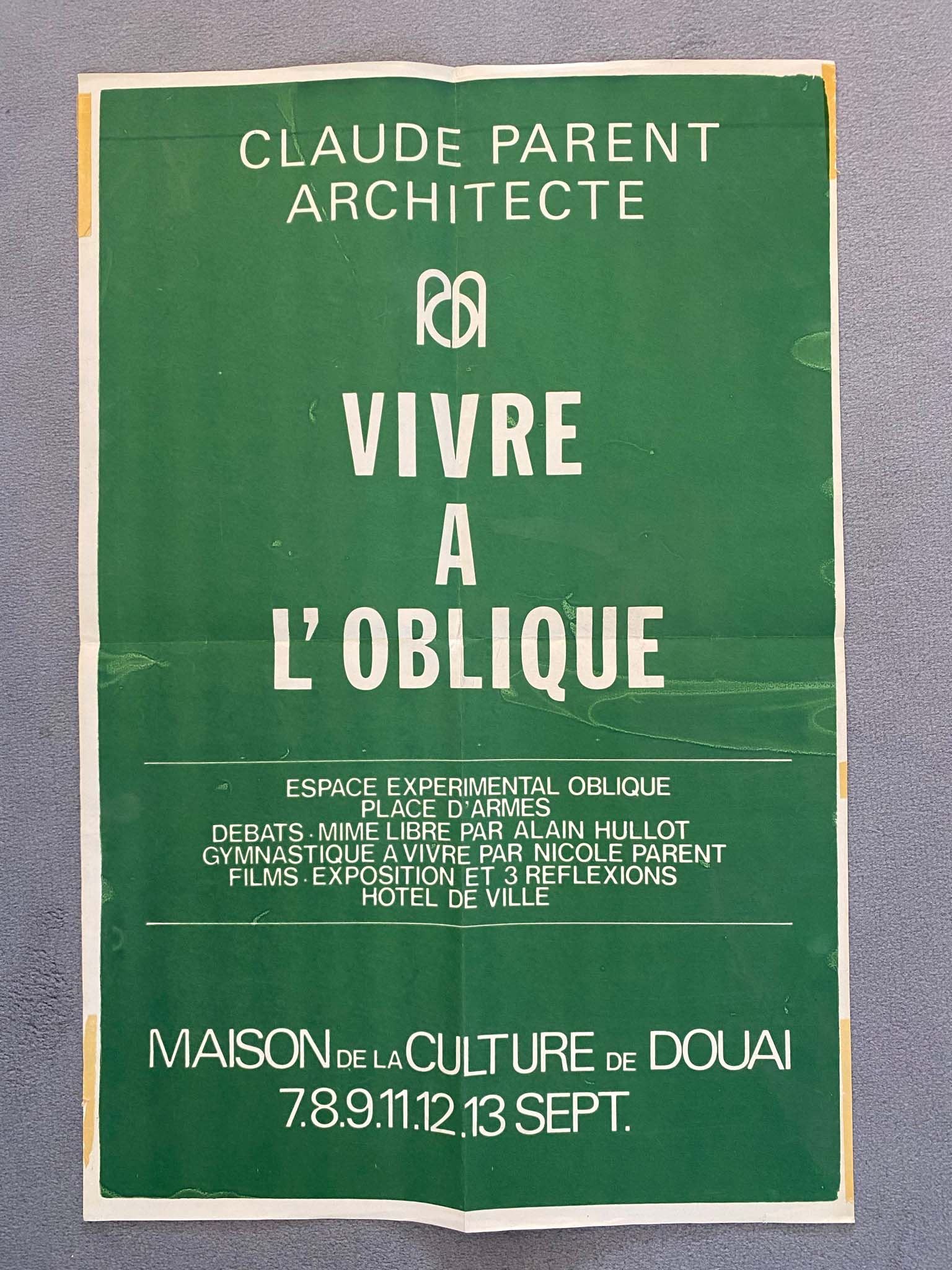

The prolific collaboration, however, came to an end as the turbulence of 1968 protests shook French society and the two men’s individual trajectories shifted away from one another. Virilio moved in a direction that eventually led him to the role of a prominent cultural theorist, while Parent remained committed to architectural practice through which he continued exploring various applications of the oblique function on his own. In the next few years following the dissolution of Architecture Principe, Parent traveled through France exhibiting his work and publicly lecturing about oblique architecture, designing along the way a series of temporary installations through which people could experience first hand what it was like to inhabit sloped floors.7 Among the oblique function’s principal ambitions was to use inclined planes not only for circulation—the way a ramp might—but rather as a substrate for most of life’s activities. Accordingly, these installations—known as practicables or, in French, praticables 8—sought to accommodate a combination of static and dynamic uses, from daily activities to special performances. This work took Parent to numerous cities all over the country— villes étapes or “stopover towns” as he called them 9—including Le Havre, Saint-Étienne, Rennes, Nevers, Toulouse, Reims, Amiens, Mâcon, Douai, Chalon-sur-Saône, and Caen. (Fig. 2.)

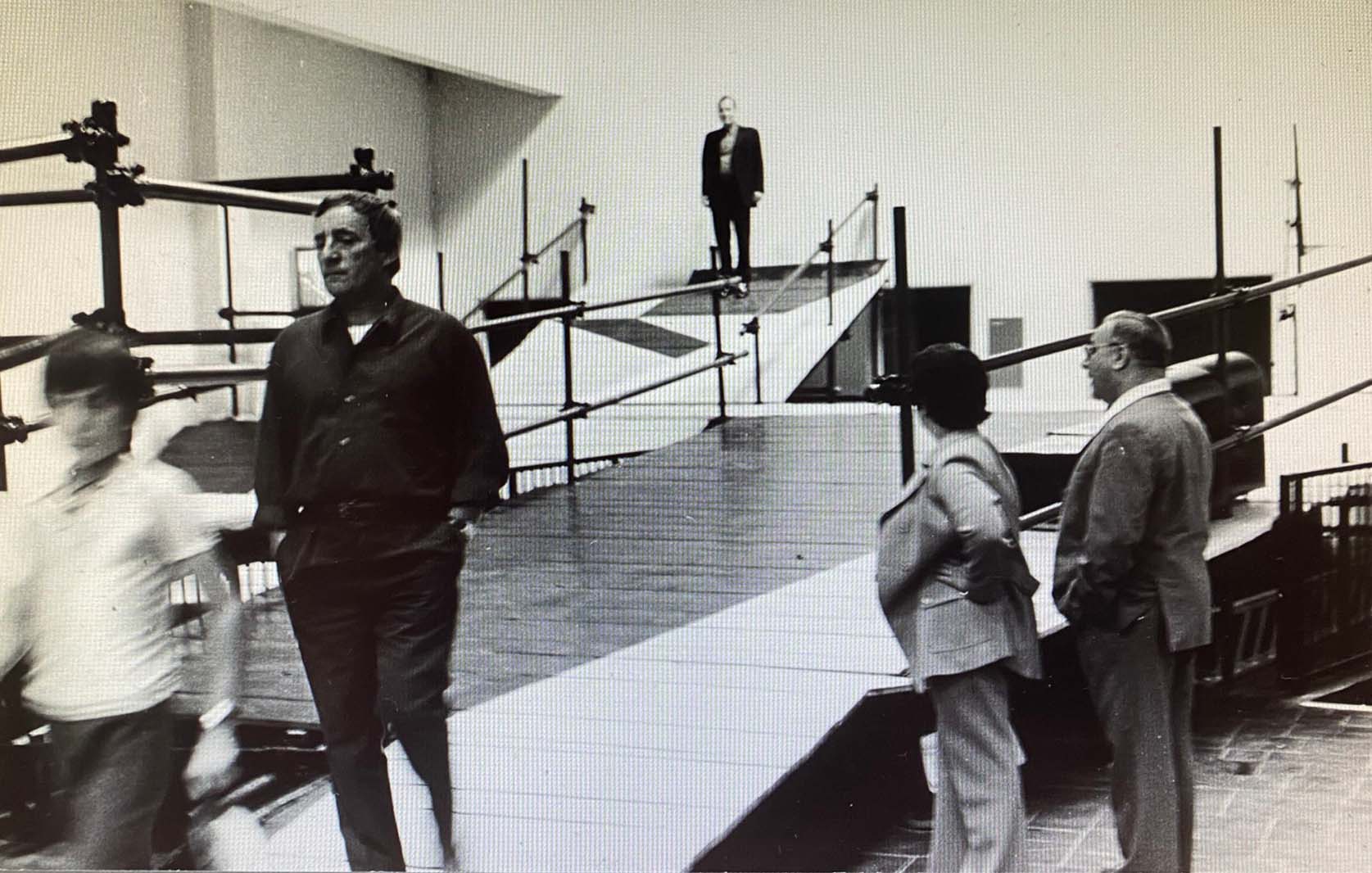

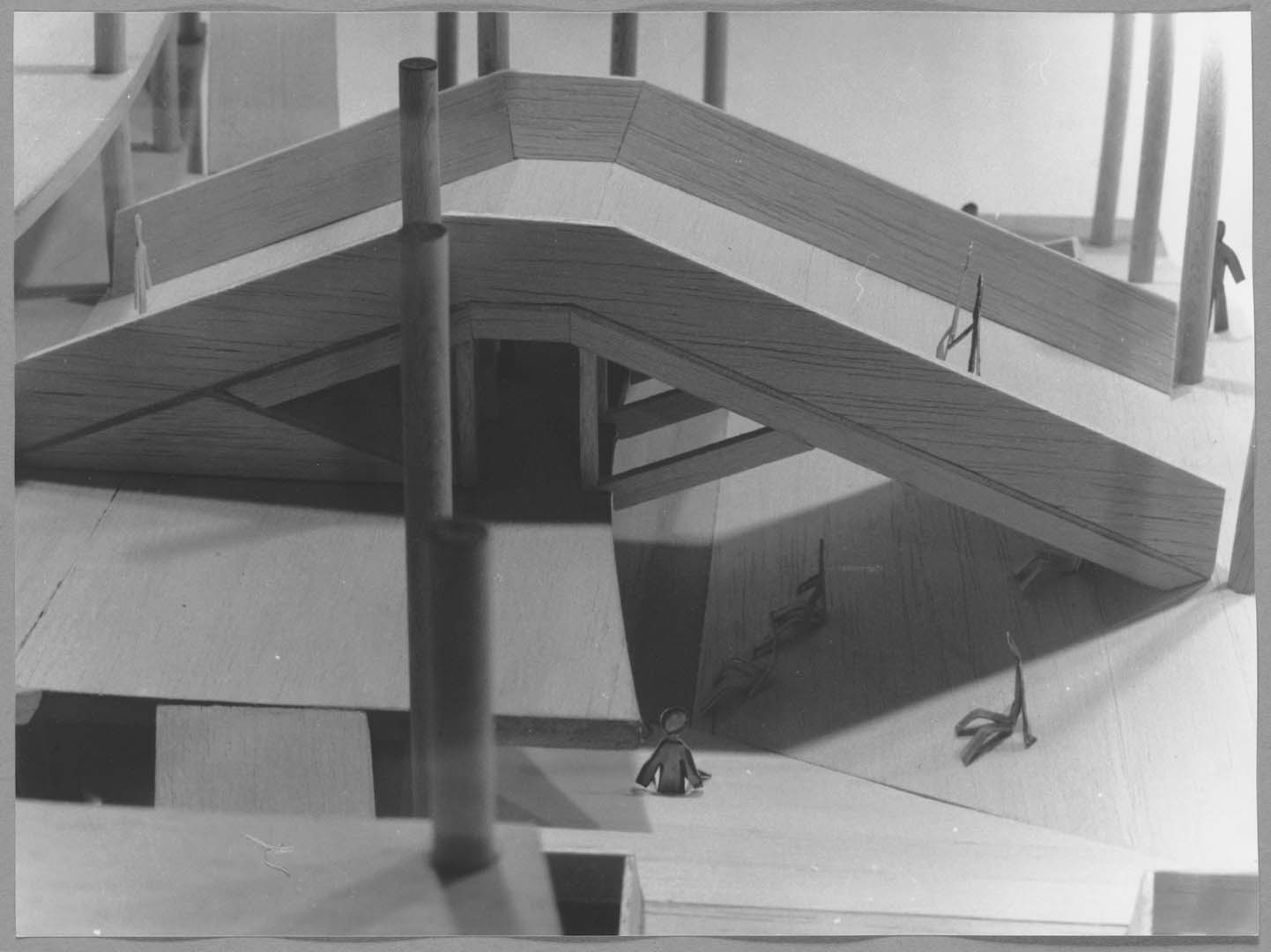

Each destination presented opportunities for engaging local organizations whose public programs served mostly popular audiences, while the exceptional extent of these efforts far exceeded the more typical repertoire of lectures and exhibitions by architects. In nearly every city the architect also tried, with various degrees of success, to build some form of a full-scale practicable. Compared to the provocative tone of the magazine Architecture Principe and the brutal presence of the concrete church, the practicable designs were, by comparison, unassuming. Made from modest materials and designed in response to the buildings that hosted them, they appeared informal as they were adaptive to each situation. A practicable was often no more than an assembly of repurposed scaffolding and painted wood planks. The installations at the Maison de la Culture de Nevers et de la Nièvre 10 (Fig. 3) and the Maison de la Culture d’Amiens exemplify such an economy of means and capture the ephemeral and seemingly improvised quality of these site-specific interventions set against the monumentality of the existing architecture. (Fig. 4.)

While practicables expanded upon Parent’s ongoing preoccupations with nonorthogonal geometries, this series of projects marked a shift in how he approached applying his theoretical ideas to practice. In the broadest sense, the change can be described as a movement toward a form of practice that prioritized social participation, that is, a way of developing architecture among and with people rather than only in an office or studio. Through such engagements, Parent was able to situate the oblique function socially in ways that exceeded his earlier attempts to do so through writing, drawing, and building. Rather than regarding Parent’s reorientation from the Architecture Principe-era avant-garde stance to the socially engaged nature of the tour as entirely willful, deliberate, or premeditated on the architect’s part, this article considers such a shift as a cumulative result of the alignments, opportunities, and constraints afforded by the public institutions that hosted and otherwise supported this work. The article as such examines the institutional context within which Parent’s peripatetic experiments took place as well as the government policies, social shifts, and cultural conditions that helped shape it. In other words, while Parent ambitiously set out to redesign the world according to the principles of the oblique function, nearly the opposite occurred, whereby it was the various aspects of his journey throughout provincial France—and thus the world well beyond his studio—that redefined his architectural practice. Situating Parent’s Tour de France in this way reveals a way of working that is intended to be of interest to contemporary architects and designers engaged in various experimental modes and practicing at a time when roles and limits of institutions, participatory practices, and public space continue to be in question worldwide.

THE TOUR OF FRANCE

In the spring of 1973, the popular magazine Le Point published a story titled “Le tour de France de Claude Parent,” describing the architect’s peripatetic programs as a process of establishing a dialog about architecture “between those who make it and those who live in it.” 11 At the time of the article’s publication Parent was working in Mâcon—a city 400 km [248.55 mi.] southeast of Paris with a population of approximately 30,000 inhabitants—where he mounted an exhibition; participated in a series of public workshops with local residents and public officials; staged live events, debates, and discussions with artists representing a variety of creative fields; and designed a sloped practicable to be implemented as part of the children’s reading room in the city’s newly constructed library. (Fig. 5.)

The combination of these engagements reflected the particular circumstances of the city in question, as was generally the case with each place he visited. Although his exhibitions and lectures repeated, to some extent, from one stop to another, the scope, format, and content of such programs changed considerably depending on the availability of resources as well as the needs and engagement of specific stakeholders.12 When reflecting upon this period decades later, Parent continued to refer to it as his “tour of France” and, as if speaking of a theater group or circus rather than an architecture studio, called the team he worked with “his troupe.” 13

The notion of a national tour as an exploratory journey also recalls the ongoing tradition of the Compagnons du Devoir et du Tour de France, an educational program for craftsmen and artisans who travel throughout the country for extended periods of time to apprentice with experts in their respective trades.14 Framed analogously, Parent’s tour can be regarded as just as valuable a learning experience for him as it was intended to be for the communities he visited along the way.

Parent’s tour effectively began in 1969 with an exhibition in Le Havre—featuring Architecture Principe’s work alongside Parent’s solo projects as well as the posthumous showing of his mentor André Bloc’s inhabitable sculptures 15—which was the first in the series of occasions for which Parent designed a practicable (Fig. 6). The large bridge-like structure rose up from the floor of the Nouveau Musée du Havre’s main gallery, a 1961 steel and glass building designed by architects Guy Lagneau, Michel Weil, and Jean Dimitrijevic, along with Jean Prouvé as a key collaborator.16 (Fig. 7.)

Parent placed the installation parallel to the gallery’s glass curtain wall facing the sea, juxtaposing in this way the practicable’s oblique profile with the flatness of the horizon in the background. The following year, Parent produced an oblique installation at the Venice Biennale, where he served in the capacity of the French Pavilion’s curator, bringing together a group of artists tasked with responding to the interior environment entirely made up of sloped floors. The Venice project integrated architecture, art, and public engagement in such a way that it became a prototype for his traveling programs in France, which continued until 1975.

In total, Parent visited more than a dozen cities, resulting in a total of five such constructions and various versions for at least four other unbuilt schemes, all accompanied by different combinations of talks, exhibitions, workshops, performances, and other types of live events. Among the practicable designs, most were sited inside existing buildings, although in Douai the installation was placed outdoors, while the Chalon-sur-Saône proposal provided a new circulatory path between the host venue’s exterior and interior spaces. Most were intended to be temporary, although some, such as the proposal for the theater in Caen, considered the practicable as a more permanent type of furnishing. The sum of these architectural devices, and the touring activities they were part of, is ultimately significant in contemporary terms not only for its role in extending theory toward application but also, with perhaps an ever more lasting impact, for modeling an expanded approach to the practice in architecture.

MALRAUX’S MAISONS DE LA CULTURE

Like the route of the cycling race to whose name it alluded, Parent’s itinerary was not a collection of arbitrary geographic destinations but instead reflected the underlying infrastructure that enabled it. In Parent’s case, it was a network of public institutions, primarily composed of maisons de la culture, that made his journey possible. Such institutions—also alternately referred to in this article as cultural centers or houses of culture—were tasked, starting in the late 1950s, with promoting visual and performing arts throughout France. The practicables built in Le Havre, Nevers, and Amiens, for example, were each sited inside of then newly constructed houses of culture, as was also the intention for the installations designed for Chalon-sur-Saône and Caen.17The sloped installation in Douai was also made possible by a collaboration with the city’s house of culture, but its unique outdoor siting—the only fully exterior practicable in the series, like an interior defined by its floor rather than walls—reflected the fact that as an organization the Maison de la Culture de Douai did not have its own building.18 (Fig. 8.) As cultural organizations and buildings, these cultural centers were the fiscal, social, and spatial infrastructure for Parent’s installations, and it was with their support that Parent was able to present architecture—and the oblique function—as the content, subject matter, and focus of their public programming. In effect, it was in the context of the houses of culture that Parent framed his theory of architecture as a form of popular culture taking up the domain of recreation and spare-time leisure.

The evolution of maisons de la culture as a building typology in France includes the establishment of institutions bearing that name as early as the 1930s, serving as intellectual and political grassroots centers known to have been frequented by some of the most avant-garde artists and architects of the time.19 The institutions with which Parent collaborated, however, emerged in a later era and are principally associated with the work of France’s first Minister of Cultural Affairs, André Malraux, appointed to the post by President Charles de Gaulle in 1959. Immediately after taking office, Malraux launched a statewide plan to establish new cultural centers all over France as a means of decentralizing and democratizing French culture.20 The rollout was intended to provide accessible cultural experiences across all of the country’s administrative regions, consistent with the government’s obligation to provide equal access to culture—in addition to education and professional training—to each citizen.21 The architectural program written for the construction of new houses of culture emphasized the need to support all forms of artistic expressions, including “those not yet imagined,” 22 resulting in the design of multiuse complexes and building configurations that sought to promote flexibility, versatility, and polyvalence.23 A typical complex included theaters, exhibition galleries, workshop spaces, a library, bar, or café, along with a room for emergent uses (Fig. 9).

Ultimately, the buildings’ purpose was to stage encounters with various forms of art in which the public could be both the audience and the producer. Visitors could, for example, attend a performance or be part of a local theater group; see an exhibition or take a photography class; and watch a movie or make one. Under one roof, such experiences were to provide a mixture of exposure to requisite cultural content and participation in artistic activities as a form of middle-class leisure.24 The purpose of Malraux’s policy was not only internal; the maisons de la culture were also envisioned as instruments for externally projecting France’s influence as the world’s most culturally developed nation.25

Malraux differentiated the role of the cultural centers from that of universities. While the academic institutions’ objective was the pursuit of knowledge and truth, the cultural centers had a different task. “Houses of culture don’t bring knowledge,” he said, “they bring emotion.” 26The cultural centers were thus administratively imagined as a system of public spaces imbued with emotion powerful enough to resonate globally, and this notion of feeling as opposed to thinking was incidentally not unlike Parent’s decision to disseminate his work through such venues rather than by following more conventional academic channels as many similarly experimental architects typically do.

The basis of Malraux’s top-down cultural initiative, part of the era’s overarching nation-building objectives, was not without conceptual and operational conflicts, among which was the dissonant relationship between geographic decentralization as an objective and Malraux’s ultimately “conservative definition of culture as artistic genius.” 27 In other words, an inclusive scheme in terms of geographic access collided with too exclusive of a conception of what counts as culture. Such rifts were at the core of the cultural centers’ pressure to evolve as institutions as the state program entered the second decade—post-1968—and as Parent set his tour into motion. In 1969, the year of Parent’s first realized practicable, Malraux concluded his decade-long term as minister. By then, the state program had executed the opening of several maisons de la culture housed in newly constructed buildings, while others occupied retrofitted existing buildings—and numerous additional centers were in various planning and design stages.28 Although the construction of new houses of culture continued selectively into the 1980s,29Parent’s tour of France unfolded during a particularly favorable, even if ultimately brief, period of their existence, enabling the kinds of public experiments that projected oblique architecture into everyday reality.

NEW TERRITORIES

The maisons de la culture’s geographic decentralization provided Parent with a national network of venues for disseminating his work beyond the rarified Parisian intellectual circles and the limited reach of avant-garde architecture press, which is where he was coming from.30 Circulating throughout provincial France, often in cities undergoing postwar reconstruction and accelerated rates of public housing development, allowed Parent to project the potential of oblique living onto a broader range of contexts which in turn seemingly brought his ambitions to put his theory into practice a step closer to realization. Rather than testing his ideas only on paper, Parent got to work within local communities which, in effect, served as his sounding board. As a self-proclaimed people-person, he was as eager to talk to his audience as to listen to them,31 even if being in this role was not without its challenges.32 If the oblique function were to make a difference in changing architecture and improving people’s relationship to it, Parent explained, he needed to find out whether there was a broad interest in what he imagined.33

Much like houses of culture “needed to attract everyone,” 34Parent’s programs also aspired to earn mainstream acceptance for his vision of life on inclined planes. Thus, Parent’s efforts to engage less urbanized parts of France cast a geographically wider net in search of a broader audience, while also reaching into regions experiencing a new wave of postwar development.35Such a departure from large urban centers like Paris can also be interpreted as the architect’s refusal to contribute to their further densification—according to the principles of the oblique function, vertical urban densification was as problematic as horizontal sprawl 36—as well as an embrace of peripheral territories where the construction of new types of settlements was still possible. In this context, the decentralized map of France, created by Malraux’s cultural policy, represented a new field or opportunity for putting things on a slant.37 Decades later, Parent admitted, “[W]e were lucky enough that André Malraux had launched maisons de la culture around that time!” 38

PROGRAMMATIC POLYVALENCE

Beyond their geography, it was the maisons de la culture’s mixed programmatic makeup that was particularly conducive to the development of Parent’s events and installations. The cultural centers’ hybrid role as part performance halls, part exhibition galleries, and part hobbyist art laboratories was echoed in the entanglement of different activities and presentation formats prepared by the architect, as if each built practicable were a scaled-down encapsulation of the larger host institution (Fig. 10).

The polyvalent programmatic agenda of maisons de la culture 39 or what the architectural historian Richard Klein calls “the beautiful idea of programmatic indetermination” 40 reflected the foundational administrative intention to have the buildings serve as enablers for all forms of artistic production—even those that have yet to emerge. Such an inclusive institutional framework was well suited to the presentation of architecture as an experimental art form.

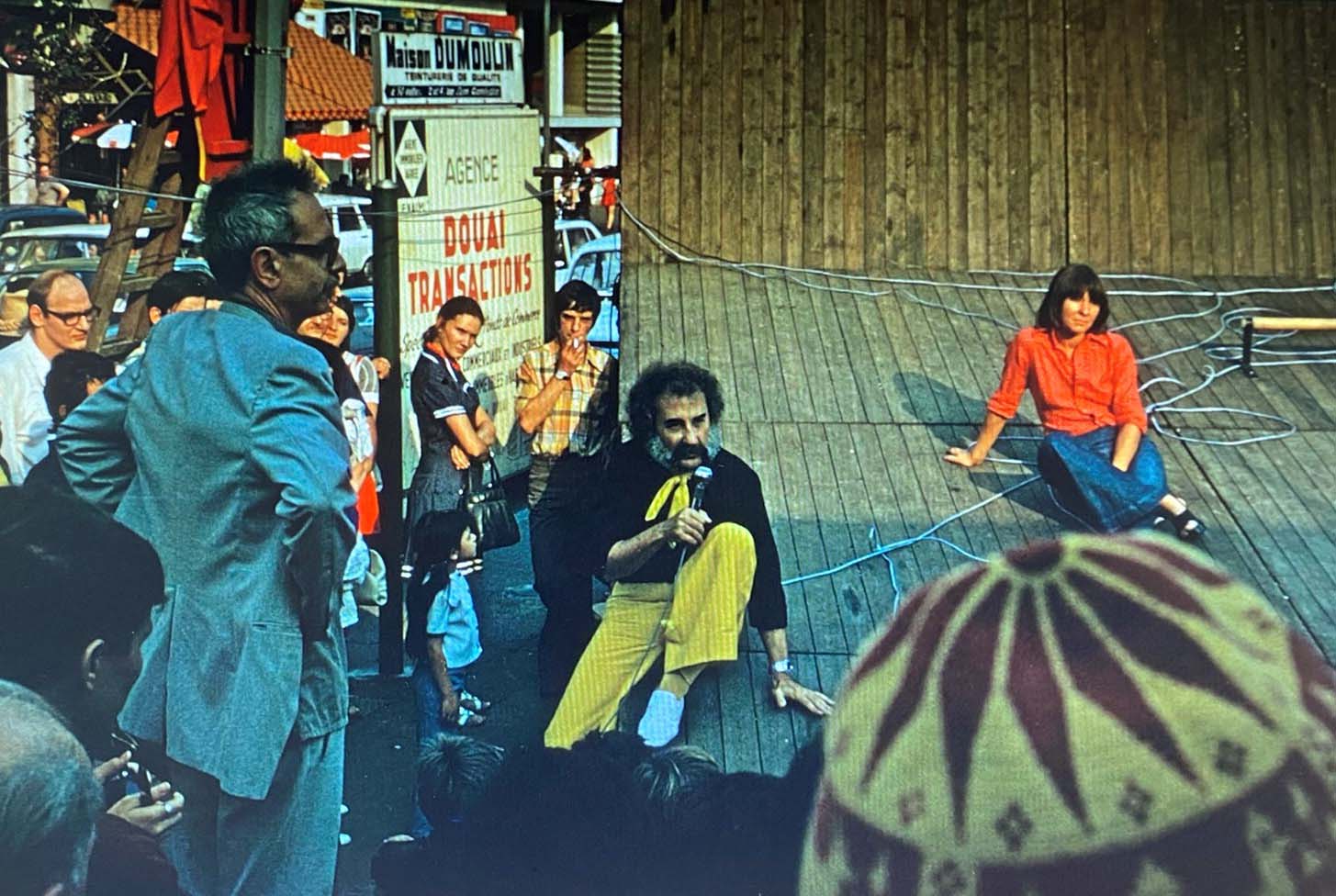

In general, houses of culture were already relatively open to the promotion of architecture through their public programs; an example of which was the posthumous exhibition on Le Corbusier presented as a part of the 1968 inauguration of the Maison de la Culture de Grenoble.41 Such programs provided an existing baseline for Parent’s exhibitions, lectures, and workshops, the experimental nature of which he pushed, more successfully in some cities than others, beyond conventional presentation formats. Incorporating aspects of live performance was particularly in line with the spirit of the cultural centers, whose theatrical inclination generally dominated the intended mixture of represented art forms that they housed. It was appropriate, given the context, that Parent’s practicables were designed as multifunctional stages where life and art could blend with one another. The architect in this way positioned architecture not as an object to be looked at, in the manner of fine art or conventional architecture exhibitions, but rather as a device that both enabled the transformation of audiences into performers and of performances blending with quotidian life.

This orientation toward theater—as well as Parent’s relationship to maisons de la culture more generally—was partially the result of the involvement of the writer and sculptor André Barey as the architect’s partner for major segments of the tour from 1971 onward. “A true one-man band, both impresario and actor,” writes the historian Audrey Jeanroy, “André Barey quickly became involved in the project, which he imagined as a living art show, close to experimental theater, based on the oblique function.” 42

Barey helped Parent network with the institutions and produce the programs based on his own experience and connections, having previously worked on establishing a cultural center in Orléans.43 Parent’s interest in closer collaboration with the public—as an architect with a reputation for utopian visions rendered in graphite and ink, more suited by convention to avant-garde salons than working-class community centers—was shaped by various factors, not the least of which was the ambition to find evidence in support of the oblique function as a hypothesis. In 5 réflexions sur l’architecture, for example, published as a result of his 1971 residency at the Maison de la Culture de Nevers et de la Nièvre,Parent explains that not unlike a scientific hypothesis, the oblique function required experiment-based evidence, particularly in relation to its psychological effect on its users.44 His architectural experiment, in other words, needed human subjects and thus, through interactive engagements with the public, his methodologies expanded beyond those that were already a part of the repertoire of conventional architecture practice.45

CULTURAL ACTION AND ANIMATION

While expanding the scope of Parent’s research toward public engagement may seem like an inevitable and self-driven step forward, such a move can also be interpreted as an opportunistic alignment with the evolving priorities of the maisons de la culture—and their municipalities—following the protests of 1968. At that time, the effectiveness of Malraux’s vision came into question, particularly in relation to the cultural centers’ actual reach within their communities,46 putting pressure on them to deliver a broader range of programs beyond those that conformed to the state’s existing criteria. Parent and Barey’s multifaceted productions, a blend of popular entertainment, interactive activities, and high-concept discourse (Fig. 11), effectively fulfilled the need for a broader appeal and deeper engagement with audiences least likely to set foot in such venues, aligning with what local and state administrations codified as actions culturelles and animations. These terms referred to public programs conceptualized during this era to encourage participation and expand the definition of culture in an effort to better engage local populations.47

In Mâcon, for example, instead of a maison de la culture, the municipality built a similar facility, but instead named it the Centre d’animation culturel. (The building opened in 1975; Parent’s programs in Mâcon took place during its construction, making use of different locations throughout the city instead of a single center.) That this was a change from the types of programs people already knew is captured in a local publication from November of 1968, in which residents of Mâcon could encounter the article titled “Cultural Action: Why?” Through a dozen bullet points, the socialist-governed municipality explained the purpose of actions culturelles. Listed among the aims, is collaboration among multiple organizations; creation of necessary conditions for “the power of leisure“ and entertainment; exploration of culture as “a perpetual means of liberation”; staging of first encounters between new artists and large crowds; links between past cultural heritage and contemporary forms of expression; opportunities for every resident to be heard; and the space for each person to “cultivate” themselves in their own authentic way.48 By promoting a compatible set of values, Parent’s programs in Mâcon, as well as other cities throughout the tour, tapped into a synergy between state and municipal ambitions to “activate” its citizens and the oblique function’s premise of the slope as a device for prompting active participation. In this way, Parent’s shift from conventional exhibitions and lectures to more socially interactive means of promoting his work during his period can be seen as a response to the changes in cultural policies devised by the organizations that supported him. As an architectural device designed to turn observers into actors, the practicable was thus also a product of such policy shifts.

CONSUMPTION AND PRODUCTION

If, as others have suggested, establishments like maisons de la culture were the state’s instruments for countering the evolving effects of postwar consumerism and mass production,49 then it is possible to identify another affinity that Parent shared with these institutions—his own disdain for the same types of prevailing societal tendencies. Throughout his career, the outspoken architect condemned the effects of mass production on architecture, the built environment, and modern life.50 The state’s apprehension about the alienating effects of mass consumption, mass media, and mass production, as expressed through the countering programmatic efforts of houses of culture and cultural actions, were in line with Parent’s views on mass-produced architecture. (Throughout his writing, individually and with Virilio, Parent associated orthogonal geometries in architecture with all that is mass produced, the alternative counterpoint to which was obliqueness.) The practicables can thus be seen as stages for countering consumerism, aligned with the cultural centers’ mandate to promote active participation rather than passive reception of the arts.51

In addition to serving as physical venues with favorable institutional dispositions, houses of culture also provided the material means for realizing Parent’s experiments, including money and labor. Like Architecture Principe’s magazine, Parent’s proof-of-concept tour certainly required self-initiative,52 not least of which was having to chase opportunities for public engagement as well as the funding to pay for it. At the time—though in many cases not for long thereafter—most of the maisons de la culture he worked with were still state-funded, including Le Havre, Nevers, Amiens, Douai, and Chalon-sur-Saône. State-sourced funds generally ensured not only better budgets for cultural projects but also required less dependence on box-office profit as was typically the case with locally run organizations, enabling greater degrees of experimentation and creative risk-taking. The cultural centers were staffed, providing Parent with the necessary labor to realize his plans—including the construction of the practicables (Fig. 12) —as well as access to local networks of businesses that made contributions in the form of various types of donations and sponsorships.53 In addition to staging live programs, collaborating with houses of culture also yielded a range of printed artifacts—such as newsletters, leaflets, pamphlets, posters, as well as entire books (Fig. 13)—in ways that exceeded the limitations of self-financed publishing of the manifesto-magazine a few years earlier.54

While it lasted for only a few years, such financial and creative support sustained Parent’s public explorations of the oblique function and resulted in robust programs of which those produced for the Maison de la Culture d’Amiens from late 1972 to early 1973 are the best example. In addition to the prominently sited practicable, visible from the outside through the oversized glazed openings of Pierre Sonrel-designed building façade (Fig. 14), a robust rollout of programs captured the overarching intention of these productions. It included exhibitions of not only Parent’s architectural portfolio but also paintings by the Chilean artist Roberto Matta and Parent’s frequent collaborator Andrée Bellaguet; various musical performances, discussions, as well as extensive printed matter promoting the architect and the many events on and around the practicable. Once funding cuts started to occur along with shifting state policies and municipal priorities,55 Parent’s practicabledesigns were also no longer getting built, and eventually his tour came to its conclusion.56 (Fig. 15.) The end coincided with the state’s diminishing commitment to Malraux-era policies, validated by a damning report from 1976 which disclosed the cultural program’s ineffectiveness in meeting its initial objectives.57 By then, Parent had yet again started pivoting his practice toward other prospects.

CONCLUSION

Situated in the broader context, the development of Parent’s tour of France, and the design of the practicables, can be traced in relation to the evolution of houses of culture as public institutions. Such consideration reveals the synergies between the institutional interests of the maisons de la culture and the architect’s professional and artistic ambitions at that time.58 Explorations of oblique living shaped the cultural centers’ public programs, while their social and administrative agendas—as well as the very architecture of their facilities—provided a new framework for Parent’s practice. Programmatic uses of the practicables, as well as various factors related to the realization of each installation—not least of which is that some of the proposed schemes did not get built—were the result of the particular circumstances encountered in each city, capturing in effect the site-specific nature of the entire architectural tour. Ultimately, while the architect’s long-term impact on the places he visited may have been limited, the sum of these touring experiences, on the contrary, profoundly shaped not only Parent’s work during this period but also his broader perspective on practice. In particular, the experience of working directly with people appears to have changed his attitude about the nature of architectural experiments.59

Reflecting upon his travels in support of the oblique function in a memoir published in 1975—zeroing in on his work in Amiens, which he considered to be the tour’s greatest success—Parent writes about the power of direct physical engagement with the constructed slopes as it unfolded in these public productions, while also recognizing the need for accountability when it comes to experimenting with people’s living environment. Radical changes to architecture and its potential behavioral impact, he writes, require “repeated experimentation over a long period time, with care and through provisional actions.” 60 The status of the practicables as experimental instruments was thus meant to be, to echo Parent and use the French word fugitive—fleeting or ephemeral—rather than fixed, much like the live programs that accompanied them. He further writes, “In architecture, at a certain level, you can’t play with people according to your own ideas, even if you have the best of intentions.” 61

The tour was thus not only a journey through France but also a profound leap in the overall trajectory of the oblique function, from a provocation and an avant-garde gesture of the Architecture Principe period to a hypothesis in need of evidence with which the tour started to, finally, a provisional participatory methodology that prioritized personal perspectives of its subjects over the autonomy of architectural form. Tracing this trajectory from form to participation may also be useful when drawing connections between Parent’s overall body of work and contemporary architecture. Such an exercise may help us get beyond reiterating the architect’s legacy as an exceptional figure in French architecture or prioritizing the undeniably innovative and influential formal aspects of his work as has already been done by various scholars, curators, and other architects. It may also help us get past the idiosyncratic obsessions with slanted floors in order to access other potential aspects of architecture as an oblique social practice.

The group’s formation, and the development of the oblique function, has been recounted on numerous occasions by Parent and Virilio, as well as architecture scholars. See Paul Virilio, “Architecture Principe,” in The Function of the Oblique: The Architecture of Claude Parent and Paul Virilio, 1963–1969, ed. Pamela Johnston(London: AA Publications, 1996), 11–13; see also Audrey Jeanroy, Claude Parent: Les dessins d’un architecte (Marseille, Fr.: Parenthèses, 2022), Chapters 4 and 5.

The monograph The Function of the Oblique: The Architecture of Claude Parent and Paul Virilio, 1963–1969 provides an overview of this body of work and is one of the few book-length publications about Architecture Principe published in the English language. A comprehensive overview of the group’s output, part of a survey of Parent’s lifelong practice, is also included in the monograph accompanying the 2010 exhibition Claude Parent: l’œuvre construite, l’œuvre graphique; see Frédéric Migayrou, ed., Claude Parent: l’œuvre construite, l’œuvre graphique (Paris: Éditions HYX, 2010).

Jacques Lucan, “Introduction,” in Johnston, The Function of the Oblique, 5.

Paul Virilio, “Avertissement,” Architecture Principe no. 1 (February 1966): 2. See the English translation in Paul Virilio and Claude Parent, Architecture Principe 1966 and 1996, trans. George Collins (Besançon, Fr.: Les Éditions de l’Imprimeur, 1997), III.

The nine issues of the magazine, originally published throughout 1966, were eventually collected into a single volume and subsequently translated to other languages, including English. See Paul Virilio and Claude Parent, Architecture Principe 1966 and 1996, trans. George Collins (Besançon, Fr.: Les Éditions de l’Imprimeur, 1997).

The extensively published project is also subject of a monograph entirely dedicated to it. See Frédéric Migayrou, ed., Nevers: Architecture Principe—Claude Parent Paul Virilio (Paris: Éditions HYX, 2010).

During this period immediately following his collaboration with Virilio, Parent also wrote and published another text concerning oblique architecture, the book Vivre à l’oblique, as an updated version of ideas initially conceived through the work of Architecture Principe. See Claude Parent, Vivre à l’oblique (Paris: self-published, 1970). This text, with a title that translates to English as “Oblique Living,” in effect became a key theoretical reference in Parent’s practice during this period.

In French, the word praticable stands for a floor or platform on which an activity occurs, such as a theatrical performance or gymnastic exercise. As a matter of décor or scenography, a praticable is also an element that exists three-dimensionally rather than being painted on or represented through a flat image. The adjective form of the word references something passable—like a path—or, in another sense, something that is possible to put into practice, as in feasible or achievable. The equivalent English term used to describe theatrical props and scenery is “practicable,” although the adjective’s abbreviated version, “practical,” is more common today. See Martin Harrison, The Language of Theatre (New York: Routledge, 1998), 203–204. In the book Practicable: From Participation to Interaction in Contemporary Art, the adjective “practicable” qualifies works of art that are actualized by practice, while its editors also acknowledge the usefulness of the noun form, as it exists in French, “insofar as the practicable is a potential site of action or performance.” See Samuel Bianchini and Erik Verhagen, eds., “Introduction: Practicable—Art in the Conditional,” in Practicable: From Participation to Interaction in Contemporary Art (Cambridge MA, USA: MIT Press, 2016), 14.

Josiane Marié, “La fonction oblique en voyage,” Le Journal de la Maison, March 1974, 171.

Maison de la Culture Nevers et de la Nièvre, later renamed Maison de la culture Nevers Agglomération (MCNA), was part of a larger multiuse complex, also consisting of Maison du travail and la Maison des sports, inaugurated in 1970. It was designed by the architects Max Guillaume and Henri Veuzelle, with the designer Camille Demangeat. See Richard Klein, Les maisons de la culture en France (Paris: Éditions du patrimoine, Centre des monuments nationaux, 2017), 40.

Hélène Demoriane, “Le tour de France de Claude Parent,” Le Point, March 19, 1973, 58–59; my translation.

Parent noted the difference between fixed exhibitions and ephemeral events that accompanied them. He says, “Such a live event is not fixed and rigid like an exhibition. Its form is determined by the nature of the host structures, their resources, and their contacts with the public. It’s never the same!” In “La fonction oblique en voyage,” 171. My translation.

Abu ElDahab and Benjamin Sorer, Oblique Time with Claude Parent (Berlin: Bom Dia Books, 2019), 78.

“Compagnons du Devoir et du Tour de France” – https://compagnons-du-devoir.com/, accessed May 2, 2024.

This was among the last public endeavors that Parent and Virilio pursued together as Architecture Principe, not counting their various reunions in the 1990s. André Bloc was an artist, engineer, and founding editor of the influential magazine L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui. He was Parent’s mentor and collaborator starting in the early 1950s until his sudden death in 1966. The exhibition in Le Havre, titled Espace Architectural, was in this way Parent’s final collaboration with two men—Virilio and Bloc—both of whom had a tremendous impact on his development as an architect.

The building, originally called Musée-maison de la culture du Havre, was the first French cultural center to open following AndréMalraux’s 1959 establishment of the state program under which such institutions were to be built all over France. It was originally designed as a museum, but subsequently opened to the public, in 1961, in its modified and expanded role. See Richard Klein, Les maisons de la culture en France (Paris: Éditions du patrimoine, Centre des monuments nationaux, 2017), 36. By 1969, the year Parent did his exhibition there, the building became primarily a museum once again and was renamed the Nouveau Musée du Havre, while the operations of the cultural center moved to the Théâtre de l’Hôtel de Ville. See “Découvrez le MuMa: une histoire,” Musée d’art moderne André Malraux – https://www.muma-lehavre.fr/fr/musee/muma/une-histoire, accessed May 22, 2023. The maison de la culture was nonetheless one of the institutional partners responsible for the production and presentation of the 1969 exhibition as reflected in accompanying pamphlets, posters, and local press. In 1999, the museum was renamed after André Malraux.

Given the ultimately complex evolution of these establishments, some of the buildings that were used as sites for the practicables had changed their status and modified their name by the time Parent arrived there. In Le Havre, as already noted, the maison de la culture had become a museum even though the city’s house of culture still acted as co-presenter of his exhibition. In Caen, where the establishment of the state-funded maison de la culture involved a contentious relationship with the municipality, the cultural center was eventually renamed Théâtre municipal de Caen as its management shifted from state to local administration.

The Maison de la Culture de Douai had a space for its operations at the city hall, located in the town’s historic center a block away from the practicable’s outdoor site.

Danilo Udovicki-Selb, for example, writes about the convergence of political and artistic activities in the 1930s maisons de la culture in the life and work of Charlotte Perriand. See Danilo Udovicki-Selb, “ ‘C’était dans l’air du temps’: Charlotte Perriand and the Popular Front,” in Charlotte Perriand: An Art of Living, ed. Mary McLeod (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2003), 68–89.

Richard Klein, Les maisons de la culture en France (Paris: Éditions du patrimoine, Centre des monuments nationaux, 2017), 34.

The policy was in place since the adoption of the 1946 preamble to the French constitution, See Le préambule de la constitution du 27 octobre 1946. “A Nation garantit l’égal accès de l’enfant et de l’adulte à l’instruction, à la formation professionnelle et à la culture.” [The Nation guarantees equal access for children and adults to instruction, vocational training and culture.] – https://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/en/preamble-to-the-constitution-o....

Klein, Les maisons de la culture, 38.

Kenny Cupers, “The Cultural Center: Architecture as Cultural Policy in Postwar Europe,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 74, no. 4 (December 2015): 470.

Cupers explains, “Cultural institutions—went the argument, especially on the political Left—should become sites of participatory production and not just passive consumption.” Cupers, “The Cultural Center,” 469.

Klein, Les maisons de la culture, 34.

Malraux’ speech, given at an art festival in Dakar, is quoted in Éric Lengereau, “Malraux ministre de l’architecture,” in André Malraux et l’architecture, ed. Dominique Hervier (Paris: Éditions du Moniteur, 2008), 83.

Kenny Cupers, The Social Project: Housing Postwar France (Minneapolis MN, USA: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 119.

Klein, Les maisons de la culture, 42.

For example, the architect Oscar Niemeyer’s building in Le Havre, the city’s second maison de la culture, opened to the public in 1982; Mario Botta’s design for the center in Chambéry, named after Malraux, was completed in 1987.

Audrey Jeanroy, “Pratiquez l’architecture!: Les actions culturelles de Claude Parent, 1969–1975,” in Migayrou, Claude Parent, 166.

Abu ElDahab and Benjamin Sorer, Oblique Time with Claude Parent, 78.

In his memoir from 1975, Parent wrote about various challenges along the tour, such as occasions in which he was unknowingly pushed by local organizers into encounters with people who were more eager to discuss their grievances concerning the city’s administration than exploring architecture. See Claude Parent, Architecte: un homme et son métier (Paris: Éditions Robert Laffont, 1975), 176–177.

See, for example, Claude Parent, 5 reflexions sur l’architecture (Nevers, Fr.: Maison de la Culture de Nevers), 39–42.

Cupers, “The Cultural Center,” 470.

Cities like Le Havre, Amiens, and Caen were destroyed by Allied bombing and became major sites of reconstruction; other cities were in the process of building new public housing on their outskirts. such as the Gautriats neighborhood in Mâcon where Parent worked with the residents.

Paul Virilio, “Le troisieme ordre urbain,” Architecture Principe no. 2 (March 1966): 9. See the English translation in Paul Virilio and Claude Parent, Architecture Principe 1966 and 1996, trans. George Collins (Besançon, Fr.: Les Éditions de l’Imprimeur, 1997), VIII.

While the tour was his primary activity during this period, his practice continued through other pursuits as well. At the start of the tour, he designed shopping centers for similarly provincial sites, one example of which is located in Sens, in rural France. In these commissions too, Parent explored oblique geometries and circulation.

ElDahab and Sorer, Oblique Time, 140.

Polyvalence simply means having the possibility of using given spaces in different ways. See Cupers, “The Cultural Center,” 470.

Klein, Les maisons de la culture en France, 51.

Richard Klein, “Des maisons du peuple aux maisons de la culture,” in André Malraux et l’architecture, ed. Dominique Hervier (Paris: Éditions du Moniteur, 2008), 121.

Jeanroy, “Pratiquez l’architecture!” 166. While according to Jeanroy’s account, Parent and Barey’s initial encounter took place in Venice during the 1970 Biennale, an alternate account exists as well. Parent recounts, “Director of the Maison de la Culture, Mr. Philippe Bonzon, sent one of his delegates, Mr. André Barey, to Saint-Étienne, and on his advice, we put together an event.” See Josiane Marié, “La fonction oblique en voyage,” 171; my translation. Following the chronology of either account, Barey’s involvement started after 1970; Parent’s exhibition in Saint-Étienne was in 1971, as was his visit to Nevers, where he built the first practicable after Venice.

See the biographical note in André Barey, Réflexions sur l’artisanat, suivi d’une intervention de Claude Parent (Mâcon, Fr.: Action culturelle mâconnaise, 1973). From various local press coverage and publications promoting these local events, it is evident that Barey was instrumental in linking Parent’s practice with the cultural center’s cultural programs. In other words, it was thanks to Barey that Parent’s work was presented as a form of participatory practice in these venues.

Parent, 5 réflexions sur l’architecture, 39–40.

It is important to note that while Parent compares his process with a scientific experiment—and during various stages of this exploration he invited a number of physicians, psychologists, and sociologists to join him—this methodology is to not be confused with evidence-based research that emerged in the mid-twentieth century that continues to be a part of various design fields today or that sets up the expectation for the administration of data collecting. For Parent, the question of methodology was still open. As he later wrote, throughout the tour he was seeking direct feedback as much as he was still in search of a methodology. Claude Parent, Architecte: un homme et son métier (Paris: Éditions Robert Laffont, 1975), 185.

In this context, the following criticism was made by the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, as cited by Klein, “Most popular education undertakings, and in particular the maisons de la culture, are inspired by an ideology which, despite the variants and variations, is organized around a common accepted idea and which body of most often appears to be the systematic expression of a certain type of social situation. As if believed that the mere physical inaccessibility of the works prevents the great majority from approaching, contemplating and enjoying them, those in charge and the organizers seem to think that all that is needed is to get the works to the people, since they cannot get the people to come to the works.” See Klein, Les maisons de la culture en France, 42; my translation.

This is especially true in cities that experienced a large increase of new public housing; in such areas, the “animations” were a part of a sociological strategy for managing new communities. See in: Kenny Cupers, “Animation to the Rescue,” chap. 3 in The Social Project: Housing Postwar France, 95–136.

“L’action culturelle: pourqoui?” Mâcon: Revue Municipale no. 2 (November 1968): 23.

Cupers, The Social Project, 122.

For examples, see Claude Parent, “Préfabrication,” Architecture Principe no. 2 (March 1966): 7. See the English translation in Architecture Principe 1966 and 1996, XXII; see also Claude Parent, “Face à face: architecture et design,” L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui no. 155 (April–May 1971): 19–23.

Broader engagement with questions of consumption and consumerism in France and internationally appeared in the work of many of Parent’s contemporaries across a range of disciplines, particularly sociology, including that of Pierre Bourdieu whose research directly addressed the role of institutions such as the maisons de la culture. Jean Baudrillard’s book The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures was also published in 1970 (Paris: éditions Denoël).

ElDahab and Sorer, Oblique Time, 78.

In Nevers, for example, it was the house of culture technical crew that constructed the practicable; in Amiens, a local construction firm; the planned practicable in Caen was supposed to be built by a contractor from Rouen; in Le Havre, it was a plywood company’s material donation that made the construction of the installation possible.

This includes the publication of books in Nevers, Mâcon, as well as numerous essays published in newsletters. Amiens, for example, was particularly well funded.

Cupers, “The Cultural Center,” 472.

ElDahab and Sorer, Oblique Time, 78.

Klein, Les maisons de la culture, 43.

Jeanroy, “Pratiquez l’architecture!” 168.

The very term “experimental architecture” was codified around the same time as the start of Parent’s tour, principally through the publication of Pater Cook’s 1970 book Experimental Architecture. While neither Parent nor Architecture Principe were included in the book—while other architects practicing in France, such as Yona Friedman, Jean Prouvé, and the group Utopie were—Parent was engaged with Cook and Archigram on multiple occasions, including exhibitions, symposia, and publications. It is possible to see Parent’s reflection on the nature of experimental architecture as informed by, or perhaps even a response to, the discussions on the subject that were in circulation at that time. See Peter Cook, Experimental Architecture (New York: Universe Books, 1970).

Parent, Architecte, 183; my translation unless noted otherwise.

Parent, Architecte, 183.

Special thanks to Chloé Parent, Laszlo Parent, and the Claude Parent Archives, Paris for providing access to research materials and permission to publish them, as well as for their continued support of this project.

Figures 1, 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 13: images by © the Author.

Figures 3, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 15: © CNAC/MNAM, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY; Bibliothèque Kandinsky/Musée National d’Art Moderne/Centre Pompidou/Paris/France.

Igor Siddiqui is an Associate Professor at the University of Texas at Austin where he holds the Gene Edward Mikeska Endowed Chair in Design. He is a registered Architect, Design Scholar, and Educator. Through a combination of teaching, writing, and creative practice, his work explores the convergence of public engagement and design experimentation. He earned his Master of Architecture at Yale University. E-mail: igor.siddiqui@utexas.edu.